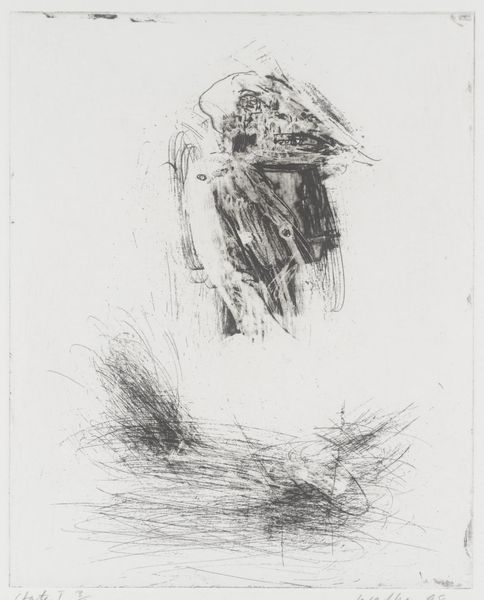

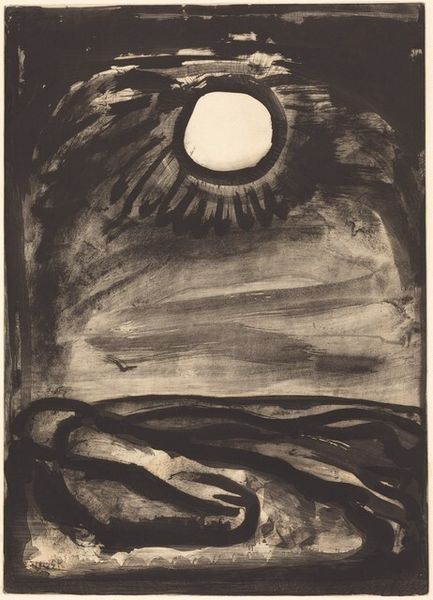

drawing, pencil

#

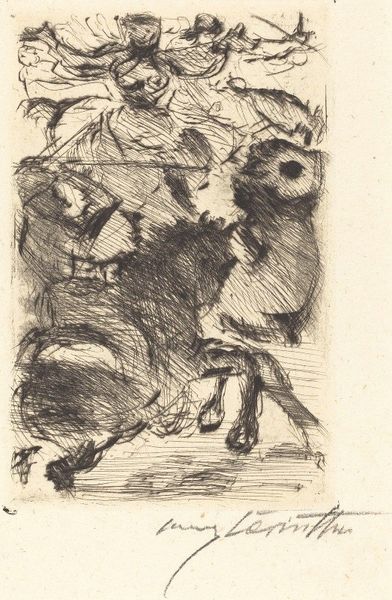

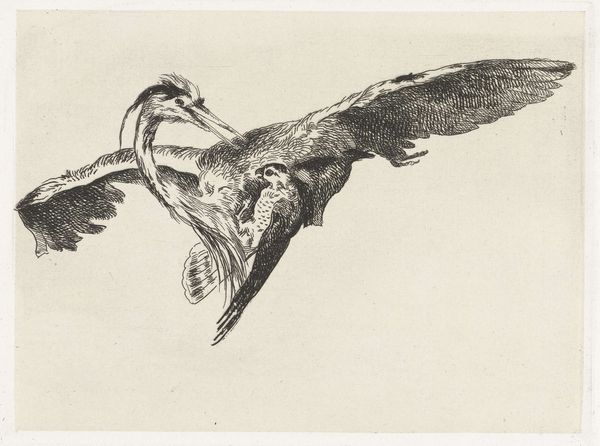

drawing

#

pencil drawing

#

pencil

#

abstraction

Dimensions: sheet: 22.54 × 30.48 cm (8 7/8 × 12 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

Editor: We’re looking at Ronald Bladen’s "Untitled (#27)," a pencil drawing from around 1946-47. It strikes me as almost apocalyptic – this intense darkness and a kind of roiling, undefined space. What’s your take on a piece like this, especially considering the time it was made? Curator: Well, the late 1940s were a period of intense societal reflection. World War II had just ended, leaving behind immense devastation and a questioning of established norms. The abstraction we see here, rather than depicting something concrete, could be read as a response to the anxieties of the time. Do you see any particular shapes or forms emerging in the drawing? Editor: There's this heavy, dark circle and what looks a bit like waves at the bottom, but everything is so blurred and uncertain. Is that intentional? Curator: Absolutely. Artists like Bladen were challenging the traditional role of art. Instead of representing reality, they explored inner states and societal upheavals. Think about the rise of existentialism during this period – a focus on individual experience and the search for meaning in a seemingly absurd world. Abstraction becomes a powerful tool for expressing these uncertainties. This wasn't just art for art's sake; it was a visual language for navigating a complex new world. Editor: So, the ambiguity is the point. It’s less about what it depicts and more about what it evokes about the society and anxieties of that era. Curator: Precisely. It pushes viewers to engage with their own feelings and interpretations within that post-war context, considering what was publicly acceptable or, maybe more appropriately, socially ignored. What do you think that ambiguity accomplishes? Editor: I guess it allows for individual experiences of trauma and uncertainty to be reflected upon rather than a unified public front that wasn’t really there. I’m starting to see how even abstract art can be deeply rooted in specific historical moments. Curator: Indeed. The political power of imagery should not be disregarded. It can create community, encourage action, and question social structures. A drawing like this becomes less an artistic statement and more a powerful message rooted in public sentiment. Editor: I hadn’t thought of it that way. It offers a totally different way to read abstract art. Thanks!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.