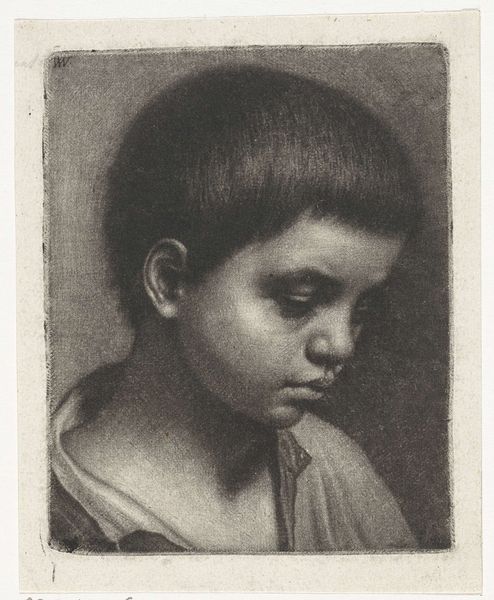

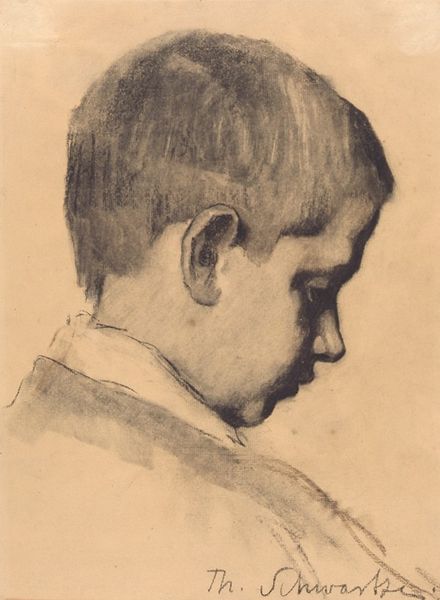

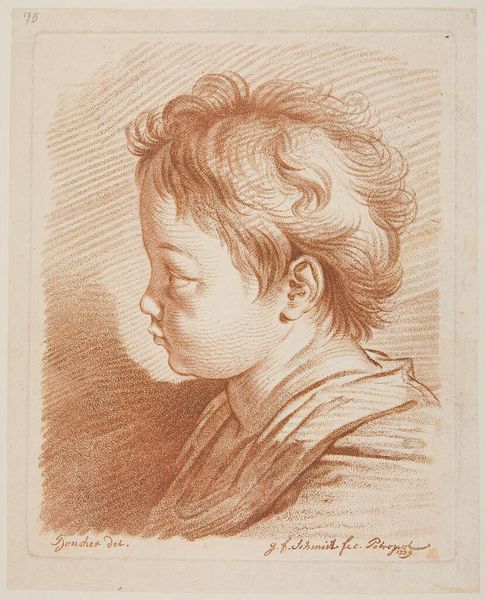

drawing, charcoal

#

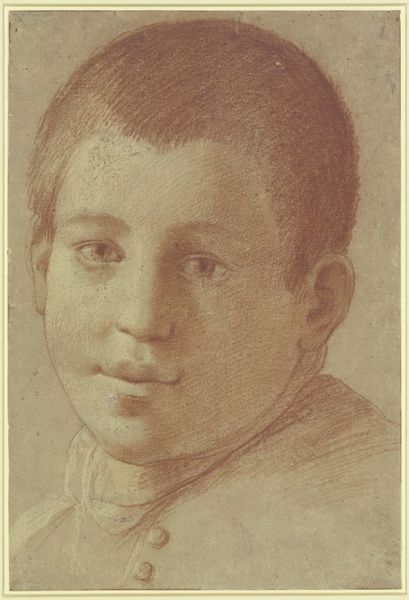

portrait

#

drawing

#

baroque

#

charcoal drawing

#

figuration

#

portrait drawing

#

charcoal

Dimensions: height 127 mm, width 97 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This captivating piece, "Hoofd van een jongen, naar rechts," or "Head of a Boy, facing right" is currently housed at the Rijksmuseum, made sometime between 1658 and 1727, though the artist remains unknown. The artist rendered the subject using charcoal in a precise drawing. What's your initial take? Editor: There's a pensive quality, a gravity to the young boy's expression. He almost looks burdened beyond his years. The artist captured such an intimate moment in what feels like a fleeting glimpse of real life. Curator: It’s intriguing that you see a sense of melancholy. Given the material - charcoal - there is something immediate and raw. What would this work have represented to audiences of the 17th and 18th centuries, do you think? The accessibility of the materials and the way in which the image captures the Baroque aesthetic certainly open avenues for questioning the definition of 'high art' at the time. Editor: Absolutely. Think about the social and cultural backdrop. Portraits, especially of the young and wealthy, often served as emblems of power and lineage, especially with the boom of artistic academies throughout Europe during the period in which this was created. Here, we have this work created at the intersection of a growing European economy deeply embedded in forced labor and resource extraction that further led to growing disparity. How were the lives of these kids displayed or not displayed, and in what ways might art depicting the most vulnerable, then and now, bring to question these societal realities? Curator: Your point is salient. Considering the historical context allows us to analyze the function of images during a period when Dutch wealth creation involved extensive global exploitation and extraction. It forces us to ponder who had the privilege of being portrayed and for what purpose. It’s equally crucial to remember the skill that lies behind crafting and popularizing the drawings; even sketches can capture an important and underrepresented history and materiality that other, more grandiose images lack. Editor: This work allows us to reflect on portraiture's societal implications beyond surface appearances, questioning notions of labor, value, representation, and whose stories are privileged within historical archives. This unknown artist might be asking the same. Curator: Precisely. Thinking through your framing helps bring those critical dimensions into the present. It challenges viewers to question who dictates which narratives are considered worth preserving and displaying in institutions like the Rijksmuseum.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.