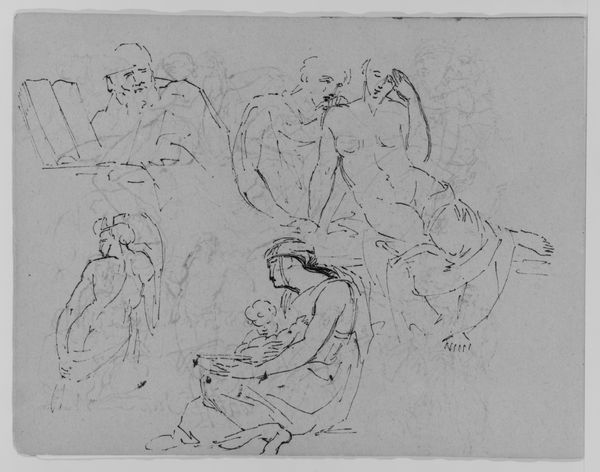

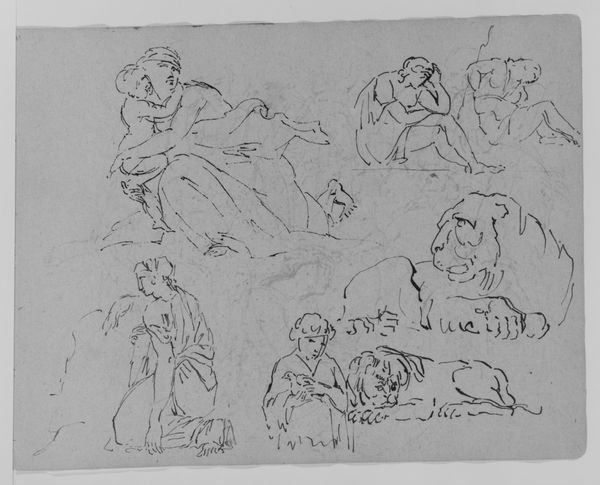

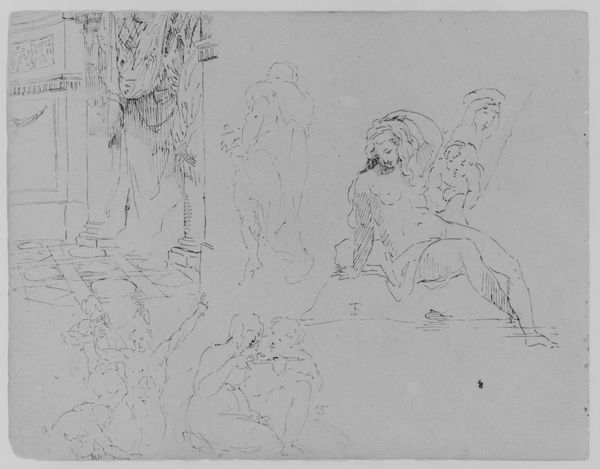

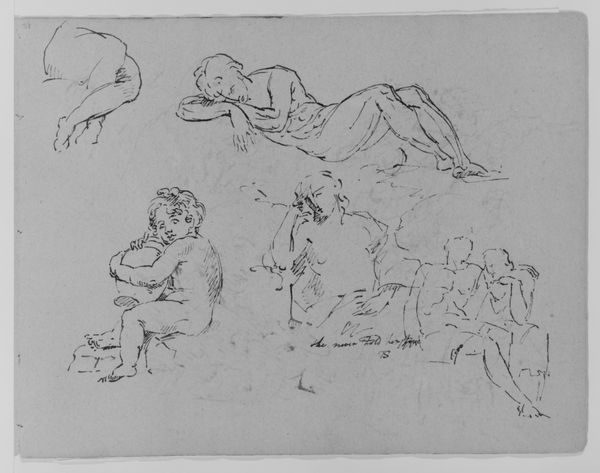

![Child with Dog; Two Figures in Encounter; Two Figures and Child Attending to Dying Male [?]; Figure on Deathbed (from Sketchbook) by Thomas Sully](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fd2w8kbdekdi1gv.cloudfront.net%2FeyJidWNrZXQiOiAiYXJ0ZXJhLWltYWdlcy1idWNrZXQiLCAia2V5IjogImFydHdvcmtzL2IxOGZiZDNiLTAyN2ItNDc0Yi04MTBjLWJkZDIxMDA3ODkxMy9iMThmYmQzYi0wMjdiLTQ3NGItODEwYy1iZGQyMTAwNzg5MTNfZnVsbC5qcGciLCAiZWRpdHMiOiB7InJlc2l6ZSI6IHsid2lkdGgiOiAxOTIwLCAiaGVpZ2h0IjogMTkyMCwgImZpdCI6ICJpbnNpZGUifX19&w=3840&q=75)

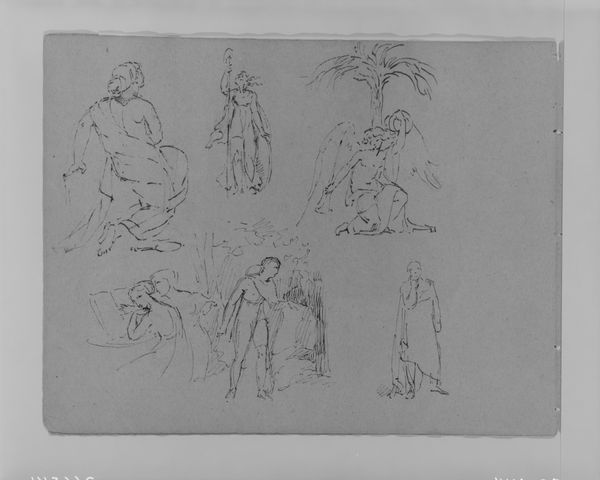

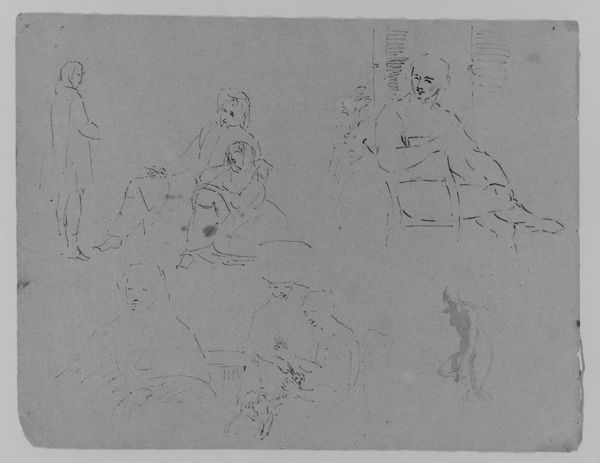

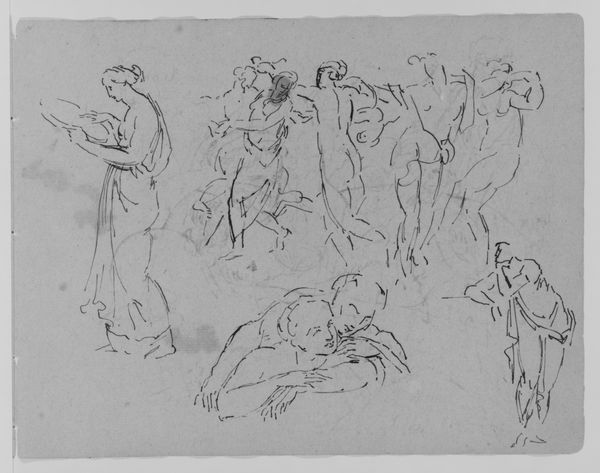

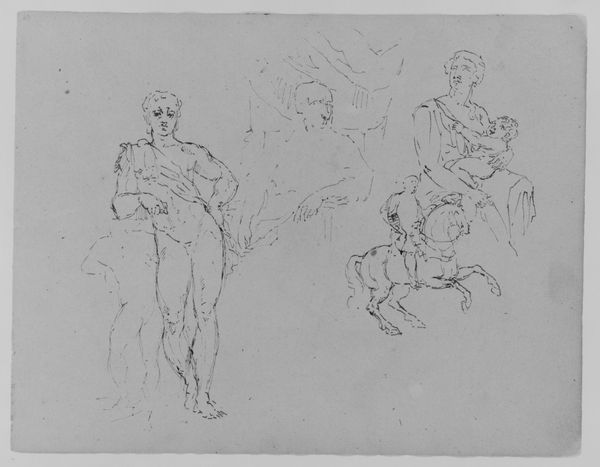

Child with Dog; Two Figures in Encounter; Two Figures and Child Attending to Dying Male [?]; Figure on Deathbed (from Sketchbook) 1810 - 1820

0:00

0:00

drawing, paper, ink, pencil, pen

#

drawing

#

narrative-art

#

death

#

dog

#

classical-realism

#

figuration

#

paper

#

ink

#

child

#

group-portraits

#

romanticism

#

pen-ink sketch

#

pencil

#

pen

#

history-painting

#

academic-art

Dimensions: 9 x 11 1/2 in. (22.9 x 29.2 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Here we have a sketch, dating from about 1810 to 1820, by Thomas Sully. It's currently held at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The work, whose full title is "Child with Dog; Two Figures in Encounter; Two Figures and Child Attending to Dying Male [?]; Figure on Deathbed (from Sketchbook)," employs pen, ink, and pencil on paper. Editor: There’s a rawness to this piece. The scratchy lines, the immediacy of the gestures...it feels deeply personal and somewhat melancholic, despite the active scenes portrayed. It's a world caught between light and shadow. Curator: The combination of domesticity and mortality is a striking feature. Consider how the rendering of "Child with Dog" evokes notions of innocence and familial bonds. Placed alongside the scene of what appears to be a deathbed, it provides a profound contrast, a juxtaposition of life's beginnings and endings. These thematic dualities resonate with Romanticism, as does its overall tone. Editor: I agree. The sketch-like quality emphasizes the hand of the artist, the act of making. We see the material vulnerability: ink bleeds into paper; pencil smudges to create shading. This connects directly to the artwork’s subject, that being life’s own material vulnerabilities – illness, care, death. Look how the pen strokes cluster around the dying man's face, illustrating attention, concern. We see care literally drawn into the piece. Curator: Yes, it evokes complex gendered and emotional labor dynamics. Who is attending to this figure, and what social roles dictate that care? The ambiguous figures surrounding the dying man also beg questions concerning who has access to medical assistance and palliative care at this historical juncture, and within this family context. Editor: The lack of finish actually strengthens the work's communicative force, making it appear urgent, immediate. These aren’t gods or heroes, but ordinary people dealing with material existence and its realities: birth, love, sickness, death. Curator: Absolutely. By framing the quotidian, Sully gestures toward those unseen and unacknowledged spaces where lives are negotiated and redefined. His figures, caught in this intimate moment of both support and bereavement, highlight the intersectional issues facing families and communities even two centuries ago. Editor: Reflecting on Sully’s materials allows a different vantage into those long-ago material realities; sketching isn’t expensive sculpture, or imported canvas and paint; this drawing brings us almost as close as possible to one 19th century artist's world as he encountered it and then made something with it. Curator: Thank you. Looking closely at Sully's sketches through this interpretive frame really does expose the often-obscured yet significant nuances shaping 19th century familial relationships and the performance of social roles during moments of crisis and tenderness.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.