drawing, pencil

#

portrait

#

pencil drawn

#

drawing

#

pencil sketch

#

pencil drawing

#

pencil

#

academic-art

#

realism

Dimensions: height 295 mm, width 219 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

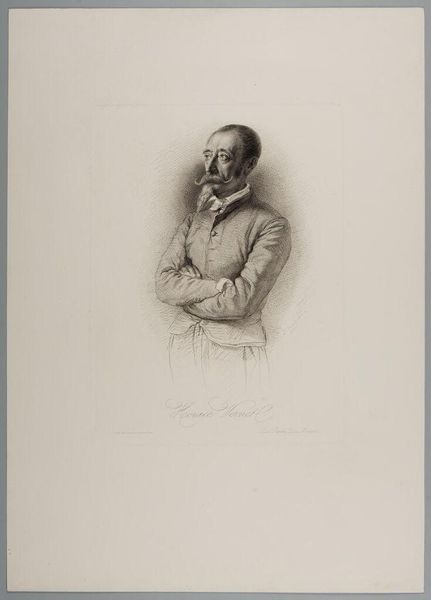

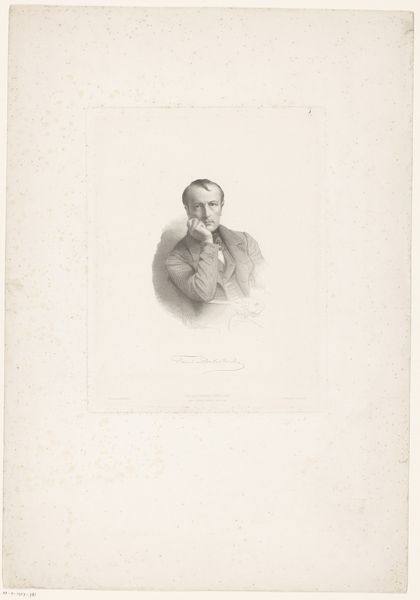

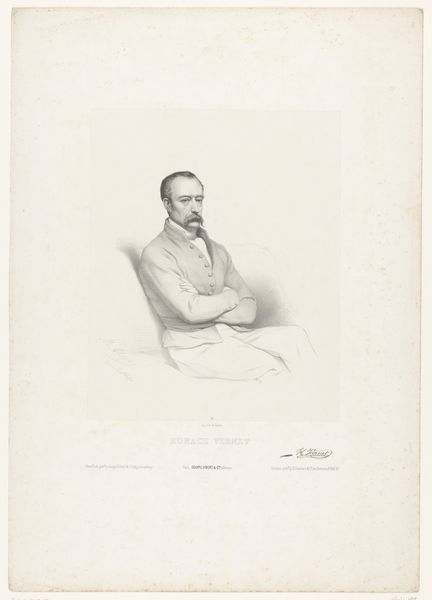

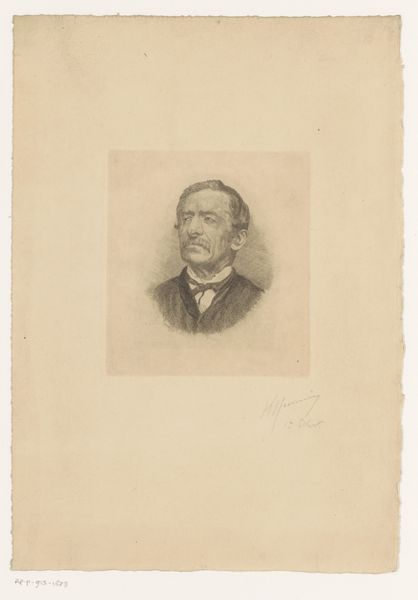

Curator: Here at the Rijksmuseum we have a striking pencil drawing by Léopold Massard created between 1832 and 1889 titled "Portret van Horace Vernet". Editor: There's a quiet intensity to this portrait, almost as if Vernet is guarding a secret. His crossed arms and somewhat stern gaze project such self-assuredness, even defiance. Curator: The artist's mastery of the pencil is quite evident. Note the delicate rendering of Vernet’s features—the meticulously drawn moustache, the way light catches the fabric of his coat. Observe how Massard used subtle gradations in tone to model form. Editor: Yes, but what's behind that form? Horace Vernet was a celebrated painter but also a controversial figure due to his associations with French colonialism and his glorification of military exploits. This drawing exists within a historical context of imperial expansion. Is it a celebration of Vernet's artistic skill, or is it indirectly valorizing his politics as well? Curator: Surely we can appreciate the technical skill without necessarily endorsing the subject's sociopolitical values. The realism with which Massard captured Vernet, particularly his eyes and knowing gaze, is undeniably masterful, a demonstration of artistic virtuosity in pencil medium. The academic style employed lends a classical feel. Editor: That’s a fair point, and yet the sheer existence of portraiture as a genre has to be examined through its inherent biases. Who gets memorialized, and why? Vernet certainly held a privileged position within society, enabling this drawing's existence, yet so did Massard. Their shared circles raise important considerations concerning power, legacy and access. Curator: Indeed, though if we focus again on the image itself, we cannot dismiss the artist's capability in creating such visual detail. This adds significant value in art history discourse concerning not just representation but technique itself—namely draftsmanship. Editor: A valid point. But my reading underscores how inseparable aesthetic judgements are from historical and societal constructs. Massard's portrait prompts us not only appreciate technique but analyze who wielded the pencil, towards what ultimate ends? Curator: Perhaps a combination is apt, enabling more rich discussion surrounding technical craft against nuanced social reading; together enhancing meaning rather dividing along separate schools. Editor: Agreed. This portrait is a starting point of artistic and contextual inquiry, reminding of complex dialogues and legacies woven between portrait, politics, and practice.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.