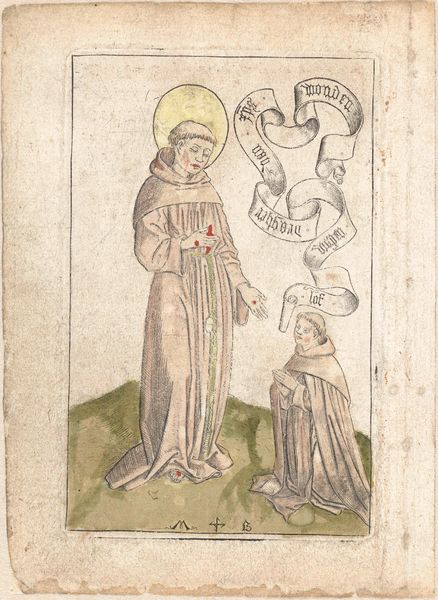

drawing, print

#

drawing

#

medieval

# print

#

figuration

#

history-painting

#

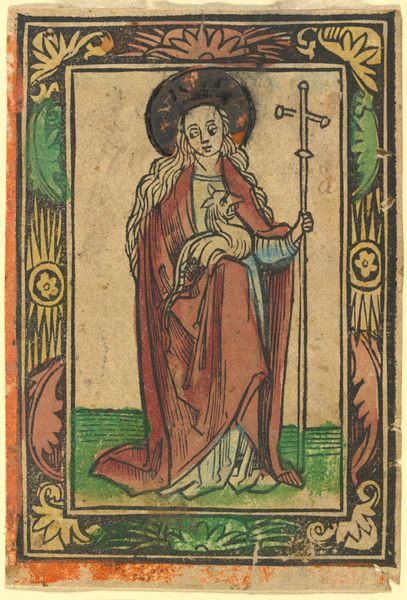

miniature

Dimensions: sheet: 7 1/2 x 4 13/16 in. (19.1 x 12.3 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: This miniature, "St. Nicolas of Myra," dates to the 15th century and resides here at the Met. Editor: My initial reaction is drawn to its intimate scale, the gentle, almost faded coloration and detailed border give the miniature a tender feel. What can you tell us about its materiality? Curator: It’s fascinating to consider the creation of this miniature print; an unknown hand skillfully made it with drawing, paint, and printing, quite possibly within a workshop. This challenges the modern divide between art and craft. Think about the labor involved in the meticulous printing, each color carefully applied to bring St. Nicholas to life. Editor: It’s equally fascinating to consider St. Nicholas himself within his historical and social context. He wasn't just a figure of religious reverence, but a symbol of charity and justice in a world grappling with immense inequalities. Who was he really serving with such visible wealth? Curator: Indeed. This small object was more than mere decoration; it facilitated devotion but also perpetuated power structures, shaping social beliefs and potentially reinforcing the Church's role in daily life. Consider the raw materials required—paper, ink, pigments—and their sourcing, which speaks volumes about trade networks and resource control at that time. Editor: And let's look closely at those objects. The three balls, or rather, one held here – they're often interpreted as symbols of wealth or charity; possibly representative of the story of St. Nicolas paying the debts of the three impoverished girls and saving them from sex work and allowing them to marry honorably. It serves as a crucial element that encourages a dialogue about gendered labor, historical marginalization, and religious intervention within medieval society. How far did his "charity" truly go, though, when he refused to critique structural oppression and social ills that left women vulnerable in the first place? Curator: Absolutely. When we consider that each artistic decision reflects an individual or workshop's knowledge, technical capabilities, and also what would have pleased their patron we gain richer understandings of social systems present within art. Editor: Analyzing art this way—examining it both in terms of its materiality and sociohistorical roots—enables us to better question art, culture, and historical narratives. Curator: Yes, it lets us go beyond the surface to investigate art’s creation, context, and cultural importance. Editor: Ultimately creating deeper, multifaceted insight to past social dynamics, artistic creation and even potentially influencing a re-examination of present day issues, such as economic inequity and human rights, issues Saint Nicolas might take exception to, even now.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.