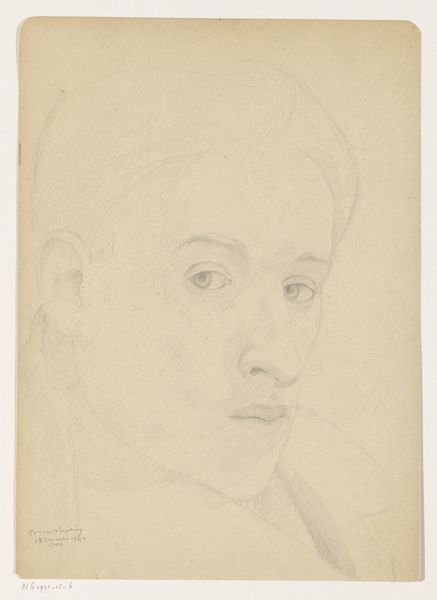

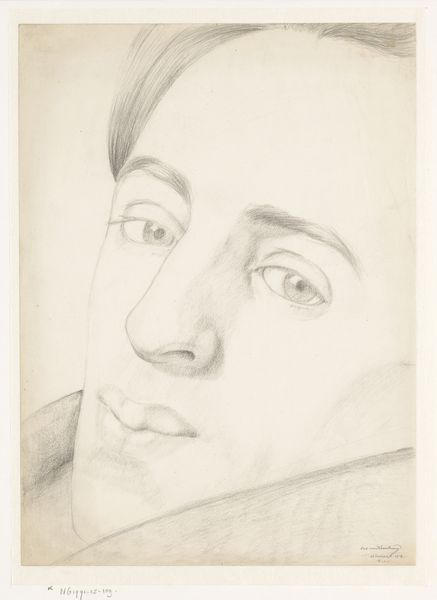

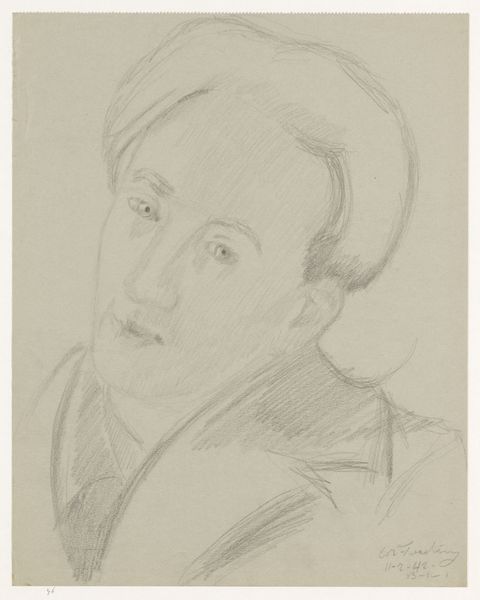

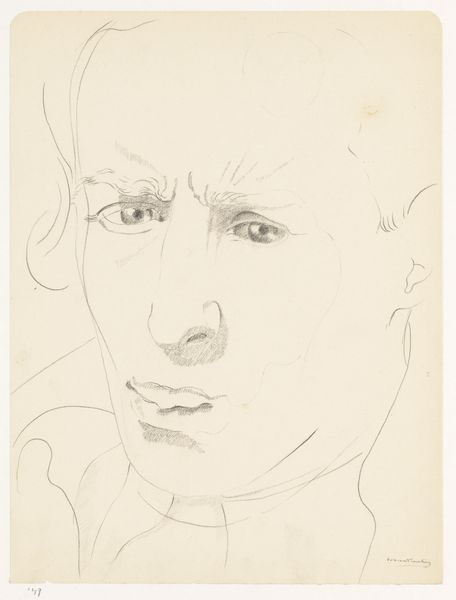

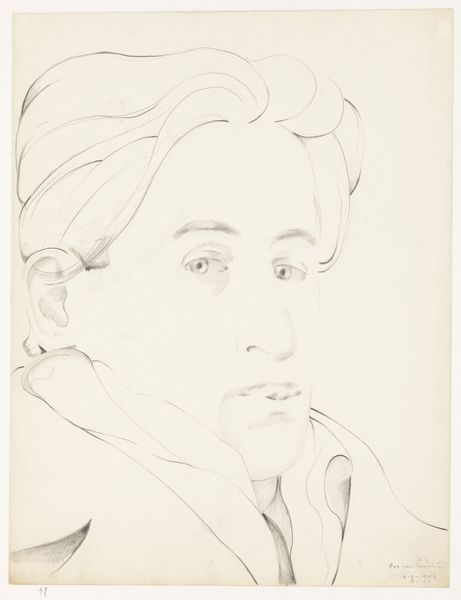

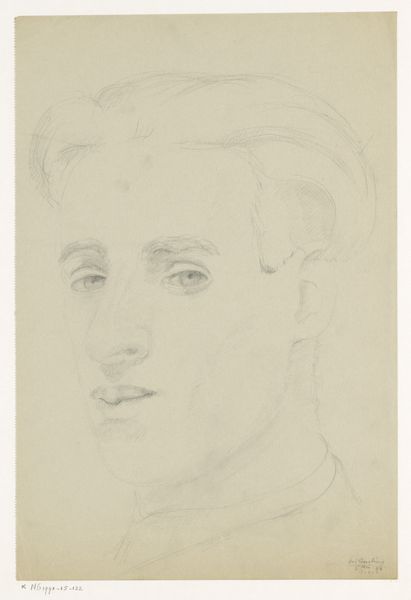

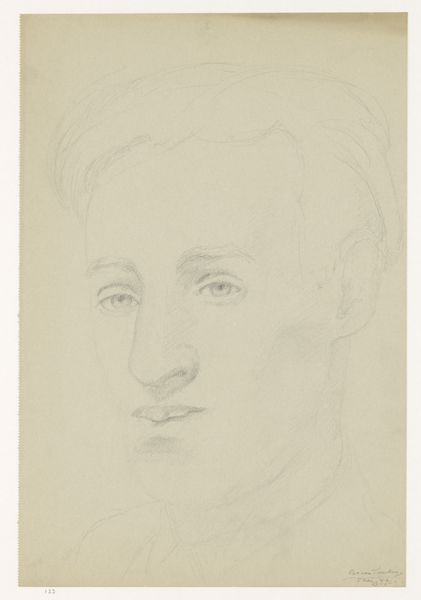

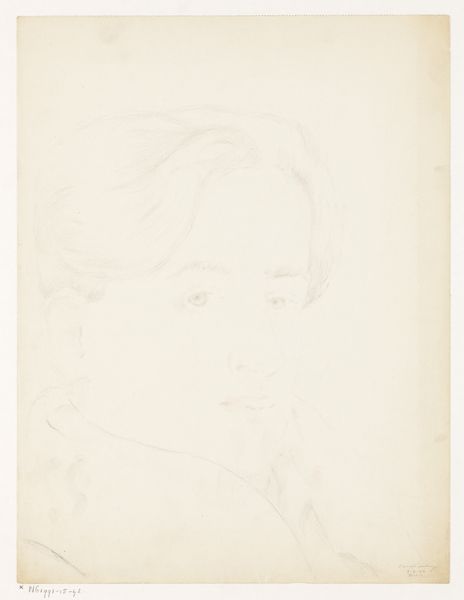

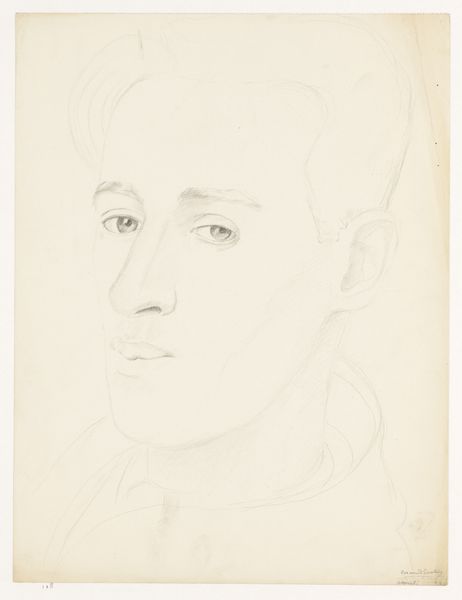

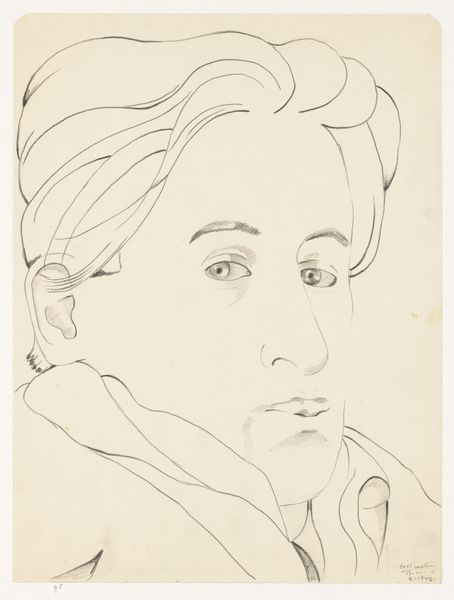

Zelfportret, voorovergebogen met hand op schrift Possibly 1941 - 1948

0:00

0:00

corvanteeseling

Rijksmuseum

drawing, pencil

#

portrait

#

pencil drawn

#

drawing

#

self-portrait

#

pencil drawing

#

pencil

#

portrait drawing

#

realism

Dimensions: height 36.0 cm, width 24.0 cm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Welcome. Before us, we have a pencil drawing from the Rijksmuseum’s collection: Cor van Teeseling's "Self-Portrait, leaning forward with hand on scripture," likely created sometime between 1941 and 1948. Editor: The delicacy of the line work strikes me immediately. It's almost as if he’s drawn his own ghost – vulnerable, pensive...melancholy even. Curator: It is certainly a revealing portrait, wouldn't you agree? The positioning of the hand atop the scripture introduces a fascinating intersection of the artist, faith, and perhaps the written word as a means of self-expression or contemplation. The timing of its creation, during and shortly after World War II, cannot be overlooked either. How might personal identity intersect with broader socio-political narratives during times of conflict? Editor: The hand – an open hand resting on scripture - is a recurring motif within religious art, a sign of offering or perhaps absolution. Consider the implications here; the artist presents himself not only as subject but also as supplicant. And yet, the "scripture" feels...unfinished, less defined. Is this faith providing solidity or still searching for resolution? The tentative quality of the line also invites psychological interpretations. Curator: Indeed. Perhaps this lack of completion can also act as a metaphor for societal reconstruction. There is the artist, bearing witness to trauma; trying to write a different narrative and coming to terms with a postwar world where systems of belief were tested and fractured. Consider this work in conversation with similar examples of self-representation by artists experiencing displacement, marginalization, or social upheaval. How does Van Teeseling leverage his identity? What strategies did they use to articulate collective sentiments about self and community? Editor: To consider, too, the simple, readily accessible medium: the humbleness of pencil on paper. Here, perhaps, the medium enhances accessibility: there is no artifice, but simply the barest translation of self to representation; accessible equally to both artist and observer. It renders him, this highly private and personal piece, more available to those facing trauma or dislocation themselves. Curator: What are your closing thoughts, considering how images persist through time? Editor: In revisiting his quiet self-portrait today, the persistent symbolic power of scripture, faith and self reflection seems timeless in our human need to wrestle with inner meaning and external circumstance. Curator: I agree. It's a poignant reminder of the importance of situating individual stories within wider, unfolding histories, so that collective catharsis and remembrance can also endure.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.