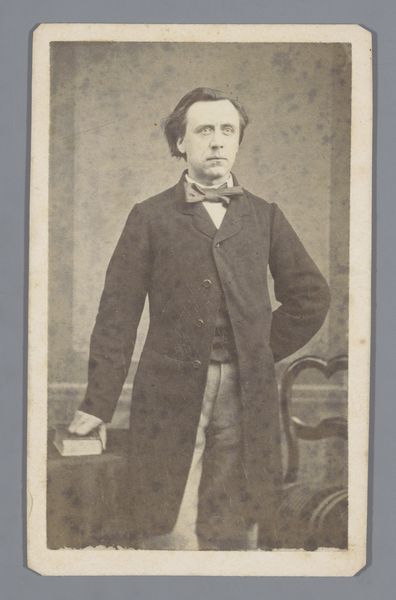

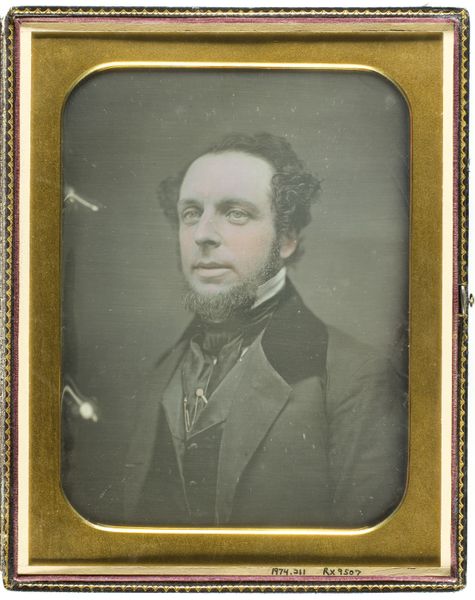

daguerreotype, photography

#

portrait

#

daguerreotype

#

photography

#

realism

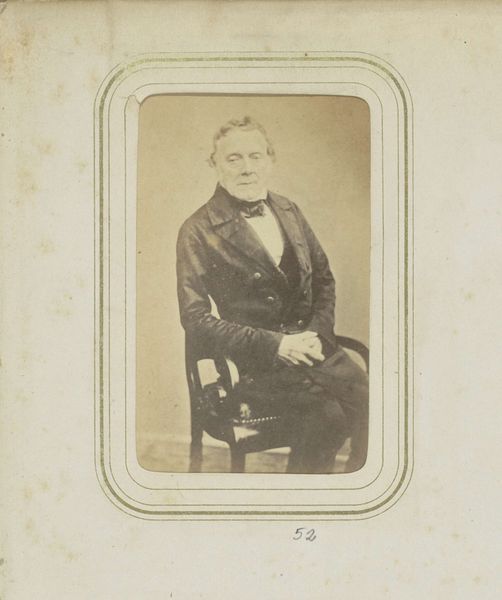

Dimensions: height 169 mm, width 121 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: What immediately strikes you about this photograph? The National Collection holds this remarkable portrait—a daguerreotype, titled *Portret van Johannes Jacobus Prins*. Dating roughly from 1855 to 1870, it is simply arresting, isn't it? Editor: It’s the palpable weight of expectation, of societal demand etched onto his face, wouldn't you agree? There is something in his eyes that screams "burden." Curator: The daguerreotype as a medium certainly lends itself to that reading. The sitter would need to maintain complete stillness during the lengthy exposure time; what might seem solemn to our contemporary eyes may, in fact, register the physical difficulty inherent in the photographic process itself. Editor: But surely it speaks volumes about nineteenth-century notions of masculinity. A stoic pose as performance? What are the socio-political pressures informing Prins’ representation, wouldn’t you agree that understanding the power dynamics is key to unpacking this portrait? How much of this is performative, in a heteronormative context, do you think? Curator: Context, as always, is everything. During this period, photography was still novel; the desire to present a respectable image would certainly be amplified, particularly within a bourgeois setting. While one might read performativity, it may also reflect social mores dictated by the rising middle class in 19th century Europe. We must consider the audience that images like this were aimed at. Editor: Precisely! And isn't this act of looking back at the male gaze also a contemporary one? This is a negotiation of representation, wouldn’t you agree, for Prins, as much as for ourselves, perhaps unconsciously revealing some aspect of male insecurity of his time? We need to ask, what expectations do we put onto gender to allow these readings? Curator: Fascinating. The daguerreotype freezes a moment, a very material link to the past. Studying the object gives us a means of asking deeper questions and looking at societal change and power structures from an intersectional point of view. Editor: Exactly. Art provides a lens—and sometimes a mirror—for understanding, challenging, and transforming the world around us. Thank you.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.