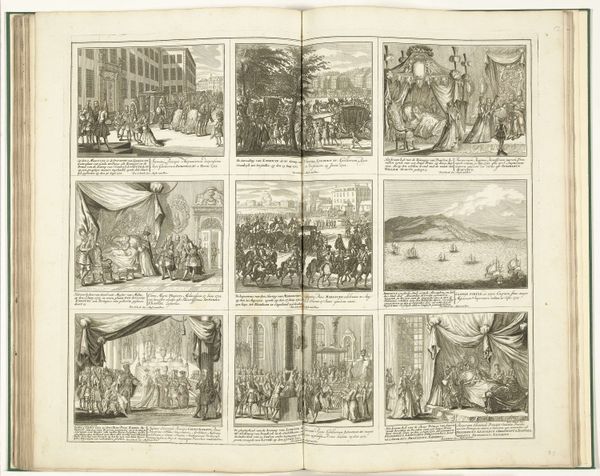

print, engraving

#

narrative-art

#

baroque

# print

#

history-painting

#

engraving

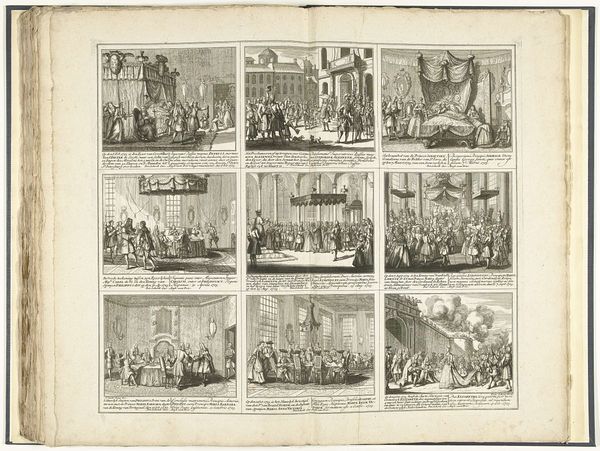

Dimensions: height 538 mm, width 635 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

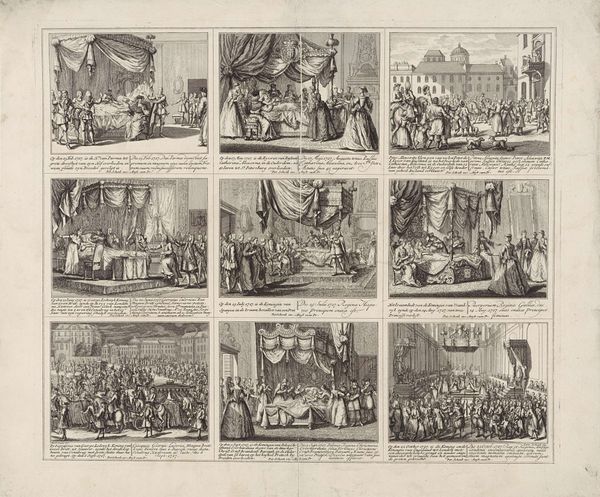

Curator: "Schouwburg van den oorlog (blad XXI)", or "Theatre of War, sheet XXI," created by Leonard Schenk around 1720. It’s an engraving, currently held in the Rijksmuseum. Quite detailed for its size. Editor: It feels… compressed. Nine separate scenes vying for attention on one page, a barrage of tiny figures frozen in baroque drama. The stark black and white emphasizes the conflict. Curator: That compression reflects the historical lens, I think. Each scene encapsulates a key event – treaties being signed, battles being fought, sieges laid – reduced to symbolic tableaux within this theater of war. Note the recurrent motif of figures posed beneath canopies, signs of authority. Editor: Precisely, look at how repetitive the scenery becomes. Aren’t all these royal gestures being rendered assembly-line style by similar techniques? Think of the workshop churning these out. Mass communication, but filtered through established aesthetic tropes of power. Curator: Yet each image also functions as a microcosm, reflecting larger ideological tensions of the era. For instance, consider the naval battle; the ship acts as a symbol of mercantile power, expansion, and control, anxieties palpable even now. Editor: It raises an interesting question, though, of the print as a commodity. Does the reproducibility dilute the original symbolic intention? Or does it amplify it, allowing access to these images to a wider, and potentially more critical, audience? This isn't just about monarchs; this image gets distributed through print shops. Curator: A vital question. Print democratizes access, undeniably. But the images still communicate encoded cultural scripts - heroic leaders, the brutality of war justified. A double edged material presence. Editor: Exactly. So even within mass production, we must ask what these recurring representations of violence normalize, the type of labour going in this endeavor. Curator: True enough. It all speaks to the enduring power, and potential manipulation, of images as historical tools, then and now. It offers a lesson about how conflicts and the systems maintaining those can spread through an economy of making and symbolism. Editor: So, we might consider this engraving not just a theatre of war, but a stage for analyzing power and the conditions that make this spectacle possible, while recognizing ourselves inside of that making process too.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.