drawing, paper, ink

#

drawing

#

medieval

#

landscape

#

paper

#

ink

#

cityscape

#

northern-renaissance

Dimensions: width 627 mm, height 444 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

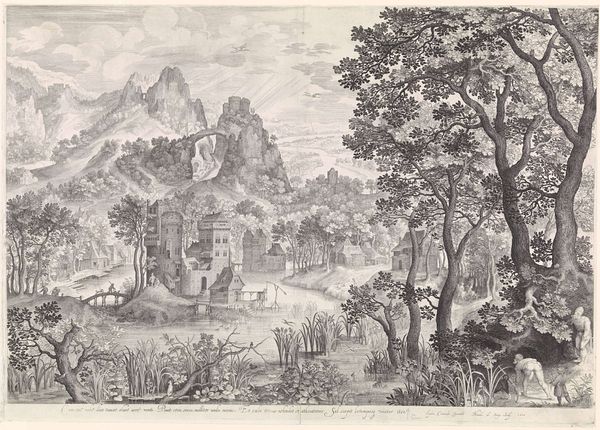

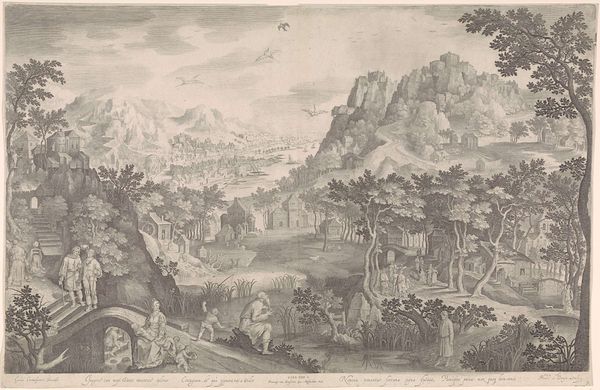

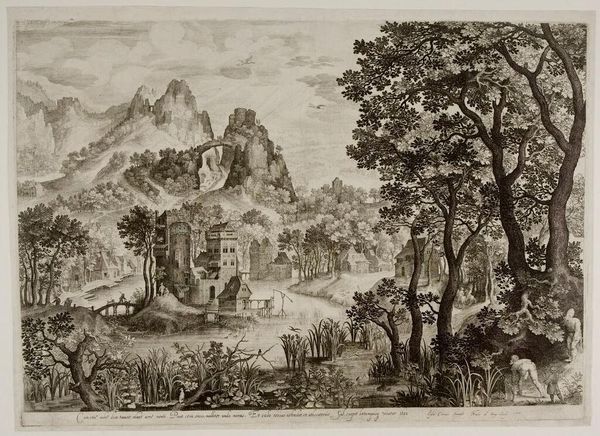

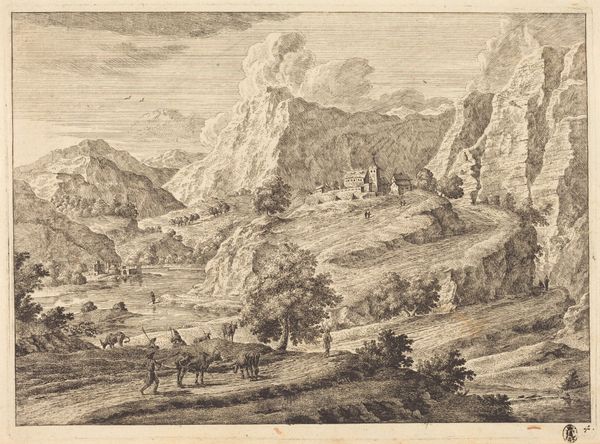

Curator: This drawing is titled "Landschap met eendenjacht", or "Landscape with Duck Hunt", dating roughly from 1600 to 1706. The anonymous artist used ink on paper to depict a panoramic landscape now held at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: My first impression is of a very meticulously crafted world. There is a crispness in the details, the artist certainly understood structure, the composition pulls you in towards that fantastical rocky bridge feature at the horizon. Curator: Absolutely, and I find it fascinating how this landscape embodies both the natural and the artificial. Note the labor involved in creating paper, the harvesting of materials for ink, then the skills and time dedicated to capturing every detail from those individual leaves to distant architectural features. It's a testament to human intervention shaping the world around them, echoed in the hunting scene in the bottom right corner, as people reshape it for their needs. Editor: The contrasts are certainly there: in the density of the foliage and the sharpness of the distant architecture; the rough, organic rendering of the trees, juxtaposed with the strict geometrical shapes of the buildings and landscape behind it. The medium itself—ink on paper—emphasizes line and form over color and texture. Curator: I agree, that attention to line, is particularly impressive when you think about this artwork, alongside of societal developments such as paper production. Ink was a precious commodity! These landscapes would have been commissioned, and affordable, to an increasingly bourgeoise population during the renaissance. Editor: Considering that the overall design follows established compositional formulas for landscapes during this period: The high vantage point offering that "all seeing" gaze and eye for spatial order—the landscape seems very much stylized. Curator: That makes me think how a piece like this speaks volumes about 17th century Dutch society, illustrating not just what people saw, but what they valued – an idealized and carefully controlled nature ripe for consumption. Editor: For me, the power resides within the framework, in the intricate arrangements and juxtapositions; ultimately it’s about line and form, an essential beauty revealed through careful consideration of its innate elements. Curator: Precisely, by looking beyond its intrinsic structure and at the making of the piece, we find how the means of production inform our understanding.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.