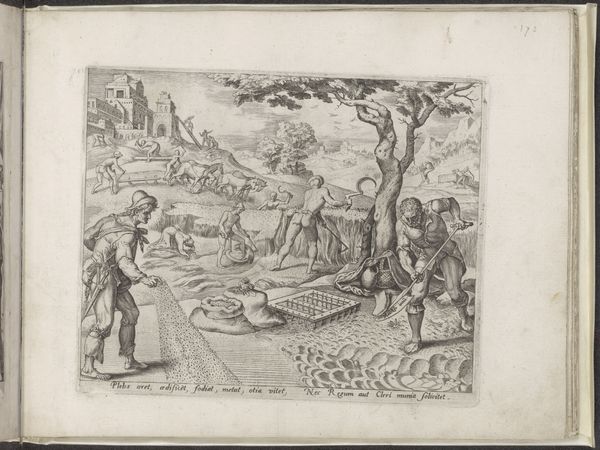

print, engraving

# print

#

pen sketch

#

old engraving style

#

landscape

#

figuration

#

genre-painting

#

history-painting

#

northern-renaissance

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 204 mm, width 246 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

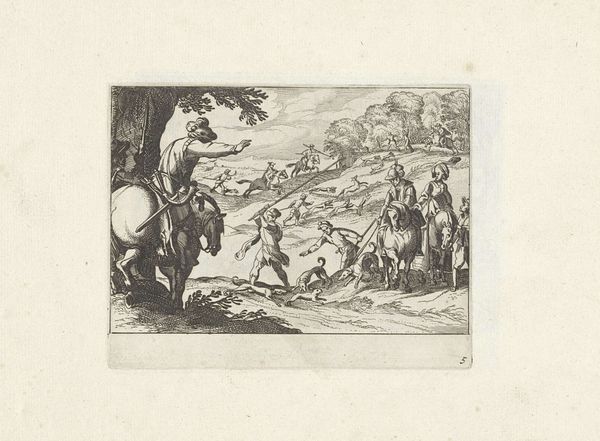

Curator: Standing before us is an engraving titled "Arbeid is de taak van de derde stand," or "Labor is the task of the third estate," which historians believe was produced sometime between 1565 and 1635. Editor: It immediately strikes me as a stark portrayal of relentless work. The landscape is teeming with figures engaged in different forms of labor, their postures reflecting hardship and perseverance. There’s something quite somber about it despite the active scene. Curator: Exactly. It's vital to remember the social context. Prints like these served to reinforce societal hierarchies. The "third estate," the commoners, were explicitly depicted as those whose burden it was to perform labor. Editor: The figures almost seem allegorical, as if they represent broader societal forces at play. Consider how the image depicts an entire community engaged in essential agricultural tasks. Could the oxen and the sowing of seeds be a call to prosperity achieved solely through their work? Curator: Undoubtedly. The image perpetuates a certain ideology. We see the working class tied to the land, their lives dictated by physical toil. There is that building at the top; they're making the structures which are more for someone else than them. The text at the bottom literally enforces the point - commoners are not for high affairs, or religious works! Editor: It makes me wonder about the serpent. It seems almost strategically positioned overlooking everything; is that a possible link to the "original sin", where manual labor and human effort were divine retribution? That connects so well with the rest of the composition! Curator: Intriguing thought. And it reinforces how the ruling classes co-opted religion in a period of conflict to legitimize power, ensuring social order through imagery. But here, at the Rijksmuseum, centuries later, we can question the politics. Editor: Seeing it now, through our contemporary lenses, reveals both the historical weight and the continued power dynamics encoded in visual representations of labor. It's a fascinating artifact. Curator: I concur; art provides historical perspectives into societal biases. This print urges us to be wary of such enduring rhetoric, whether it is found in politics, society, or art.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.