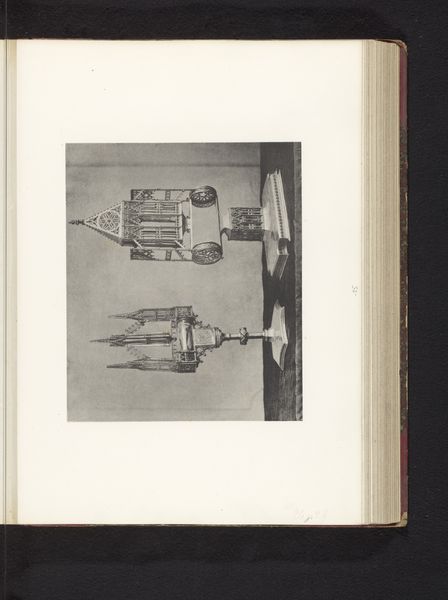

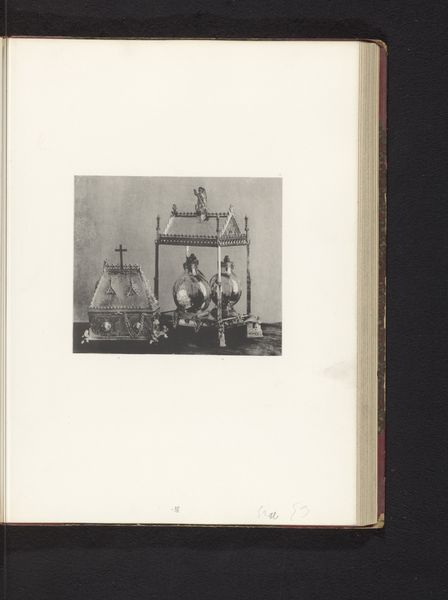

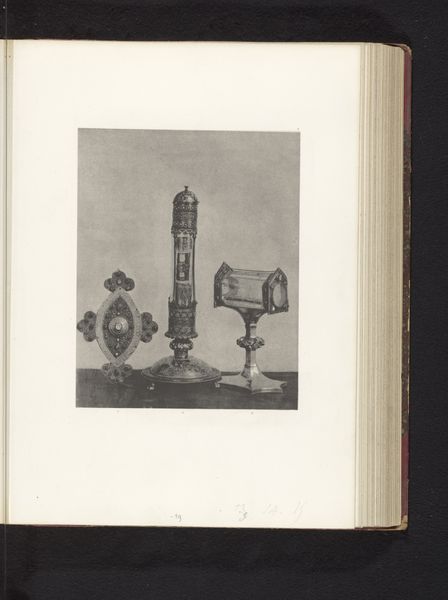

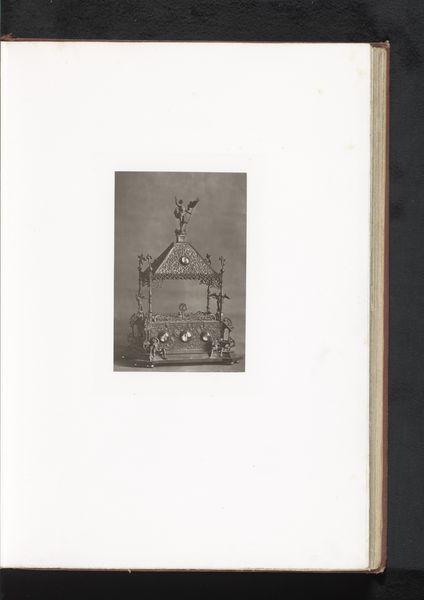

Monstrans uit de Sint-Waltrudiskerk in Mons, opgesteld op een tentoonstelling over religieuze objecten uit de middeleeuwen en renaissance in 1864 in Mechelen before 1866

0:00

0:00

photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

medieval

#

photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

Dimensions: height 250 mm, width 198 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: This is a photograph by Joseph Maes, taken before 1866, depicting a monstrance from the Saint Waltrude Church in Mons. It was exhibited at an exhibition in Mechelen. It's stark, the gelatin-silver print lending a certain austerity. How do we unpack the power dynamics inherent in depicting religious artifacts through a photographic lens? Curator: That’s a crucial question. The act of photographing itself is an assertion of power. In the mid-19th century, think about the rise of photography coinciding with increasing secularism and the challenge to traditional religious authority. This photograph, taken for an exhibition, isn’t just a neutral record; it’s a framing of faith, putting it on display for a public audience that is increasingly questioning its role. How does the photograph position the monstrance, not just as a religious object, but as a cultural artifact, maybe even a relic of a declining power structure? Editor: So, the context of the exhibition is crucial too? Curator: Absolutely. Consider the setting: an exhibition. These spaces are defined by specific audiences, often from privileged socio-economic backgrounds. By framing religious objects for an exhibition, its initial meaning and significance are altered for an elitist audience who were likely decontexualized from that spiritual purpose. Further, it renders these objects as mere artifacts, removed from their initial, sacred use. What about the very notion of capturing what is supposed to be sacred and unrepresentable through this photograph? Is it a demonstration of control? Editor: It is fascinating how photography could both document and dissect religious authority in that era. Thanks for this enlightening insight. Curator: The act of looking becomes a site of analysis, especially when the gaze involves power dynamics and shifts in cultural narratives. Food for thought!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.