#

pen illustration

#

pen sketch

#

pencil sketch

#

old engraving style

#

personal sketchbook

#

pen-ink sketch

#

pen work

#

sketchbook drawing

#

sketchbook art

#

pencil art

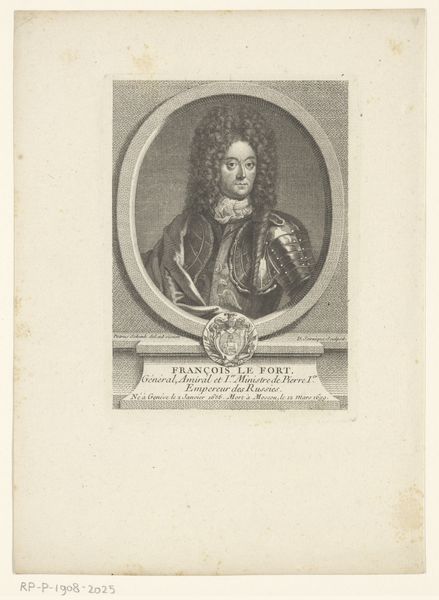

Dimensions: height 124 mm, width 78 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have a portrait of William III, Prince of Orange. It’s an engraving by James Fittler, dating roughly from 1758 to 1835, currently held here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: My first thought? It feels incredibly... labored. All those meticulously etched lines! It makes you aware of the sheer physical effort in producing this. Curator: Exactly. Think of the tools involved: the burin, the copperplate, the inks. Each impression pulled represents manual skill, a repeatable commodity, yet always carrying traces of the artisan. We should examine this piece less as high art and more as carefully reproduced labor, disseminated across prints for varied consumers. Editor: And disseminated with a very specific message, too. William III here is framed within symbols of power and authority - crowns, a crest with lions and unicorns...this isn't just a portrait; it’s political imagery intended to solidify his reign. Who would have consumed such prints and where would they have displayed them? Were these ubiquitous images of power, meant for wide distribution? Curator: Likely a mix. Its materiality speaks to broader print culture, where images proliferated through books and pamphlets shaping popular opinion, so availability played a large part in who and where it spread. Was it just wealthy royalists proudly adorning their parlors, or did tavern keepers subtly showcase their loyalty? Think of the cost to acquire such images, limiting initial circulation. Editor: A very calculated distribution indeed, perhaps fueling narratives in the service of maintaining political power through art in everyday life. Curator: Well said, the proliferation of printed portraits served specific purposes of power during the period. Editor: Ultimately this piece reminds us that an image isn't simply representational; it's enmeshed within a complex web of production, reception, and political maneuvering.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.