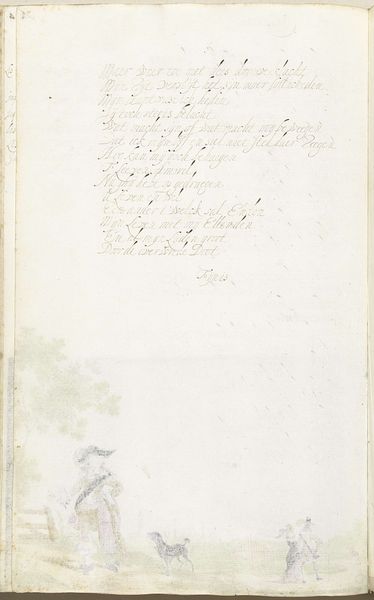

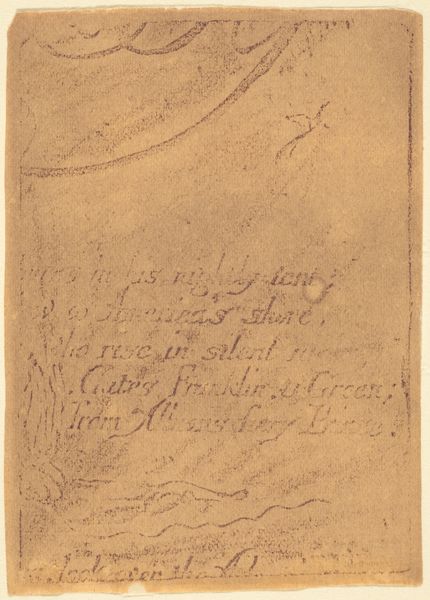

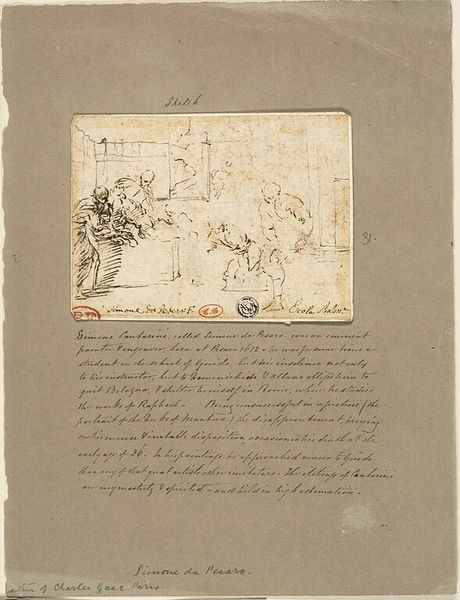

drawing, paper, ink, pencil

#

drawing

#

landscape

#

paper

#

ink

#

romanticism

#

pencil

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

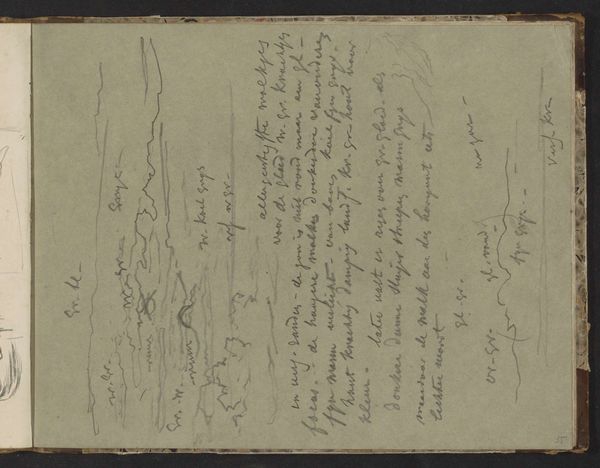

Curator: This evocative landscape drawing, "Heuvellandschap en twee patrijzen met jongen," or "Hill Landscape with Two Partridges and Chicks" by Johannes Tavenraat, dating from around 1833 to 1841, offers a quiet contemplation. It's rendered with pencil and ink on paper. What's your initial reaction? Editor: Well, initially it feels very intimate. I am immediately drawn to the rough texture of the paper, and how that intersects with the gestural lines, specifically around the depiction of the partridges. It reads almost like a personal, immediate document. Curator: Exactly. The medium, the accessibility and transportability of drawing materials like pencil and ink, suggests a direct relationship between the artist and the environment he seeks to capture. Think about the role of drawing within Romanticism—its connection to notions of self and of landscape as a space for individual experience and creation. Editor: It makes me consider how these images circulated. Was this drawing meant to be displayed as is? And how do questions of gender affect it. Was drawing deemed an activity of intellectual study or decorative leisure? Where in a domestic sphere would the drawing be viewed, by whom, and what purpose might it serve for them? The social currency, even if only domestic. Curator: Yes, the context of viewing definitely influences the experience, but what stands out to me are the artistic choices in creating the actual image—the weight of the lines, the negative space. Think about the physical action of the hand making the work. Note the quick, decisive marks creating a dynamic landscape—an almost immediate and direct physical link to the environment Tavenraat depicts. Editor: Right. So in essence we see layers upon layers of negotiation being expressed. We have questions around class and industry—around Tavenraat's economic conditions and relationship to both natural and synthetic sources, pencil and ink and the cost of paper—questions related to gender—its effects and place in Dutch society, for himself as a male and for the work he has left us, that ultimately affects the artwork itself. Curator: Absolutely. Understanding how the means and social nature of production shaped artistic outputs adds another layer to our understanding. Editor: Yes, it forces us to accept, and even champion, the limitations involved. That acceptance brings with it so much understanding. Curator: A beautiful demonstration of how thinking about materials and production impacts meaning and reception! Editor: Indeed, these kinds of objects become rich historical texts in this context.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.