#

portrait

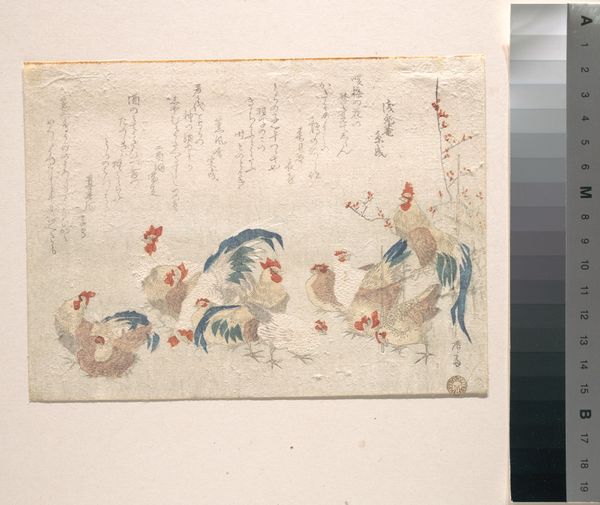

# print

#

asian-art

#

landscape

#

ukiyo-e

#

figuration

Dimensions: 8 5/16 x 7 7/16 in. (21.1 x 18.9 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

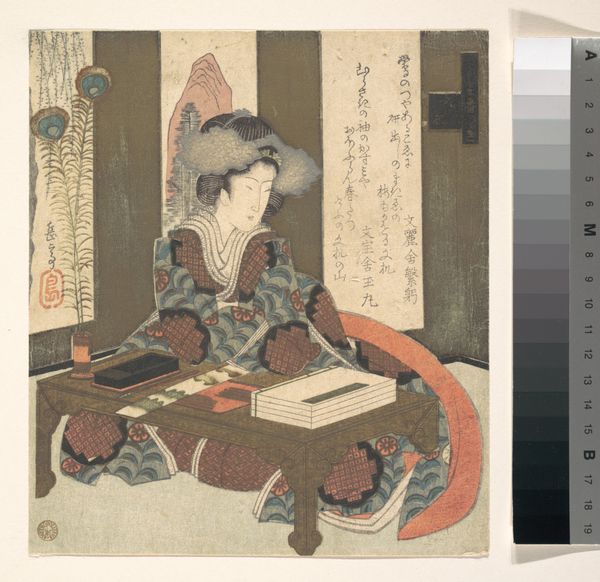

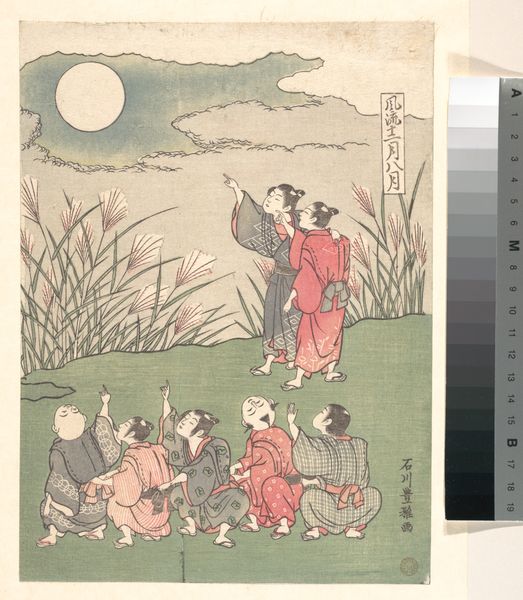

Editor: We’re looking at Yashima Gakutei's "Print," created between 1820 and 1840. It’s a ukiyo-e style print, housed here at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. There are a lot of things happening; a figure with a fan, waves, the moon, and text. How do you interpret this work? Curator: I see a powerful intersection of cultural references, suggesting a commentary on femininity and nature. This piece pulls from several loaded traditions: the image of the woman immediately recalls geisha culture, bound as it was with complex social expectations, and placed in a space punctuated by natural forces that are traditionally feminized. But she is more than just that tradition. How do you feel the traditional art forms function within a more contemporary understanding of feminism? Editor: I hadn’t thought of it like that, it felt very classical, not necessarily radical. Curator: And what do you see in that interplay? Consider how the inclusion of landscape elements -- waves, moon, cherry blossoms -- connects her image to ideas about the cyclical nature of life and, perhaps, even the ephemeral nature of beauty and power in a patriarchal society. Notice too how the inscription almost merges with the image of the cherry blossoms. Editor: So the artist is potentially making a statement about the role of women? The cherry blossom connection to text almost makes me feel like they're connected; the voice of women connected to a certain cultural idea of beauty that has almost no room for them as full people? Curator: Exactly. And how that connection resonates or chafes against your own experiences or understandings, now. Does understanding its cultural context influence your reception of the piece, especially when considering your experience and background? Editor: It does. Before, I saw a pretty picture. Now I'm thinking about what it means to be a woman represented in art, both then and now. Curator: Art history, for me, is about those connections, those resonances, those ruptures. Seeing how the past speaks – and doesn't speak – to the present.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.