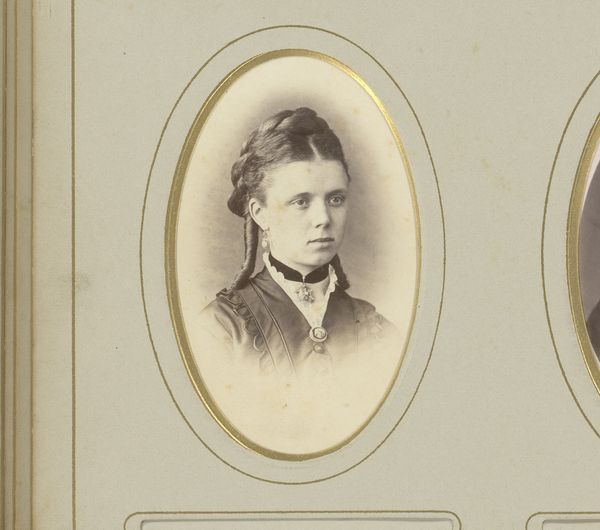

photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

portrait

#

photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

Dimensions: height 85 mm, width 51 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

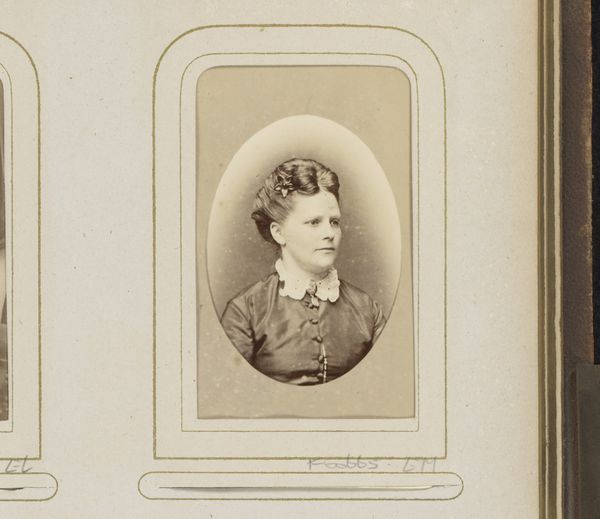

Curator: Let’s explore this captivating “Portret van een vrouw,” dating back to 1874 and crafted through a gelatin-silver print technique by Ch. Verbeke-Schodts. Editor: The oval format immediately creates an intimate space, doesn’t it? The sepia tones give it a muted, almost melancholic feeling, like a window into a bygone era. Curator: Absolutely. The choice of gelatin-silver print here is significant. By the 1870s, this process offered greater tonal range and sharper detail compared to earlier photographic methods. It facilitated mass production but also a certain consistency, which speaks to the burgeoning market for portraiture within the rising middle class. Editor: It’s interesting how that democratization intersects with social expectations for women at the time. This woman's attire – the high-necked dress and the simple jewelry – suggests a certain modesty and adherence to societal norms, doesn’t it? A representation shaped by, and shaping, the identity of women in 19th century. Curator: Precisely. The photograph itself becomes a commodity, reinforcing class and gender distinctions. Note, too, the elaborate backing board, complete with the photographer's branding. This highlights the industrial aspect – the studio as a factory, churning out images that uphold the status quo through materials and manufacturing. Editor: But it’s not devoid of individuality. Look closely, the slightly averted gaze, the delicate curl escaping her updo... there's a quiet strength. Perhaps a subtle challenge to the passive role prescribed to women. Also, I am quite interested in who might commission a piece like this back then. Curator: These details hint at the push and pull between individual expression and social constraints. Understanding the technology allows us to see both how her image was constructed and also potentially how she chose to participate in that construction through posing, costuming, and so on. What about her relationship to labor? Was she able to commission it because she or a male relative was participating in industrial or trade endeavors? Editor: Food for thought indeed. It is almost as if through this photographic glass, darkly, we can piece together a small section of a greater reflection on womanhood and industrial practices of the time. Curator: Ultimately, it calls to mind an observation not just about the artwork, but what society tells itself it values.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.