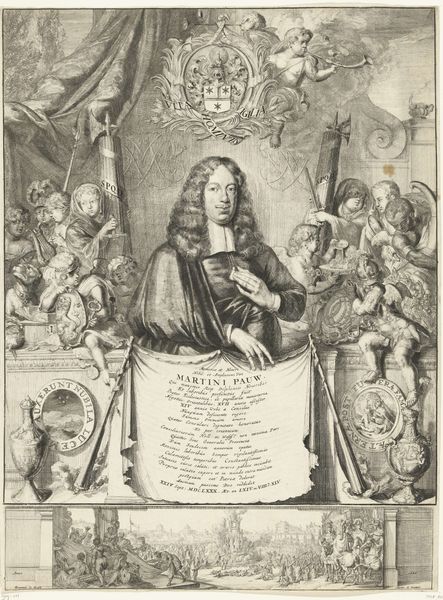

print, intaglio, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

# print

#

intaglio

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 389 mm, width 298 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This is a print entitled "Portret van Christina, koningin van Zweden," or "Portrait of Christina, Queen of Sweden," dating roughly between 1616 and 1657, credited to Paulus Pontius. It’s currently held in the Rijksmuseum. Editor: The density of the line work is the first thing I notice – it's incredibly detailed for an engraving. The amount of labor that went into this must have been immense. Curator: Absolutely. Consider the social context, too. Queen Christina was a fascinating figure—a powerful woman in a time of great upheaval. She ultimately abdicated her throne and converted to Catholicism, a highly controversial move for the time. The portrait has all these layers, right down to the Latin inscription meaning "Whither the fates call, virtue safely follows." Editor: Which speaks directly to power, the production of symbolic meaning. This print, likely reproduced multiple times, would have circulated as a commodity itself, reinforcing Christina’s image and, in effect, bolstering a whole social order dependent on producing such materials. What type of metal was used? How long did the process take? Were there specialized workshops involved? Curator: Indeed, each aspect of the image acts almost as a propaganda piece; the inclusion of both a figure with helmet and spear, perhaps meant to be the God Mars and a radiant Apollonian male on either side, framing Queen Christina's image. She's not simply presented, she's mythologized. How might these classical references be viewed through a postcolonial lens, considering Sweden’s historical involvement in various conflicts? Editor: That's what strikes me, too—how the materiality and method reflect a system deeply embedded in notions of hierarchy and power. I’m left pondering the tension between the intention of those Baroque engravers and what such portraits signify now. Curator: Seeing this portrait has reminded me that images are never neutral; they actively shape how we perceive history and individuals. Editor: Yes, and the means of production itself leaves traces of those systems—both intended and unintended.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.