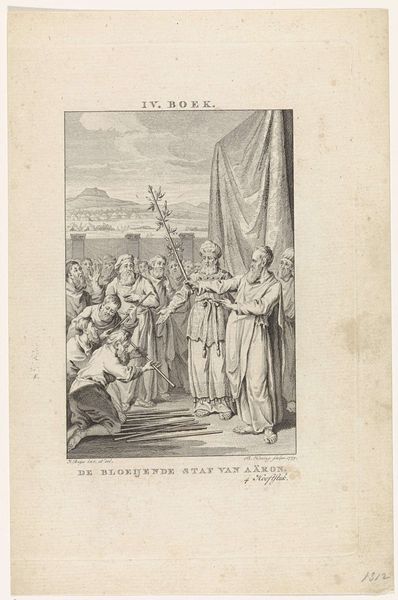

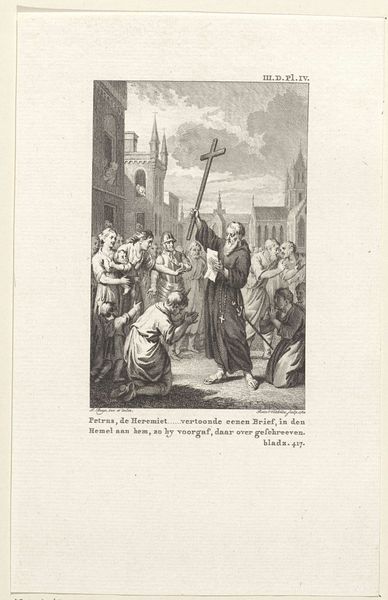

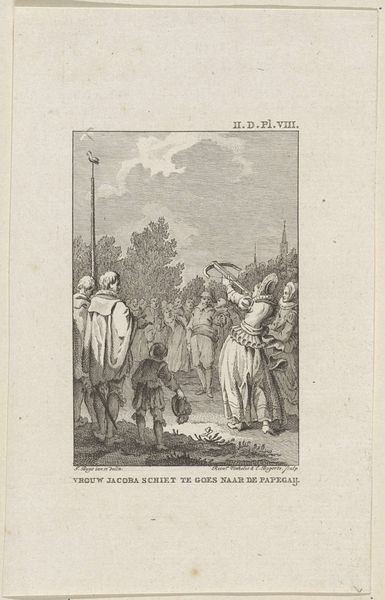

print, engraving

# print

#

genre-painting

#

history-painting

#

engraving

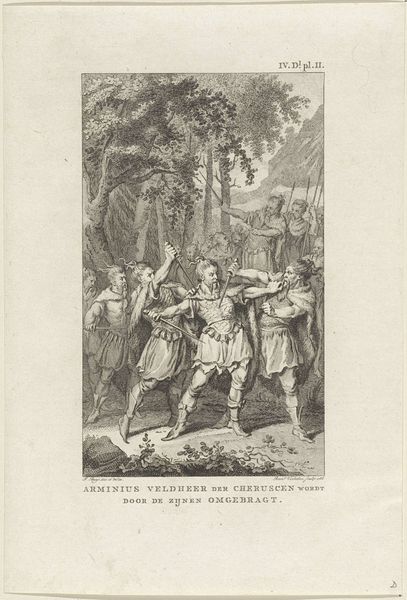

Dimensions: height 200 mm, width 137 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

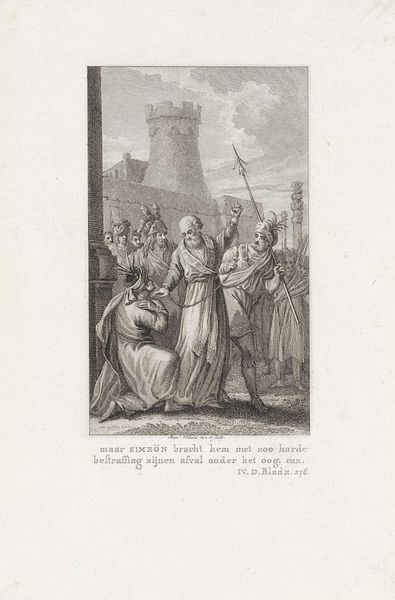

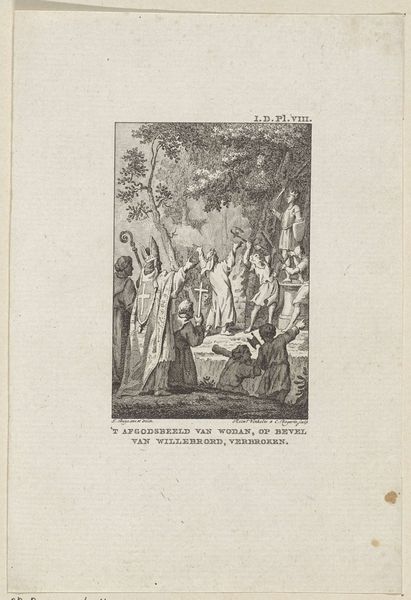

Editor: This is "Jodenvervolging in Engeland," or "The Persecution of Jews in England," an engraving by Noach van der Meer the Second, from 1784. The scene is quite stark, rendered entirely in black and white. There's a figure, seemingly an authority, gesturing toward a group of people who appear to be pleading. What symbolic significance do you see in this work? Curator: It’s a powerful depiction, isn’t it? Look closely. Notice how the authority figure, perhaps representing the English crown or church, is positioned higher, almost separate, from the huddled mass of Jewish people. His gesture isn't just pointing, it's directing, demanding. The vulnerability of the group is highlighted by their posture—heads bowed, hands clasped. It echoes centuries of forced conversions and expulsions. Can you discern any other repeating motifs? Editor: I notice crosses appearing on clothing and on top of what appears to be some sort of building. And is that a body lying on the ground? Curator: Yes, observe how Van der Meer uses Christian iconography here - not merely as a historical marker, but as a visual tool of power and oppression. Crosses emblazoned on chests of people, and church tops symbolize a system poised to either indoctrinate or expunge people based on their spiritual convictions. As for the body, it shows what is a literal symbol of sacrifice, but I wonder, is it to stay, or to flee? The title suggests more of this occurred. These visual reminders of religious dominance were tools used in solidifying cultural memory. Editor: So, it’s not just depicting a historical event, but reinforcing a certain perspective, a narrative of dominance through shared cultural symbols? Curator: Precisely. Engravings like these shaped public perception. They imprinted images of power and submission onto the collective consciousness, solidifying narratives of religious and cultural othering that unfortunately lingered for generations. Looking at it now reminds us that visual language is indeed always encoded, deliberately constructed, to affect how we view ourselves and each other. Editor: That makes me see the image completely differently, the symbolism driving a narrative with lasting consequences. Thank you for pointing all of this out!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.