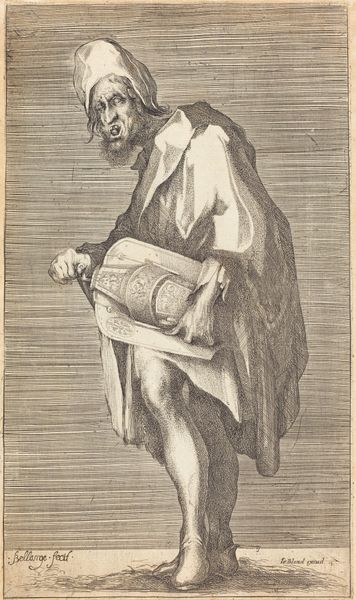

engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 164 mm, width 103 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This engraving from the early 1700s, titled “Borstbeeld van Democritus” by Arnold Houbraken, is held here at the Rijksmuseum. I’m drawn to its historical weight and the figure it portrays: Democritus, a pre-Socratic Greek philosopher known for his atomic theory, and especially known for laughing at the follies of the world. Editor: The first thing that strikes me is that almost unsettling smile; he appears gleeful and manic. Look at the very palpable use of line work, it looks quite expressive. The engraving manages to bring a dynamic feel to the supposed bust of a thinker, making you wonder, just who he might be mocking. Curator: The act of representing a philosopher, especially one known for his atomic theories and the material world, during the Baroque period says so much about the cultural currents. Houbraken wasn’t merely capturing a likeness; he was making a statement about knowledge, philosophy, and their place in society, right? Considering the rise of rationalism, the enlightenment and so forth. How the means of philosophy were circulating throughout society. Editor: Exactly. Houbraken’s choice of engraving, itself a reproductive technology, highlights the social life of images and their dispersal in that period. Engravings facilitated access to classical thought, extending the influence of figures like Democritus, even if the process, you know, was mediated through this specific artistic labor, this act of copying. I am left curious, by the ways that images of "great" figures were being replicated. Curator: I wonder about the audience as well. To what extent does a smiling Democritus in the Dutch Baroque period reflect a cultural and political attitude towards classical thought? What statements about free thinking or knowledge does this imagery convey during a period when Dutch society experiences internal divisions around theology? Editor: It makes you realize that engravings weren't just passive reproductions, but active agents in constructing knowledge, social identity and even political discourse. How are people making meaning from classical images. I find it is exciting in a world still heavily governed by craftsmanship and artistry, engravings open a new way of dispersing information. Curator: Looking at Houbraken’s "Democritus", reminds me of the necessity of interrogating the past to comprehend the present, and how the reproduction of images of classical antiquity continues to reshape and reaffirm perceptions of figures who are relevant in constructing identity, gender and power structures in art and in society. Editor: Right, and by paying attention to materials, circulation, and means of production, one is able to question how images function and influence, past and present.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.