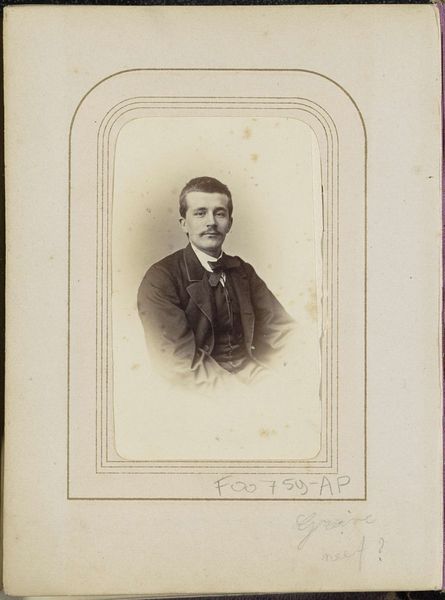

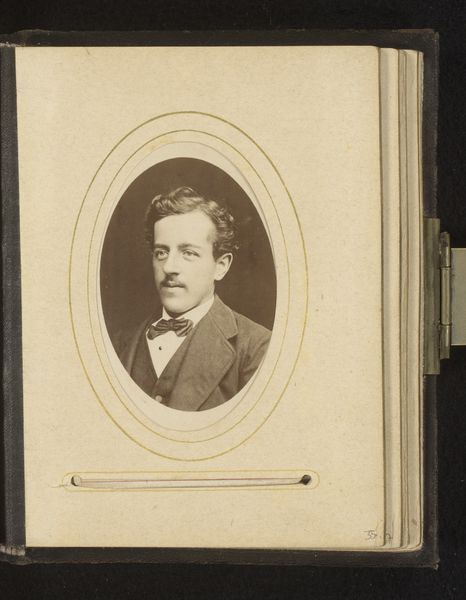

photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

portrait

#

photography

#

portrait reference

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

portrait art

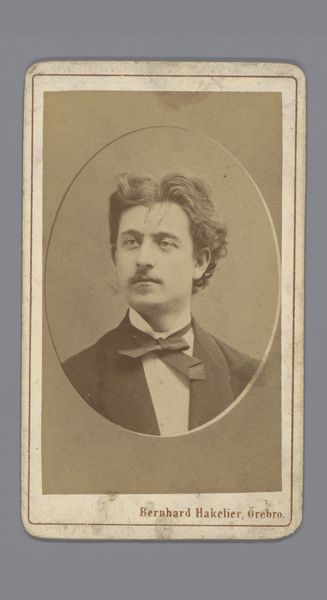

Dimensions: height 85 mm, width 51 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

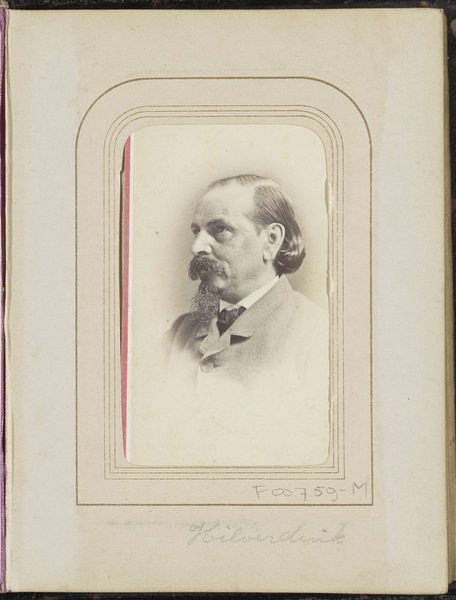

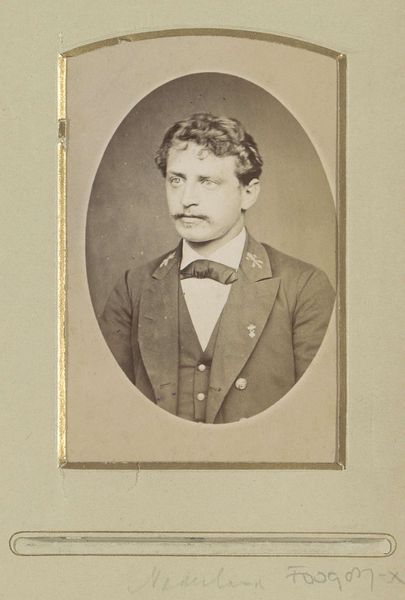

Curator: Here we have an intriguing portrait, "Portret van een man aangeduid als Hilverdink (zoon)," created sometime between 1863 and 1879. It's a gelatin-silver print, held in the collection of the Rijksmuseum, by Theodor Brüggemann. Editor: The sitter's intense gaze is compelling, and there’s almost a slight melancholy about his expression. It seems characteristic of early portrait photography and hints at the performance of Victorian masculinity. Curator: That performance is interesting. Early photography carried the symbolic weight of memorialization. These portraits acted as relics of a specific moment and were intended to convey more than just the person's likeness. His attire, the bow tie, is a marker of status but perhaps also of cultivated intelligence, or artistic sensibility. Editor: Agreed, the trappings speak volumes about class and aspiration. Though, I wonder what that era's performance of the ideal bourgeois masks or distorts in the individual’s identity. It seems less about authentic self-expression, and more about fitting the narrow confines of patriarchal expectation. This, to me, prompts a critique of that rigidity. Curator: The gaze itself holds secrets too, doesn't it? The eyes, the window to the soul as it were, were understood differently back then. Gazing directly into the lens became almost a statement. Also, notice the pose: classical in its conception, yet tempered with the softness afforded by the new medium of photography, as distinct from the formality of painted portraiture. Editor: But how complicit was someone like Brüggemann, operating within the commercial norms of the day, in perpetuating certain visual stereotypes about gender or class? I think it’s essential to unpack how photography—from its very beginnings—became a tool in visually encoding societal biases. The seemingly simple photographic project should not prevent an informed view of contemporary political interpretation. Curator: A potent consideration, absolutely. While the formal qualities capture a particular ideal of masculine identity of that time, looking deeper exposes a web of assumptions and coded meanings we can, from our contemporary perspective, interrogate and possibly subvert. I wonder, if Brüggemann foresaw us looking at his images 150 years later? Editor: These types of portraits invite questions, both historically and philosophically, about identity. Perhaps they were intended to offer the man a space to craft his legacy, and us to scrutinize those very constructions.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.