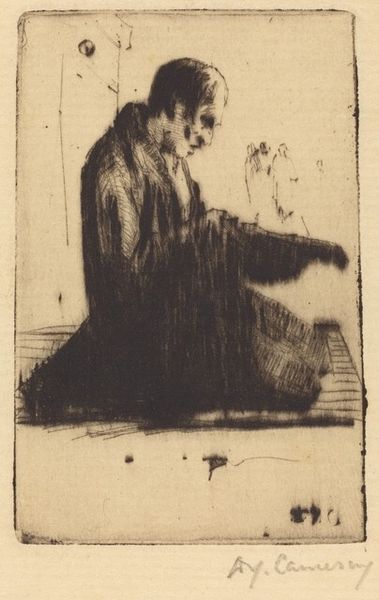

Dimensions: plate: 13 × 10 cm (5 1/8 × 3 15/16 in.) sheet: 23.3 × 22.5 cm (9 3/16 × 8 7/8 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

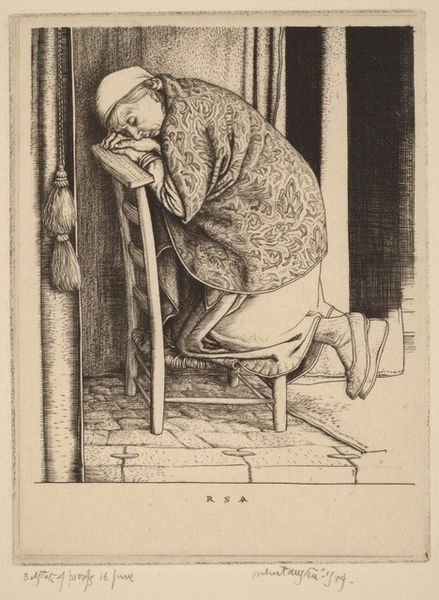

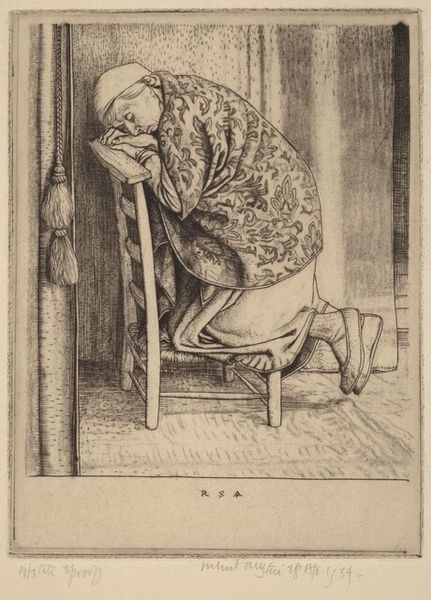

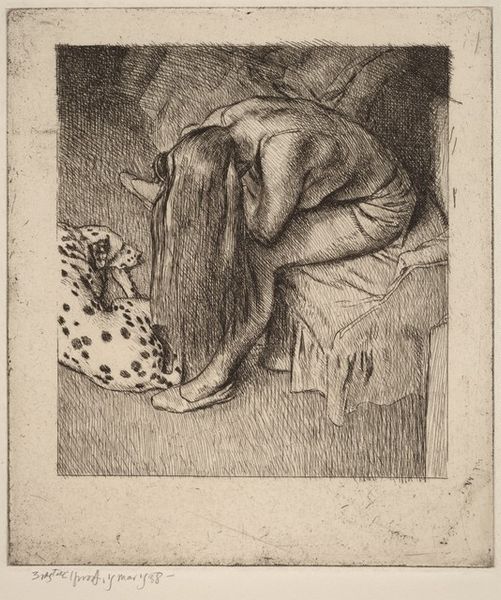

Curator: This intimate print by Robert Austin, entitled "Young Mother," dates to 1936. It's an etching, a medium that lends itself so well to detailed narratives like this one. My immediate response is one of hushed reverence, would you agree? The light feels subdued, focused inward. Editor: Absolutely. The scene feels both incredibly private and staged somehow. There's a density to the shading, almost claustrophobic. It draws all our attention to the mother and the unseen child in the cot. Curator: Right, the perspective definitely frames the maternal experience as central. We see her almost from behind, kneeling reverently as though at an altar, with that wonderful drape of cloth forming a sweeping curve reminiscent of classical depictions of mourning. The visual language hints at both sorrow and hope, echoing the cultural weight of motherhood. Editor: Indeed. Etchings in the interwar years held a particular cultural currency. Prints were relatively accessible, bringing fine art into middle-class homes. I wonder about the market for this work; how many “young mothers” were able to actually purchase a portrait of idealized motherhood during the depression era? And further, did they see themselves reflected in it? Curator: That's a crucial point, about who is the 'intended audience', as it complicates its visual message. The cot, for instance, almost feels like a prop, slightly removed from a purely realistic depiction. Is it the artist romanticizing an archetype, rather than reflecting actual, lived experiences of motherhood? The symbolic register is definitely operating here, it reminds us of similar themes from centuries before. Editor: There’s something carefully constructed about it that undercuts any sense of spontaneous sentiment. Also, it seems worth noting, depictions of motherhood, idealized or otherwise, served a significant role in shaping gender roles and expectations, particularly during the first half of the 20th century. Austin’s print enters that very fraught visual field, consciously or otherwise. Curator: Yes, there is definitely an element of instruction, too. In an interesting paradox the universal aspects become so visible it brings the particulars into sharp relief. What can we say we see now we stand back for a second viewing? Editor: For me, it reveals how artists often reflect and, even inadvertently, perpetuate societal expectations even when appearing to capture quiet, intimate moments. And that’s powerful and lasting, I think. Curator: I’ll echo that—seeing how seemingly gentle imagery encodes history can change how we look at the art of our time.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.