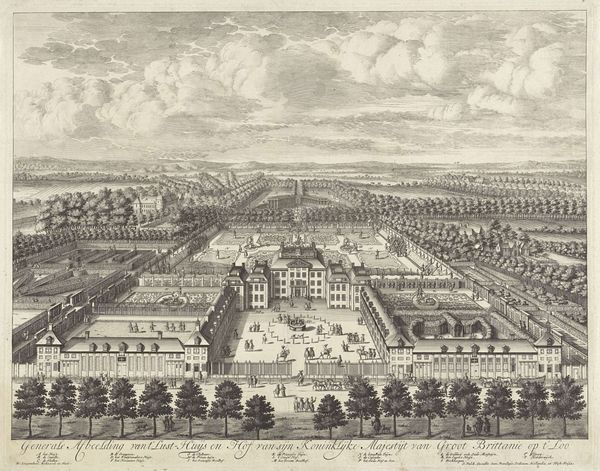

print, engraving

#

baroque

# print

#

old engraving style

#

landscape

#

cityscape

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 173 mm, width 207 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

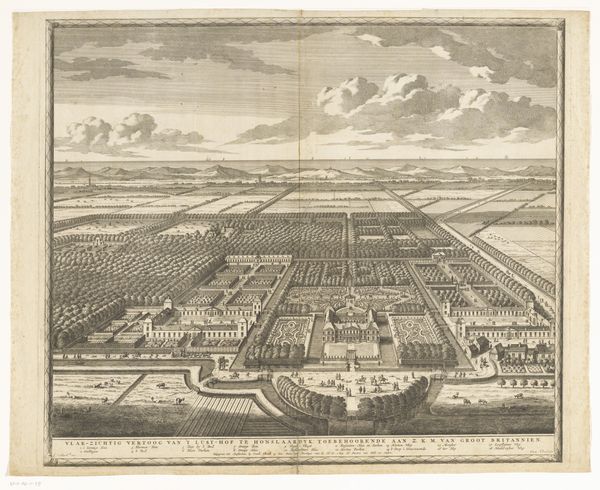

Curator: My first impression? Absolute power distilled into an image. It feels meticulously planned, a kind of… landscape-level exercise in control. Editor: Exactly! We're looking at "Gezicht op Paleis Het Loo in vogelvlucht," a bird's-eye view of Het Loo Palace created between 1689 and 1702. It’s an engraving, showcasing the Baroque obsession with order and dominance through landscape. Curator: The precision is mesmerizing, almost sterile. Those gardens—geometric patterns repeating into infinity! There’s something both beautiful and deeply unsettling about it. Is this art, or is it architectural propaganda? Editor: It's both, of course. The artist, Laurens Scherm, wasn't just capturing a pretty scene. This image projects a carefully constructed message about William III's reign, particularly focusing on his control and ability to govern the natural world – a crucial aspect of kingship during this era. Notice how the gardens literally radiate outwards from the palace? Power flows outwards. Curator: Like the veins of some benevolent—or perhaps not so benevolent—organism. It makes me wonder, what’s *not* shown here? What's hidden in the periphery that this "perfect" view conveniently obscures? The human cost, maybe? Editor: Precisely. Baroque art often masked social inequalities with grand displays of wealth and authority. The sheer labor required to construct and maintain these gardens, the unequal distribution of resources... These engravings were circulated amongst a particular elite, reinforcing their existing world view. Who benefitted? Who paid the price? Curator: The composition directs the eye inexorably towards the palace, almost like a spell. It’s so different from wandering in an actual garden. It has lost that wild quality I seek in nature; I think I am missing the poetry of wandering, but finding myself constrained in this print. Editor: And consider the medium: engraving. The crisp lines, the contrast of dark and light, speak to a desire for permanence and the power of reproduction. This wasn't a fleeting sketch, but a deliberate statement, reproduced for wide distribution and lasting impact. The Rijksmuseum currently holds it; it becomes like a powerful artifact in our current social, cultural and political landscape, making us consider its position between propaganda, history and memory. Curator: So much art of the time becomes a lens for interrogating authority now. After viewing the piece this way, what once felt superficially pristine now resonates with deeper socio-political reverberations, and I feel empowered. Editor: Exactly. Understanding the historical and social context transforms our experience, allowing us to confront, rather than simply consume, these complex visual legacies.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.