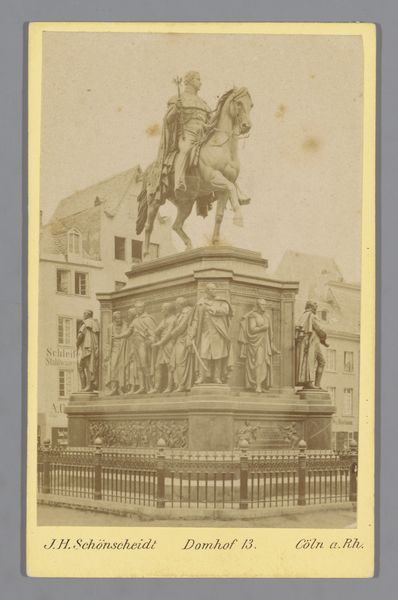

Dimensions: height 97 mm, width 64 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

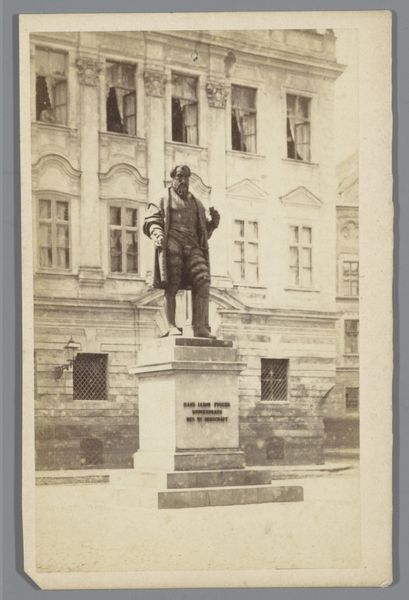

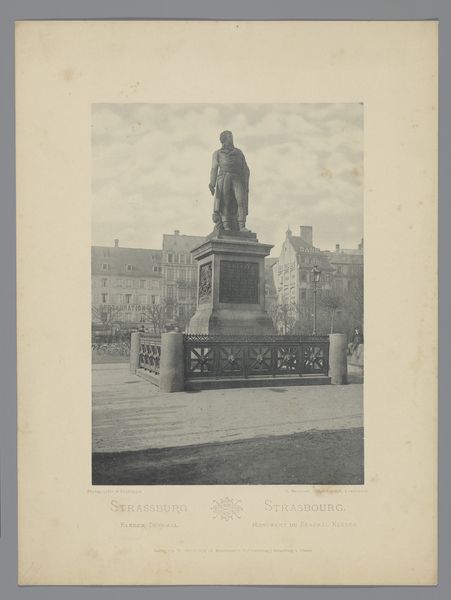

Curator: Here we have a photograph depicting the "Standbeeld van Schiller in Frankfurt am Main," a monument rendered in bronze. Though the precise date of the photograph remains unknown, the sculpture itself was erected sometime between 1860 and 1875. The artistry suggests a strong neoclassical influence. Editor: My first impression is its stark formality; it is imbued with a kind of sober dignity that seems typical for tributes dedicated to intellectuals during this period. There’s something about its greyscale, capturing the patina of time that further underlines that air of historic gravitas. Curator: That sense of dignity is precisely what sculptors aimed for during that period. They sought to create a legacy, crafting enduring images meant to shape the perception of historical figures in the public's mind. How better than the eternal medium of bronze? Statues like this became central to civic identity, embodying shared cultural values and even national aspirations. Editor: I'm curious though, what does it really mean to monumentalize someone? And how do we negotiate Schiller's complicated relationship to ideas of nationhood? He existed, of course, during a fractured German-speaking world long before Germany's unification. How does this image work to co-opt or perhaps re-frame the meanings behind his literary project? Is there a cost for converting revolutionary thought into statuary? Curator: Those are important questions, especially when considered through the lens of political imagery. Erecting such a statue in a public space wasn't just an aesthetic choice; it was a declaration of cultural and political alignment. Neoclassical sculptures of this kind were typically commissioned by governing elites, city councils, or patriotic societies that aimed to foster a particular sense of collective identity. Editor: Indeed. These images become a site of ongoing negotiation around identity, around whose contributions are valued, and how narratives are visually promoted over time. It compels us to constantly re-evaluate how history is told and by whom, while ensuring that alternative viewpoints aren’t silenced or erased. Curator: A monument, then, becomes less of a static object and more of an active participant in cultural and political discourse. Editor: Precisely, and the presence of a camera at the moment of its creation also introduces additional questions. For one, we could inquire into who funded its production. More simply, what kinds of gazes was this object intended to meet, both within Germany and abroad?

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.