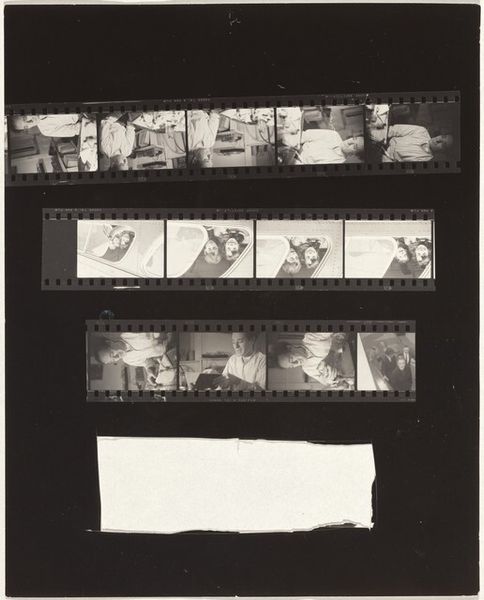

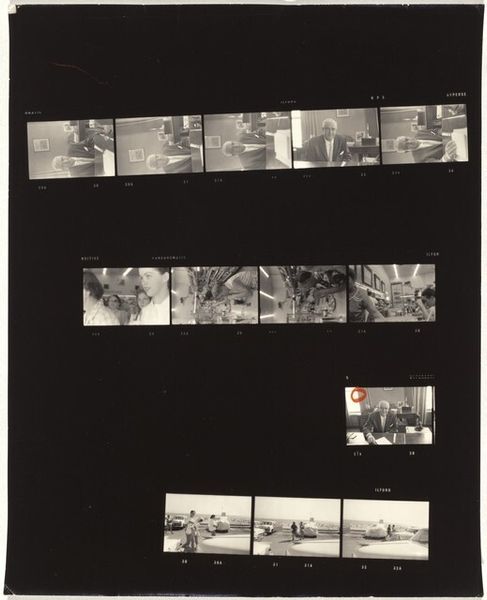

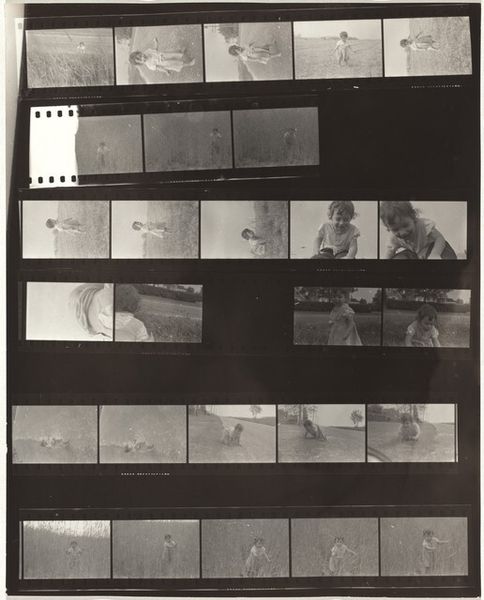

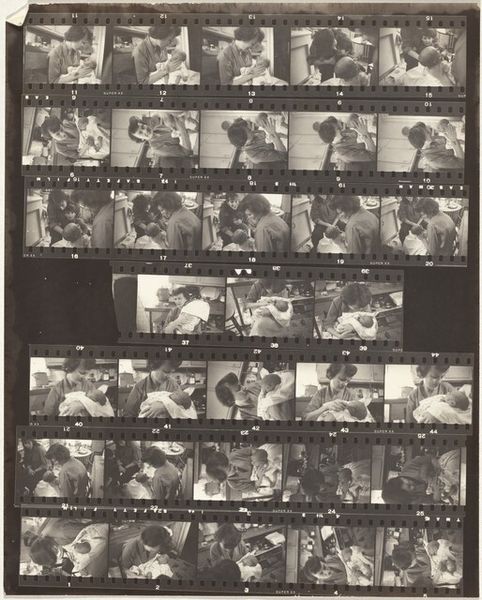

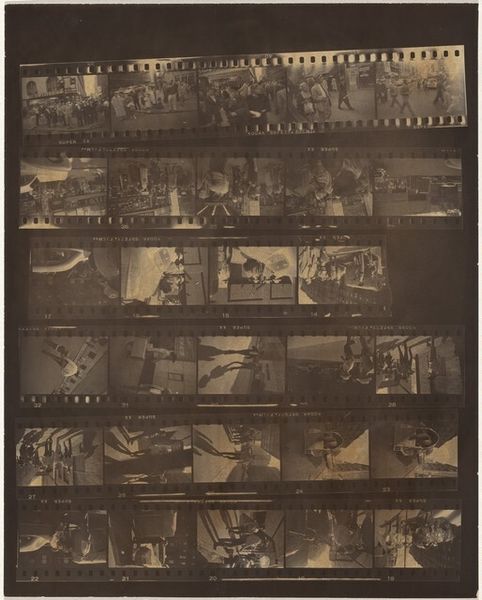

contact-print, photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

contact-print

#

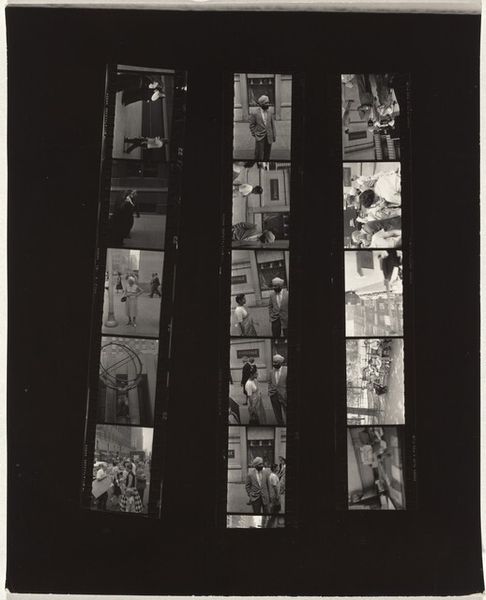

street-photography

#

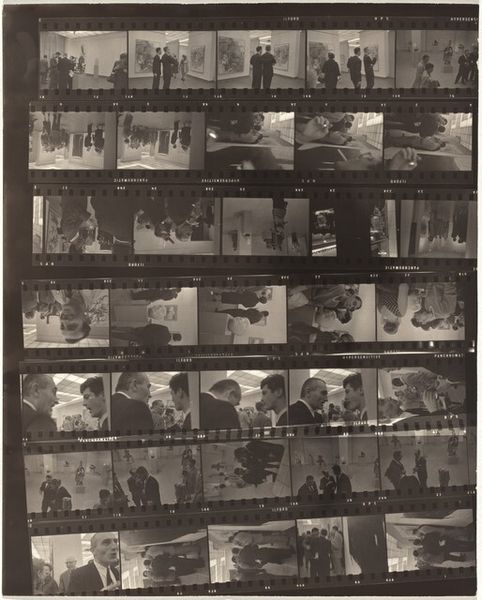

photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

ashcan-school

#

modernism

#

realism

Dimensions: overall: 25.3 x 20.4 cm (9 15/16 x 8 1/16 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

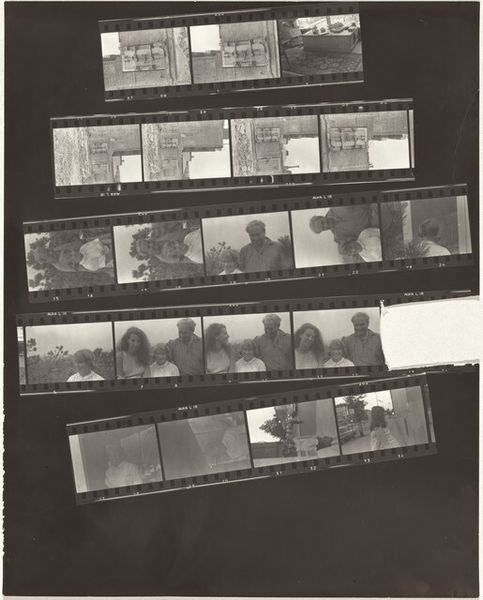

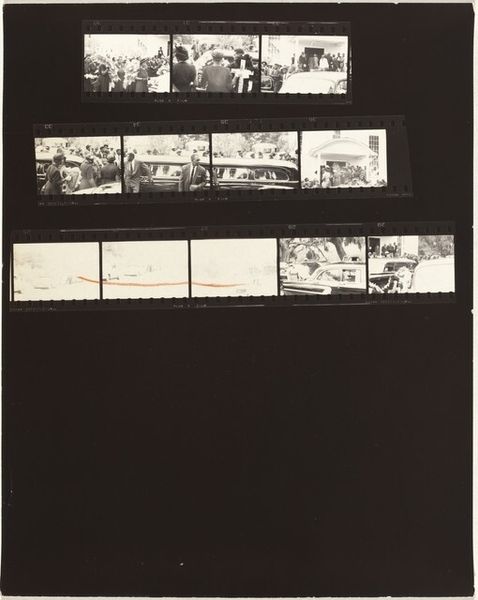

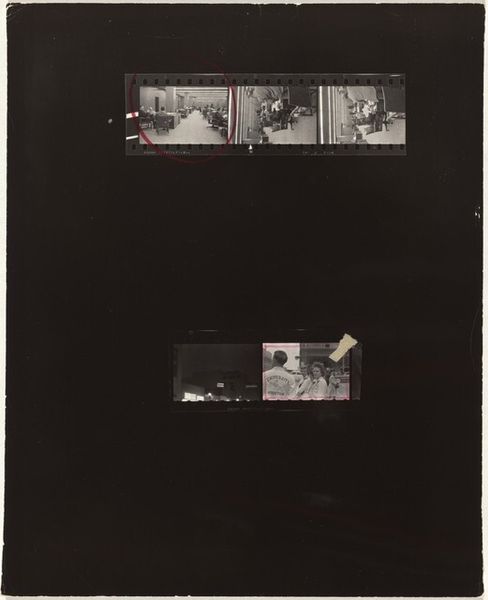

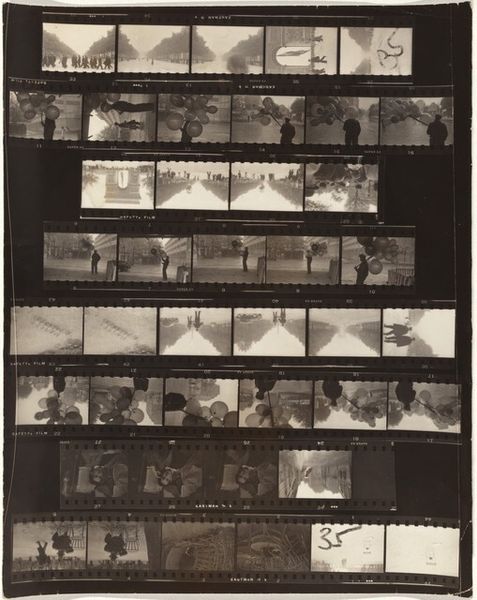

Curator: Today we’re examining a gelatin silver print by Robert Frank, made in 1955, titled "Guggenheim 350—Esso oil refinery, Baton Rouge, Louisiana." What are your initial impressions? Editor: My immediate feeling is one of disquiet. The high contrast and starkness make it feel almost like an autopsy report on industrial society. Curator: It’s fascinating you say that. Structurally, Frank’s work often challenges traditional composition, opting for a raw, unfiltered approach. Notice how the negative strip itself is the primary subject, the frames presented almost as fragmented evidence. Editor: Precisely. The fragmented frames amplify that sense of things being broken or disjointed. Oil refineries often symbolize progress and power, but the way Frank captures this scene seems to speak more to alienation. Curator: One could interpret the oil refinery itself as a modern-day Tower of Babel—a symbol of hubris. The Esso name is iconic, tied to energy and postwar prosperity, yet here it's presented on the contact sheet with mundane frames that reveal working stiffs and nothing iconic. Editor: Indeed. Frank consistently uses this kind of juxtaposition to expose social commentary. By placing images of workers, rather blankly staring, near this modern monument to industrial prowess, the frame invites reflection on their contributions—or rather, their subservience. Are they proud builders, or disposable tools? Curator: Furthermore, the high contrast in the print lends itself to an almost unbearable tension. There’s very little mid-tone; only blinding light or crushing darkness. The figures within seem trapped, like moths pinned to a board. Editor: And consider the black void encompassing the film strips. It's almost like these lives, these industrial sites, exist within a vast emptiness, questioning the true cost of such ‘progress.’ It’s heavy stuff. Curator: Absolutely. In revisiting this work, I'm reminded of how deeply embedded structural formalism is intertwined with iconographic weight. It's not just about shapes and contrasts; it's about decoding the anxieties of a nation through them. Editor: Ultimately, Frank offers more questions than answers, using symbols to evoke the anxieties simmering beneath the surface of 1950s America. He challenges viewers to face a sometimes brutal reality of industrial society, captured in something as simple as a contact print.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.