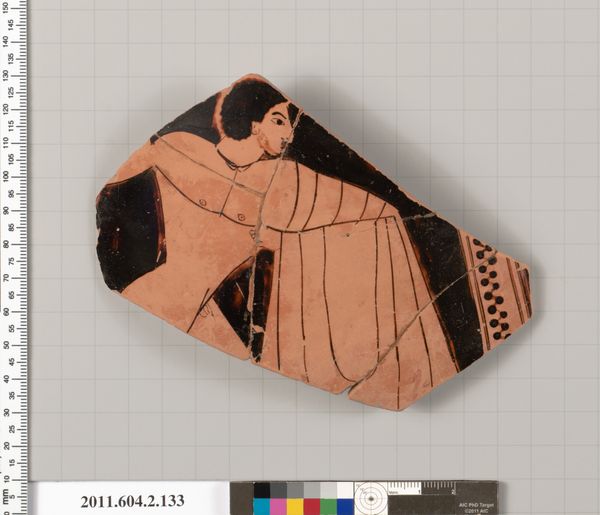

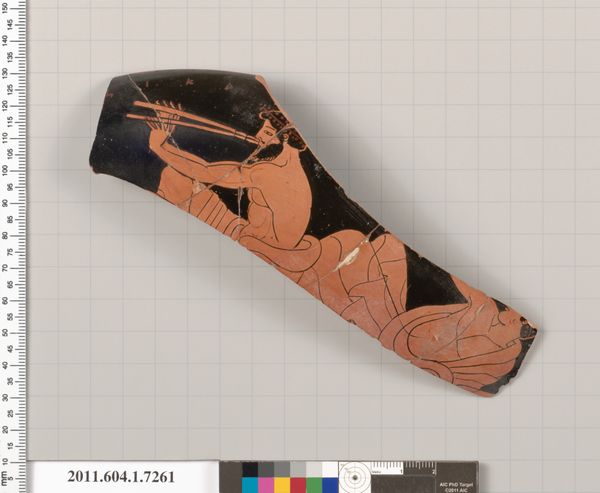

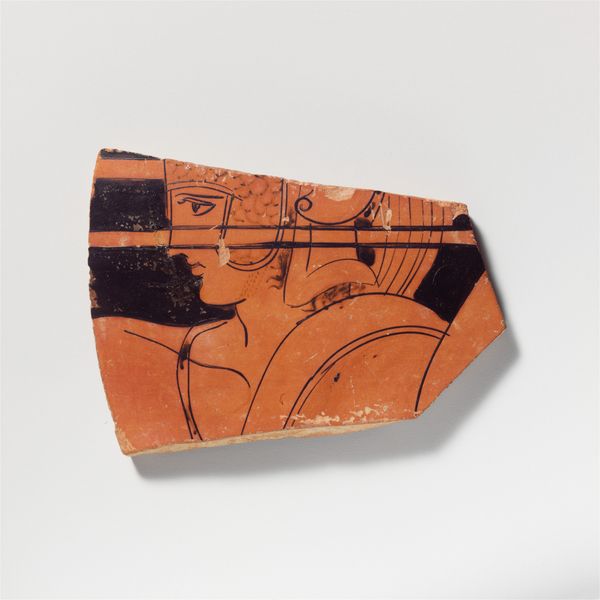

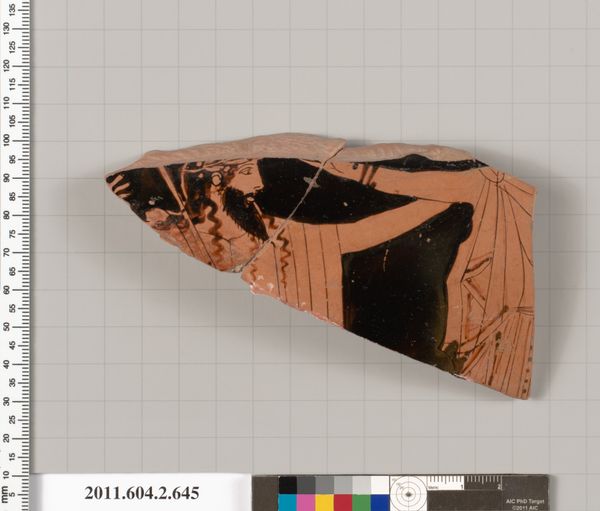

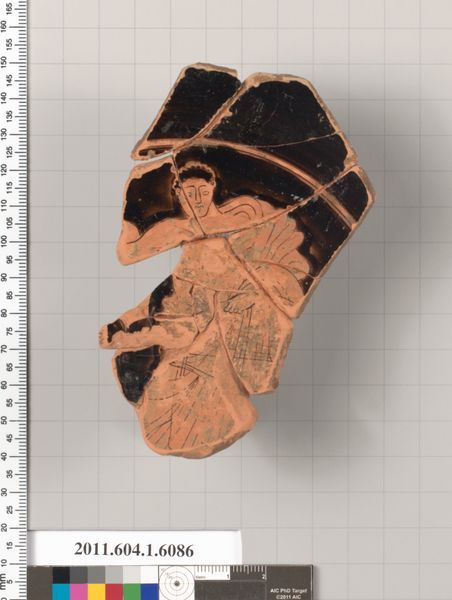

Terracotta fragment of a column-krater (bowl for mixing wine and water) 530 BC

0:00

0:00

drawing, ceramic, terracotta

#

drawing

#

greek-and-roman-art

#

landscape

#

ceramic

#

figuration

#

roman-art

#

ancient-mediterranean

#

terracotta

Copyright: Public Domain

Editor: We're looking at a terracotta fragment from what was once a column-krater, a bowl for mixing wine and water. It dates back to 530 BC and is currently housed at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The fragment has this beautiful reddish-orange hue contrasting with black figures, creating a powerful visual impact, despite its broken state. How do you interpret this work, particularly considering its historical context? Curator: This fragment speaks volumes, doesn't it? Look beyond just the image; think about its function. This wasn't simply decoration; the krater itself, used for communal drinking, was central to ancient Greek social and political life. Who was participating in these symposia? Who was excluded? The imagery depicted, now fragmented, likely offered narratives reinforcing societal norms. What stories do you think this scene, with its partial figures and geometric patterns, might have been trying to tell, and for whom? Editor: I hadn’t thought about the social dynamics tied to the object itself, just the figures. The fragment makes me consider the untold parts of the story, who is missing. Curator: Exactly! And consider the materiality: Terracotta itself signifies accessibility, compared to more precious materials. How might the democratization of art-making and ownership—even back then—challenge or reinforce existing power structures? Think about the role of craft versus 'high art.' Editor: So even a broken piece of pottery offers a lens into ancient social structures and power dynamics. It’s amazing to think of art not just as aesthetic, but deeply embedded in cultural and political contexts. Curator: Precisely! The act of examining art like this lets us reconstruct possible narratives. Art becomes an act of social archaeology.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.