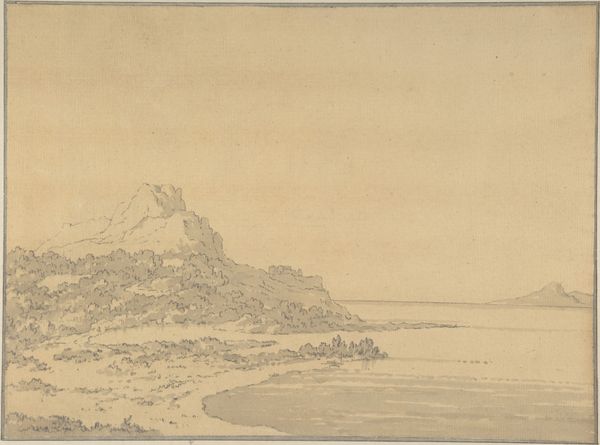

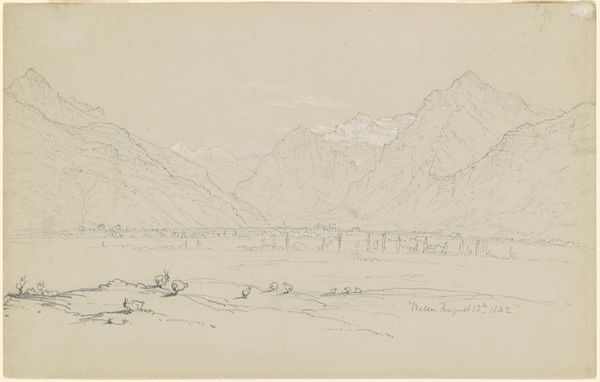

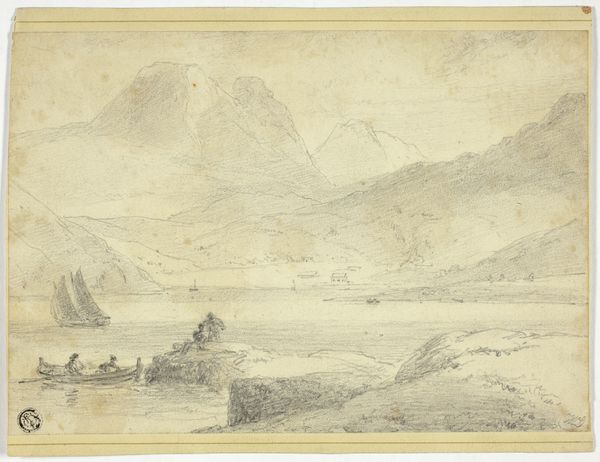

Dimensions: sheet: 18 × 27.2 cm (7 1/16 × 10 11/16 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

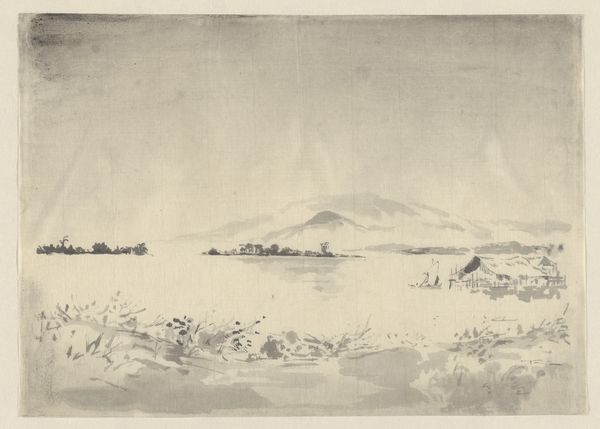

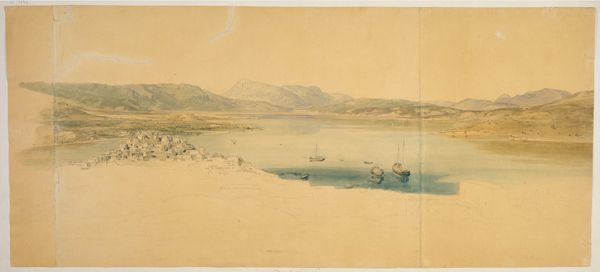

Curator: Frederic Edwin Church rendered this pencil drawing, "Magdalena River, New Granada, Equador," in 1853, showcasing the artist’s eye for detail within the grand scale of the South American landscape. Editor: Immediately, I notice how tranquil this scene appears. The muted tones create an almost dreamlike quality, yet there's a crispness in the details that prevents it from feeling entirely ethereal. Curator: The image presents an interesting intersection of colonialism, nature, and faith. Notice the juxtaposition of the small boat on the river against the imposing, snow-capped mountains in the background. It brings to the fore issues around exploration, expansion, and the claiming of land. The inclusion of a small church is also evocative. Editor: That's insightful. I was struck by that church, too. The thatched roof and simple cross give it a potent symbolic charge: a mark of established faith transplanted onto a foreign and presumably Indigenous landscape. I wonder if the artist intended to highlight the subtle tensions within that cultural exchange. The very composition seems weighted, with that small settlement taking the visual foreground to that huge mountain's backdrop. Curator: It's definitely a dialogue worth investigating, placing the dominance of landscape with that of cultural and societal shifts. Church was associated with the Hudson River School movement and had ties with luminaries like painter Thomas Cole, and scientist Alexander von Humboldt, so ideas around Romanticism and Manifest Destiny are all there, intertwined. The inclusion of local vegetation offers a contrasting perspective. Editor: The vegetation surrounding the thatched dwelling feels deliberately placed as well: an almost Eden-like association of abundance and perhaps purity that counters those mountain’s potential sublimity. I find myself wondering about the perspective: the eye is drawn from left to right, moving between nature's grand scale and humankind’s settlement within it. What feelings and social questions did this kind of iconography stir within his original viewers? Curator: Precisely! It's this interplay between nature, progress, and civilization, presented during a time of great social and geographical transformation that makes this piece particularly relevant even today. Editor: Looking at it now, after this conversation, I'm struck again by how charged such seemingly calm depictions of landscape can truly be. Curator: I concur completely. By examining the historical context and considering those power dynamics, the artwork allows us to contemplate our own positionality within those narratives still unfolding today.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.