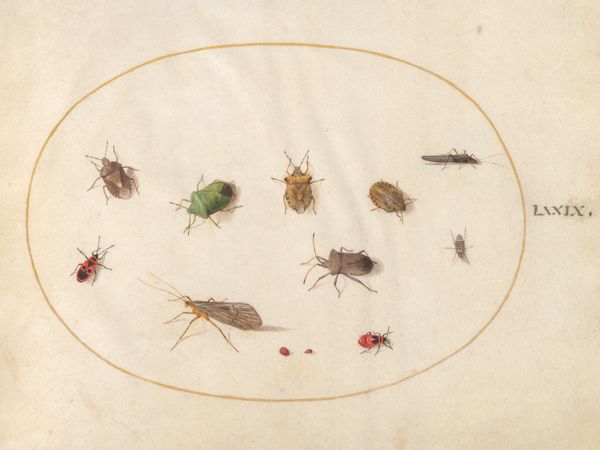

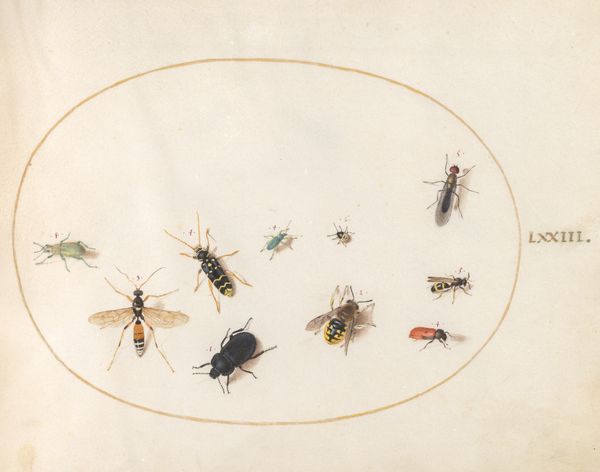

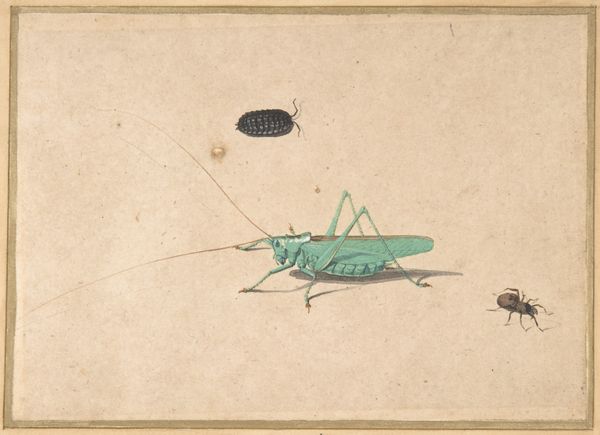

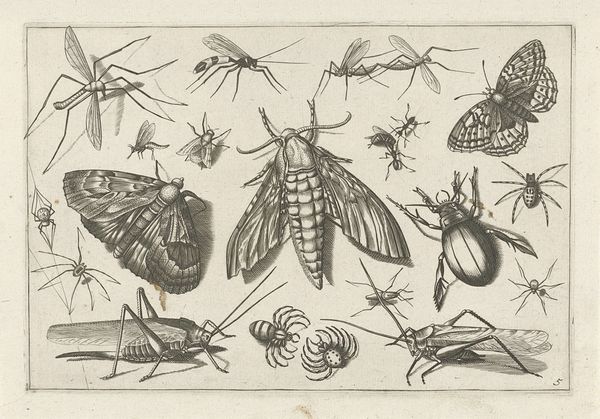

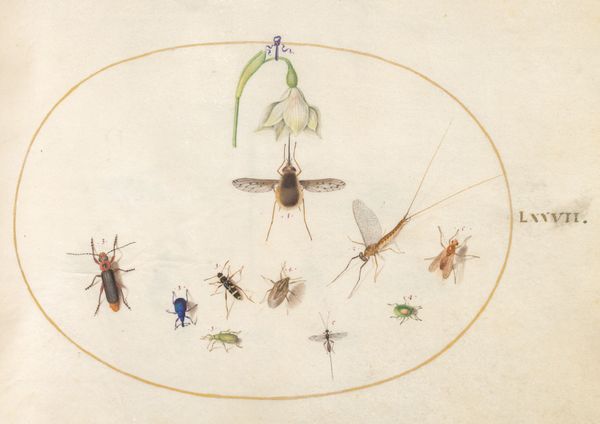

Plate 55: Aquatic Insects and Invertebrates, Including a Snail c. 1575 - 1580

0:00

0:00

drawing, watercolor

#

drawing

#

water colours

#

mannerism

#

11_renaissance

#

watercolor

Dimensions: page size (approximate): 14.3 x 18.4 cm (5 5/8 x 7 1/4 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

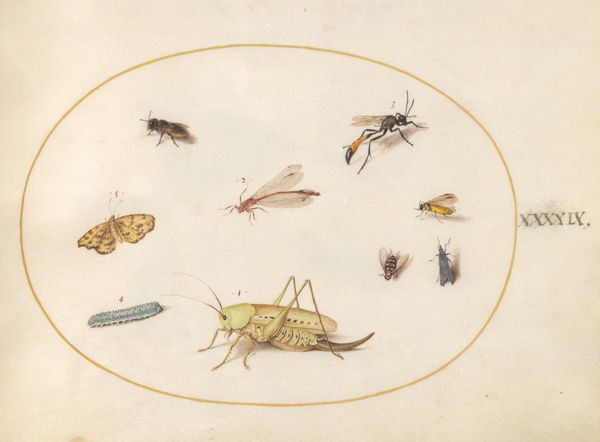

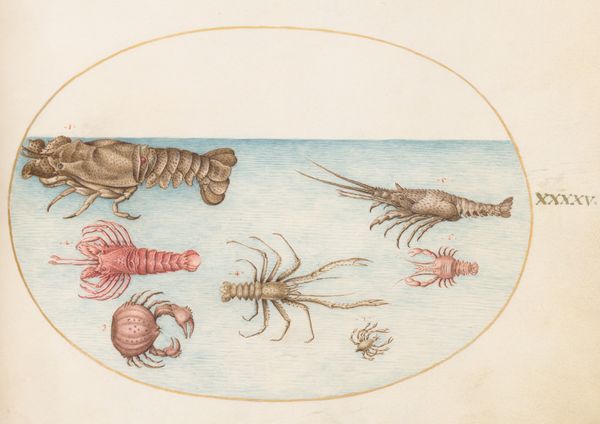

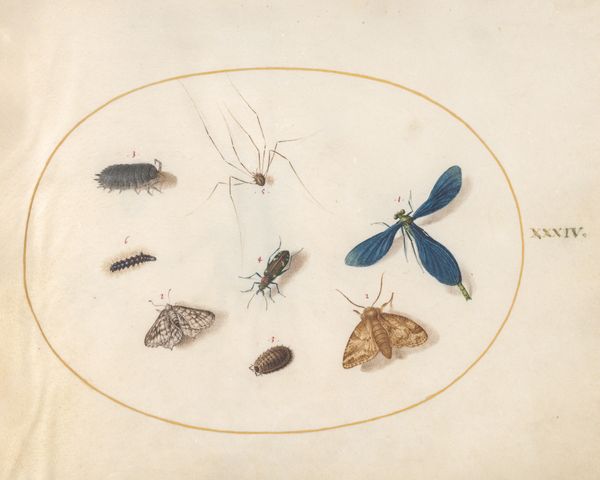

Editor: Joris Hoefnagel’s “Plate 55: Aquatic Insects and Invertebrates, Including a Snail," dating from around 1575 to 1580, presents this wonderfully rendered collection of creatures using watercolor. I find the almost scientific precision mixed with the slight abstraction of the water's surface intriguing. What do you see in this piece? Curator: What immediately strikes me is the collision of scientific observation and Mannerist aesthetics. Hoefnagel’s work functions as a kind of inventory of the natural world, aligning with the era’s burgeoning scientific curiosity. But it's equally important to consider what *isn't* being inventoried. Editor: What do you mean? Curator: Consider how the representation of these 'lesser' creatures speaks to a developing social hierarchy. These meticulous drawings simultaneously highlight the natural world's intricacies, and perhaps reinforce a sense of human dominance over it. How are these small animals positioned within a larger context of control and understanding of the world? Editor: I hadn’t considered that. It seems that art like this can reflect how people categorized and valued different parts of the world, not just the plants and animals but society itself. Curator: Exactly. And think about who had access to this kind of knowledge. This wasn’t accessible to everyone, right? Editor: No, definitely not. This was knowledge for a select, privileged group. It's a reflection of power, isn’t it? Curator: Precisely. Editor: It’s fascinating to think about how scientific illustration can be read through such a critical lens. I learned so much! Curator: Indeed! It allows us to examine the intersection of art, science, and social power dynamics during the Renaissance.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.