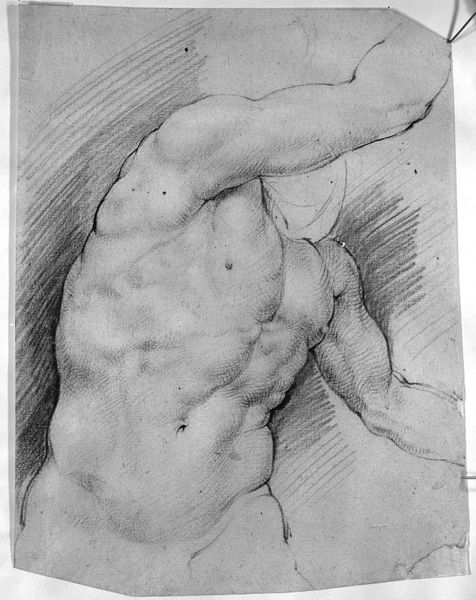

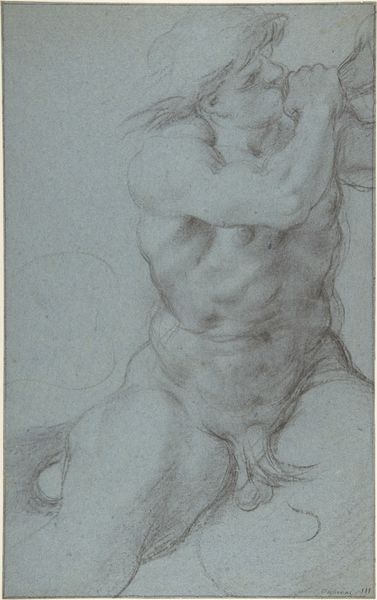

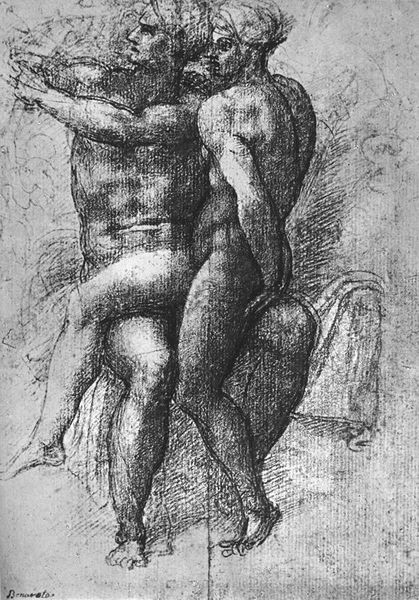

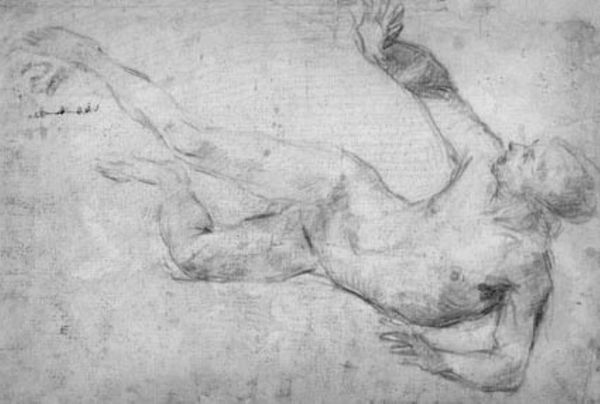

Torso. Belvedere. Front view of the antique sculpture. 1628 - 1629

0:00

0:00

drawing, paper, ink

#

drawing

#

figuration

#

paper

#

11_renaissance

#

ink

#

academic-art

#

nude

Dimensions: 273 mm (height) x 172 mm (width) (bladmaal)

Curator: Today, we're looking at a drawing by Willem Panneels from 1628-1629 titled "Torso. Belvedere. Front view of the antique sculpture," currently held at the SMK, the Statens Museum for Kunst. Editor: It hits you immediately, doesn't it? That raw, almost brutal rendering of the human form. So much ink to achieve the intense shading; it’s heavy, monumental. Curator: Absolutely. It's a drawing rendered in ink on paper, depicting a male nude, specifically the Belvedere Torso. You can sense Panneel's engagement with academic art. He’s wrestling with classical ideals of the body. Editor: Wrestling is right! Look at the pressure of those lines. It seems he is physically etching out form through the medium. Paper isn't just paper here; it’s become muscle, bone. Curator: And, of course, the drawing itself is secondary. It is a copy of a Roman marble sculpture, which would have already been a copy of a Greek bronze. Editor: Ah, the infinite regress of artistic reproduction. It highlights the social labor of the artisan: all the work hours gone into quarrying marble and creating each generation of art, how do those laborers find a connection with idealized concepts? Curator: Well, Panneels may have also viewed the work and labor as part of his process. His close study and academic interpretation of the male form in art are highlighted here through copying the initial torso form. Editor: It’s interesting how he hones in on this fragment. A torso, deliberately incomplete. Does the fragment enhance its power, its potential for idealized completion? Or is Panneels just focused on honing his ability to render light and shadow? Curator: It reminds us that so much of artistic tradition is built upon appropriation, on reworking and reinterpreting what has come before. Perhaps, the broken figure can speak for every break we've put onto matter for our vision of the world, be they cultural and physical. Editor: In that light, the image transforms into an interesting depiction of labor's complicated relationship with its subjects. In our time today we rarely engage with a full picture but snippets instead. Curator: I never thought that looking at such an old figure of this ancient image can reflect to so much complexity about now. Editor: Yeah! A conversation through time made from matter through a matter of time.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.