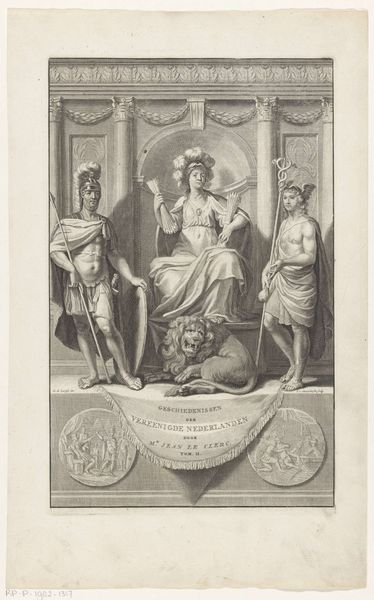

drawing, graphite, engraving

#

drawing

#

neoclacissism

#

pencil sketch

#

charcoal drawing

#

charcoal art

#

pencil drawing

#

graphite

#

portrait drawing

#

academic-art

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 322 mm, width 200 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have Ignaz Unterberger's "Portret van Franz Georg, Ritter von Kees," an engraving dating to the late 18th century. Editor: It has an imposing feel. The sharp lines lend an almost neoclassical formality, yet there's a softness around the face that hints at something more... vulnerable? Curator: The artist masterfully uses line weight to create depth and contrast. Note how the meticulous details in his robe are offset by the smoother rendering of the face. The composition seems to draw on the academic style of that period. The gaze is what truly anchors the composition. Editor: Absolutely. And given the subject’s position within the court of Joseph II, I see this portrait as speaking to ideas of power and status. The book, the ornate clothing—these are symbols of privilege in a society undergoing immense change. One almost feels that he must clutch on to it all with two hands lest everything falls. Curator: You can observe Unterberger subtly incorporating classical motifs such as the bust crowned with laurels behind von Kees that speaks to Enlightenment ideals while grounding his subject in the present. And look how the textures and varying degrees of shading are achieved in print form, with delicate hatching techniques to evoke form. Editor: But what did "enlightenment" really mean for the majority of people? For the peasantry who toiled while elites like von Kees enjoyed positions of power? The bust's presence alongside Kees doesn’t just denote ideals—it asks whose ideals are centered and who is excluded? This work is far from a neutral aesthetic exercise; it entrenches very clear power dynamics and values. Curator: That's certainly one reading. Yet, the very precision of the engraving elevates its status as an artwork with formal merits. The artist’s technique showcases incredible control, balancing darkness and light. The engraved medium and framed presentation indicate that von Kees’ likeness would be widely distributed as propaganda. Editor: Fair point. By viewing these kinds of works we can interrogate visual strategies the powerful use to legitimise their place within the hierarchy. We may better arm ourselves with such analyses when we examine today's visual media. Curator: Yes. When looked at from both of our perspectives, we notice details we may have missed on our own. Editor: Absolutely. Understanding power relations is central to unveiling a work like this one.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.