#

natural stone pattern

#

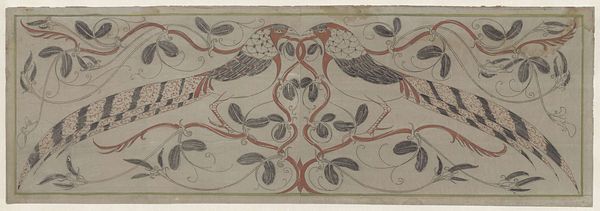

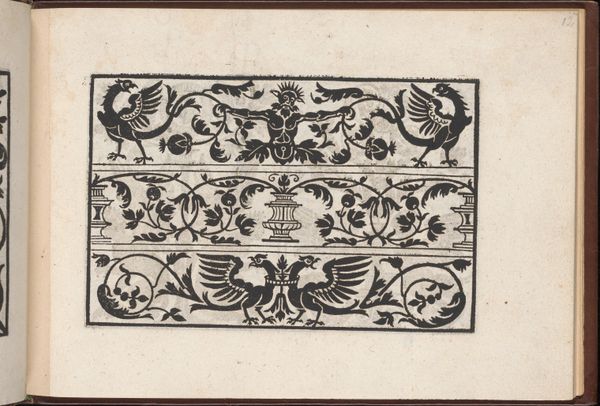

aged paper

#

toned paper

#

water colours

#

pastel soft colours

#

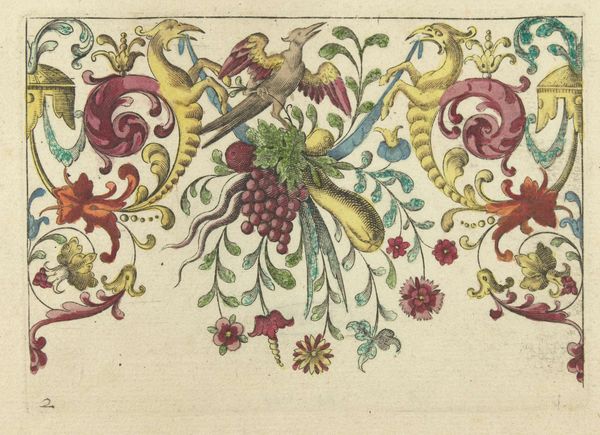

ink paper printed

#

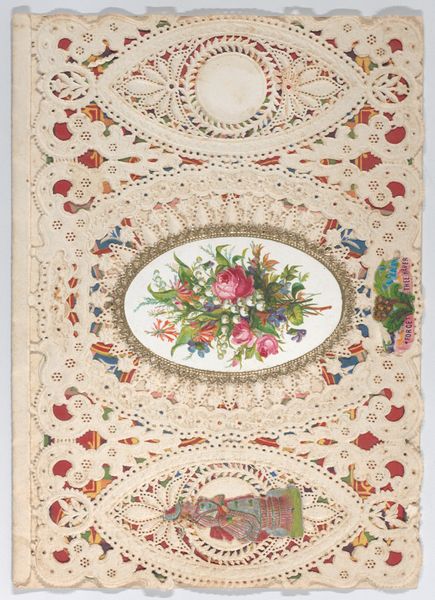

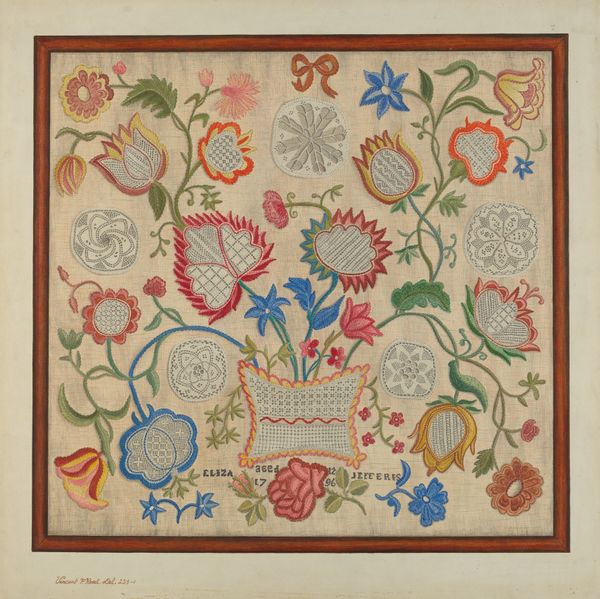

flower

#

watercolour bleed

#

watercolour illustration

#

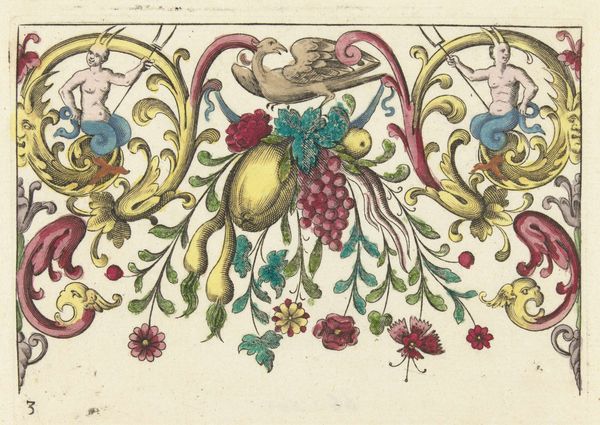

layered pattern

#

watercolor

Dimensions: height 95 mm, width 258 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: "Bloemenranden," or "Floral Borders," dating from around 1770 to 1808, is a watercolor on paper by Jan Brandes. I find the simple beauty quite charming; what's your initial impression? Editor: I am drawn to the use of such delicate watercolors on paper. It feels almost like a gentle whisper. The muted pastel colors and simple composition suggest an innocent celebration of the natural world, but can these works tell us something deeper? How do you interpret this work, particularly considering its time? Curator: Well, let's think about Brandes's world. This was a period saturated with colonial expansion. Given the location, the Dutch East India Company would have been extremely active. What if these delicate floral arrangements aren't just pretty decorations? Perhaps they represent a curated, controlled vision of nature, mirroring the way European powers sought to manage and exploit the resources and populations of the countries they colonised? The flowers themselves, where did they originate? Are these local flowers, or ones brought in from abroad? Editor: That's fascinating, the idea of imposed order reflecting colonial ambitions. So, this watercolor, rather than being merely decorative, might actually reveal the complex relationship between Europe and the rest of the world? I am really beginning to consider the art as propaganda. Curator: Precisely. The very act of depicting and cataloging nature becomes a form of control, an assertion of dominance. Consider how botanical illustrations were often commissioned by wealthy landowners and scientists, keen to display and categorize their findings, furthering the practice. Who were these flower borders made for and why? These are the vital questions. Editor: I hadn't considered that before, but framing it in the context of colonialism gives it a completely new meaning. Thanks so much. Curator: It's crucial to consider the social and political implications of even the seemingly most innocent of artworks!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.