photography

#

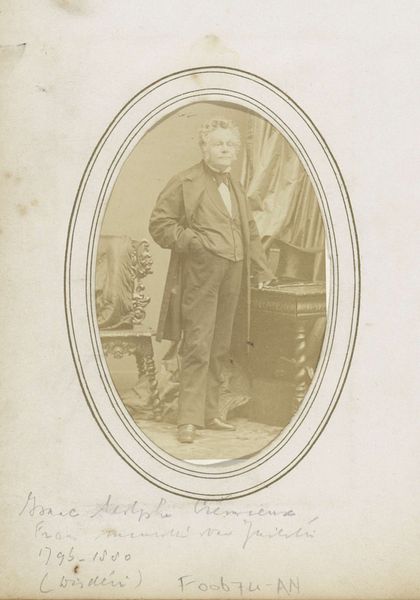

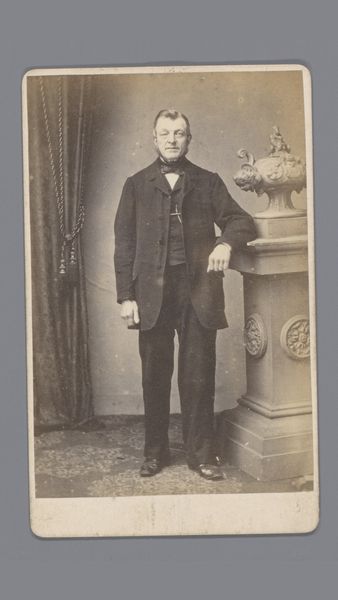

portrait

#

photography

Dimensions: height 92 mm, width 55 mm, height 104 mm, width 59 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

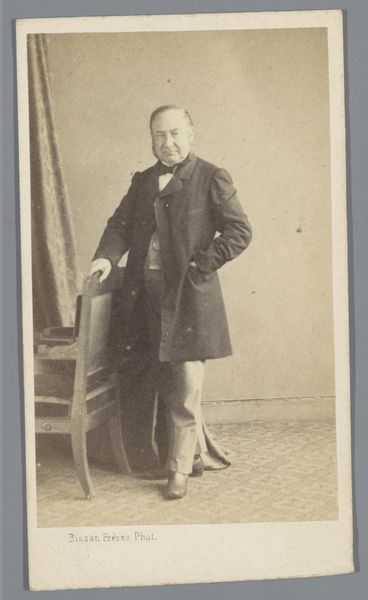

Editor: Here we have a photograph, "Portret van Ernest Picard, Frans staatsman en minister," by Carjat et Cie., dating from between 1862 and 1867. It feels so formal and posed. How do you interpret this work? Curator: Consider the material context: This is a photographic print, likely albumen, a process reliant on specific chemical compounds and paper. We should examine the resources required for this seemingly simple portrait – silver, egg whites, skilled labor to operate the cameras and process the image, each reflecting distinct social and economic forces. Editor: That's a different way of looking at it. I was focused on the man himself. Curator: But can we separate Picard, the politician, from the means of his visual representation? The act of creating this image, multiplied and distributed, shaped public perception. How does this compare to painted portraits that only the elite could access? This shift marks a transformation in visibility and power. Editor: So, you're saying that even a simple portrait can reveal a lot about society and its values at the time? Curator: Absolutely. And it’s essential to remember the darkroom, the photographer, and the entire infrastructure that made this image, and Picard's projection of power, possible. The photograph becomes a commodity, circulated and consumed. What stories do its materials tell? Editor: I see your point. I’ll never look at old portraits the same way again. Thank you. Curator: Indeed, it gives us pause to remember what has gone into producing even the simplest image.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.