print, woodcut

#

portrait

#

narrative-art

# print

#

german-expressionism

#

figuration

#

expressionism

#

woodcut

#

monochrome

Copyright: Public Domain: Artvee

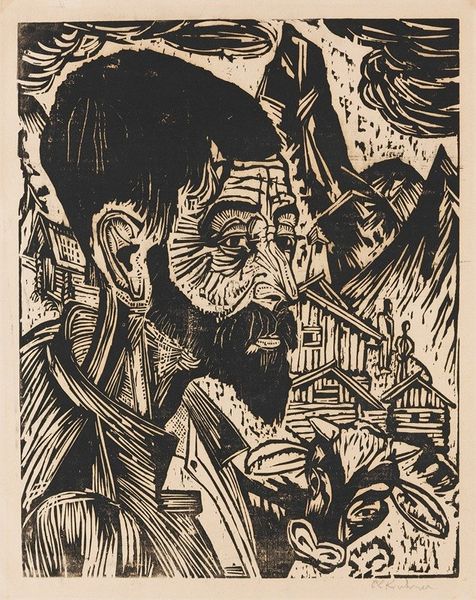

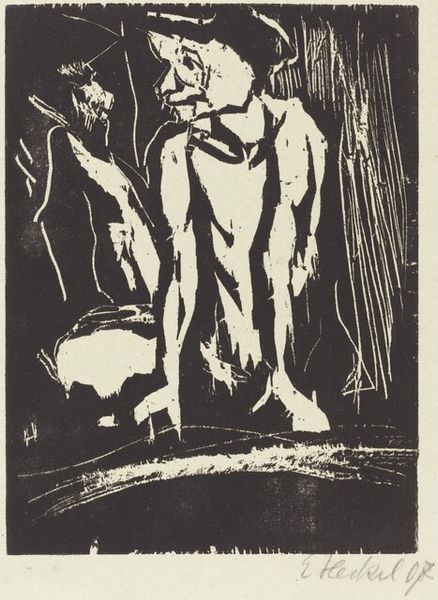

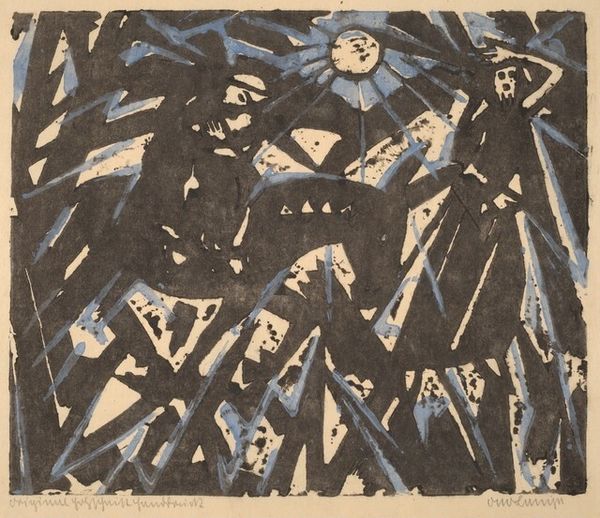

Editor: This is Ernst Ludwig Kirchner's "Mondnacht" from 1924. It's a woodcut print in black and white, and the starkness of the figures really strikes me. What draws your attention when you look at it? Curator: The radical simplicity of the woodcut, its reliance on stark contrasts of black and white, immediately speaks to the labor involved. This isn't about illusionism; it's about the direct impact of the tool on the material. Notice how the angularity of the cuts not only defines the figures, but also embodies a certain social unease. Editor: Social unease? I thought it might be more about a specific emotion, or a psychological state. Curator: Perhaps, but isn't the psychological inextricably linked to the social? Kirchner’s Expressionism is not solely an internal expression. The very process of woodcut, a readily available and affordable medium, places this work within a context of broader social production and accessibility. This was art for, and often by, a specific socio-economic strata. Editor: That's a perspective I hadn't considered. I was so focused on the visual impact, the expressiveness. Curator: And the visual impact is, of course, critical! The heavy reliance on black suggests a kind of obscuration, even alienation. It's a visual manifestation of a society grappling with industrialization and its discontents. The labour becomes both subject and means. The very materiality carries that social weight. Editor: So you’re saying even the *way* it's made tells a story about the time. Curator: Precisely. This woodcut serves as a tangible artifact, a record of both artistic creation and broader societal forces. A cultural product to be unpacked. Editor: I'll never look at a woodcut the same way again. This piece isn't just an image; it’s a statement. Curator: Indeed. Art provides evidence, but you need to learn how to read it, materially.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.