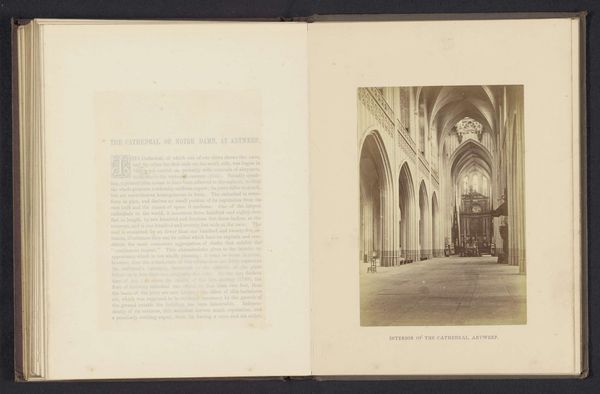

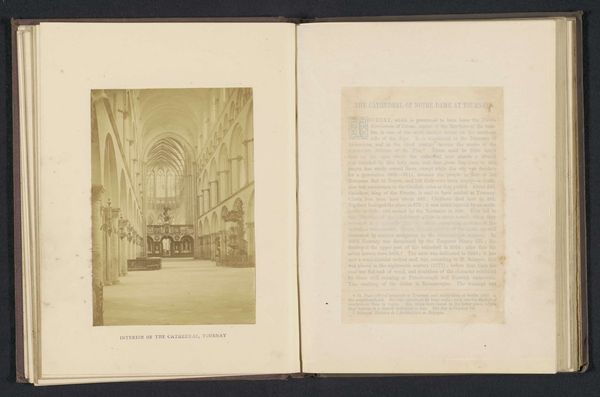

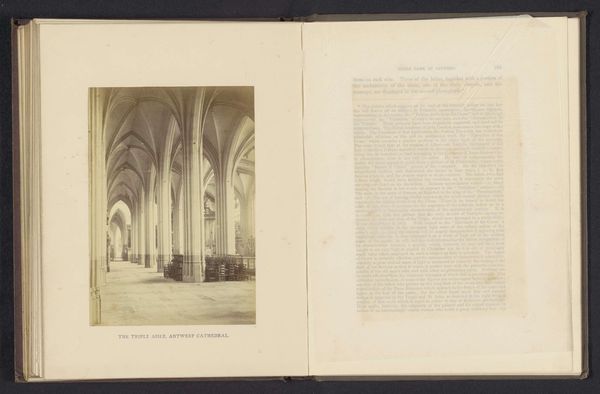

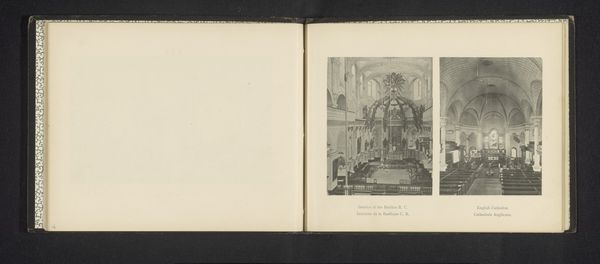

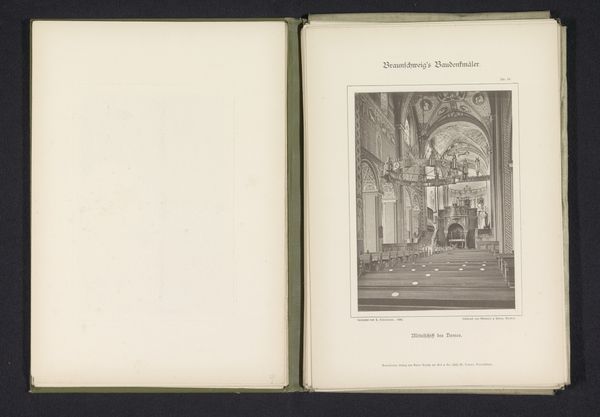

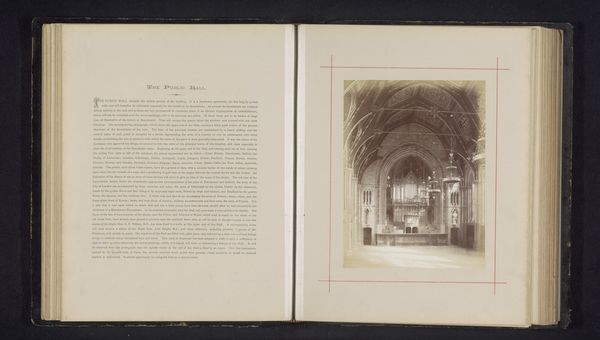

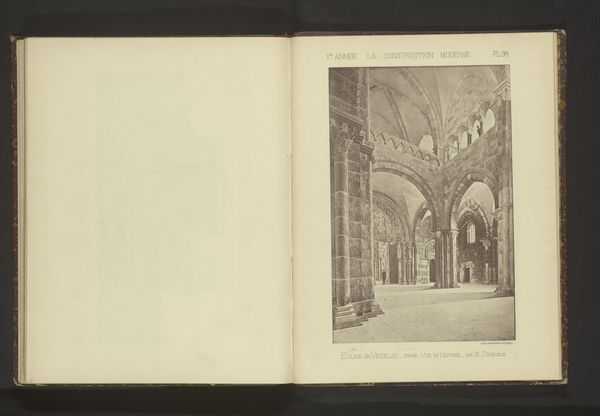

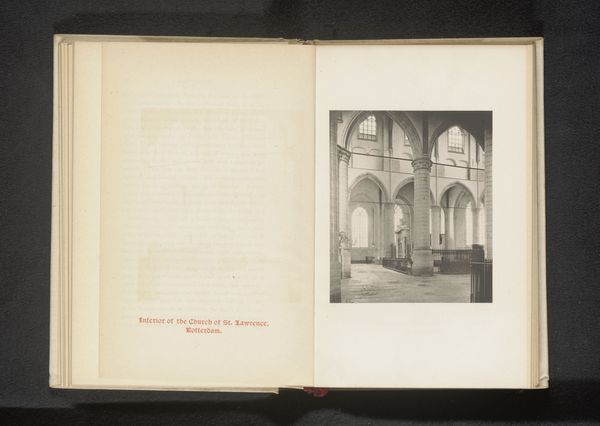

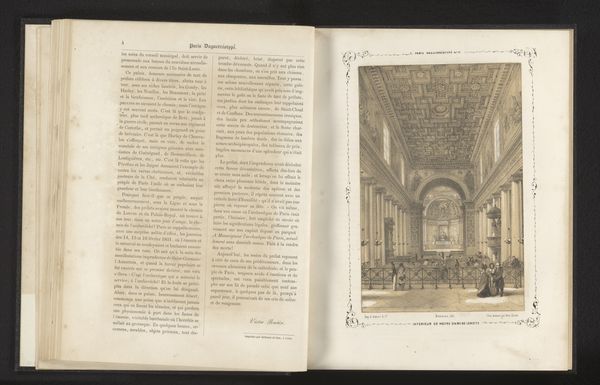

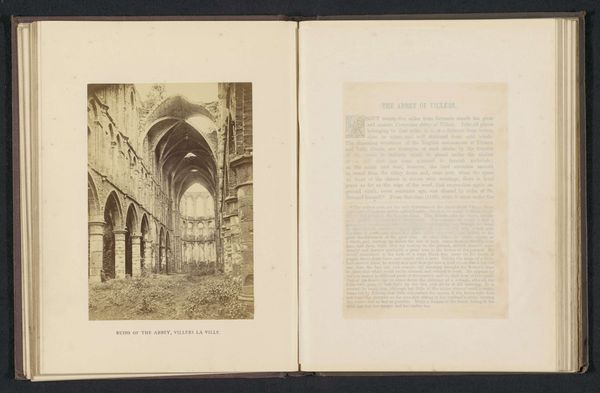

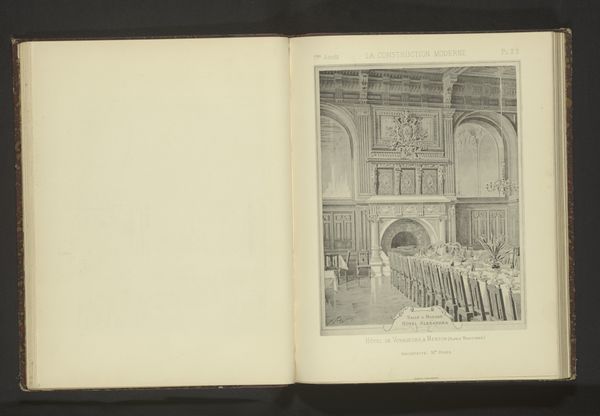

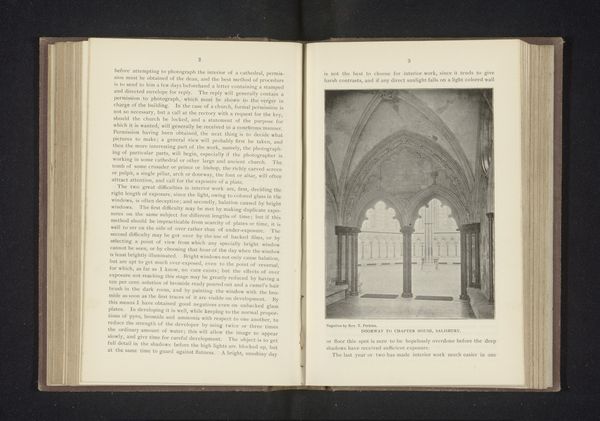

print, photography, gelatin-silver-print, architecture

#

aged paper

#

script typography

# print

#

hand drawn type

#

landscape

#

photography

#

personal sketchbook

#

hand-drawn typeface

#

fading type

#

stylized text

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

thick font

#

handwritten font

#

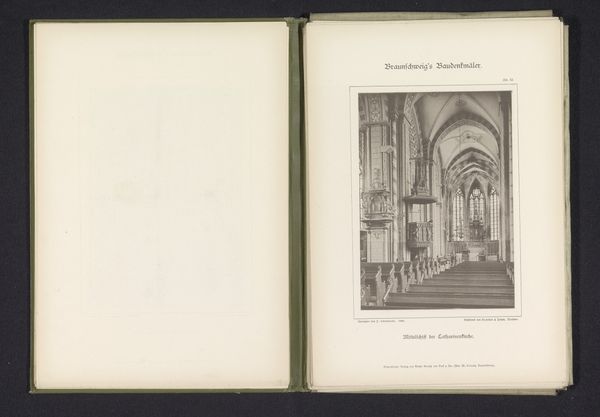

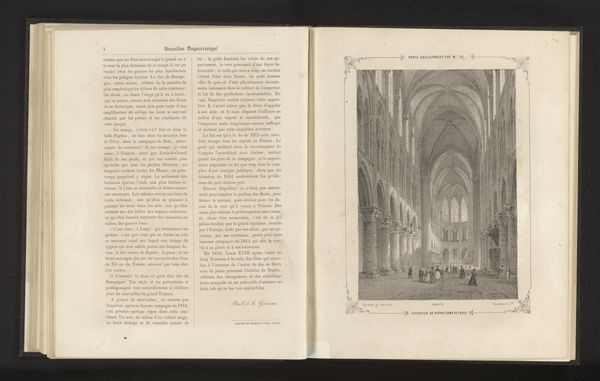

architecture

#

realism

#

historical font

Dimensions: height 164 mm, width 114 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: So, this gelatin-silver print titled "The church of St. Jacques, Antwerp" by Cundall & Fleming, dates back to before 1866. What strikes me is how meticulously the photograph captures the church’s interior; it’s almost hauntingly grand. What can you tell me about its historical relevance? Curator: Considering its public role, architectural photography like this, especially of religious spaces, played a part in constructing and disseminating cultural identity. Take note of the era—mid-19th century. Photography was still a relatively new medium, and its ability to accurately depict architecture had huge implications. How do you think it affected societal views of these grand churches? Editor: I suppose it allowed more people to see these places and possibly engage with religion in a new way, regardless of their ability to physically visit the Church itself. It makes it almost like propaganda of beauty... but that is very cynical of me, isn't it? Curator: Not necessarily cynical. Images of majestic spaces, like this church interior, had socio-political implications beyond mere documentation. Photography like this might also cement the church's power as a place of heritage worth documenting, implicitly endorsing its continuing significance in society. Consider who would commission and consume such images. Did the emerging middle class have new access to culture, and what might that have meant in that historical moment? Editor: That's a very interesting point. It does open up an entirely new way to perceive the artwork. What began as simply a stunning piece of architectural documentation opens up many considerations. Curator: Exactly! Analyzing the power dynamics inherent in how art is produced and consumed changes how we understand not just the image itself, but its role in shaping societal views. Editor: Well, I will keep that in mind from now on. It’s certainly something I’ll be pondering. Curator: Wonderful! These old images still hold lots of social information that needs re-examination.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.