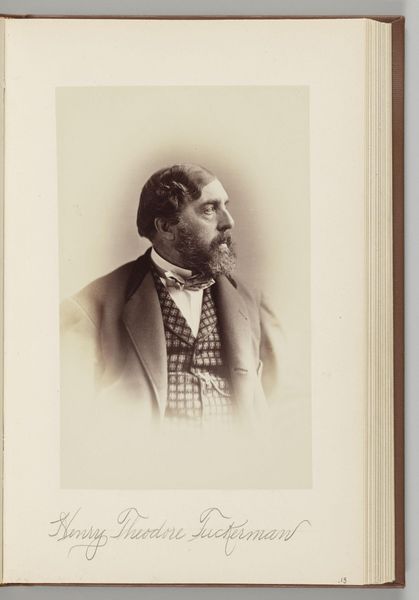

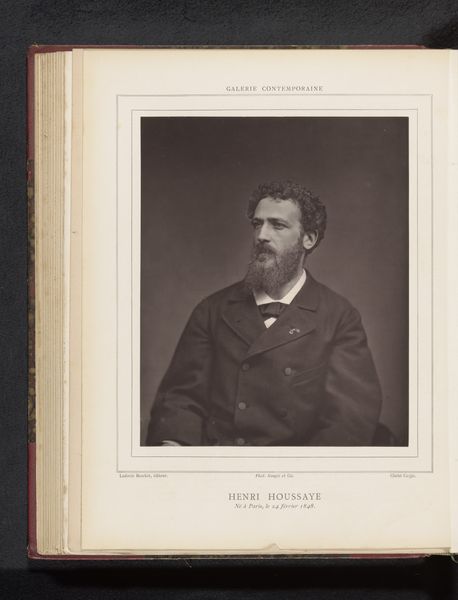

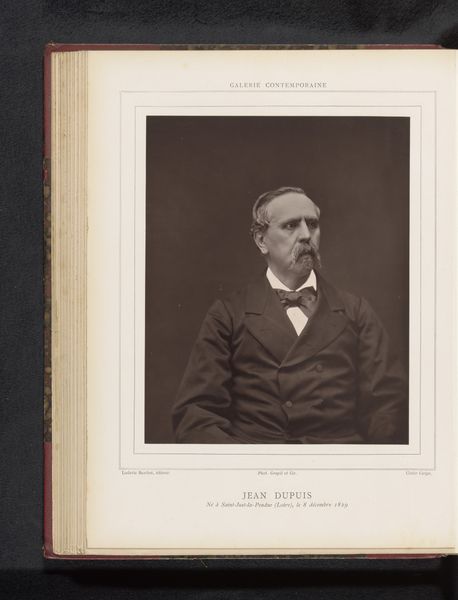

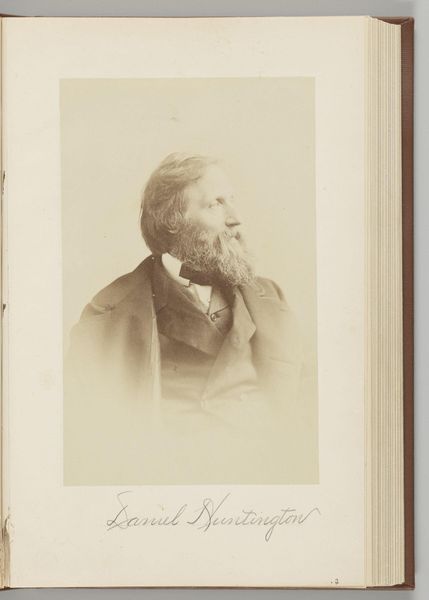

photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

portrait

#

photography

#

historical photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

19th century

Dimensions: height 232 mm, width 187 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

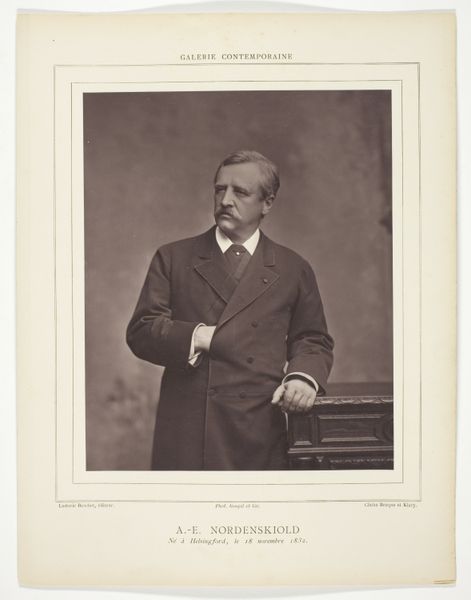

Curator: Here at the Rijksmuseum, we have "Portret van Eugène Spuller" by Etienne Carjat, captured before 1880, a gelatin-silver print offering a glimpse into the 19th century. Editor: It strikes me immediately how posed yet introspective it feels. He's clearly facing something, but there’s a quiet resolve in his expression. It almost hints at a narrative. Curator: Carjat, known for his portraits of prominent figures, certainly understood the power of image. Spuller was a notable politician, and Carjat likely intended to convey a sense of his authority. The controlled lighting, the formal attire—all serve to create a specific persona for public consumption. Editor: I wonder how much Spuller had a hand in crafting that persona? It's not just a picture; it is a representation of power. Thinking about how marginalized communities at that time lacked such representational agency really contextualizes the privilege embedded in this seemingly straightforward image. Curator: Absolutely. These portraits helped to solidify the social and political power structures. Access to photography and its distribution was highly controlled. Museums play a critical role here, we should carefully contextualize who gets remembered and how. Editor: Looking at his confident pose, I feel the stark absence of other voices and perspectives from that era. Acknowledging that absence becomes crucial. We must avoid unintentionally perpetuating a biased view of history through these images. Curator: Indeed, by engaging with these absences, we create a more complete, complex, and equitable picture of history. It calls for a continuous process of critical examination and active efforts to amplify previously marginalized voices. Editor: Right, it is about responsibly interrogating our inherited histories, to become actively anti-racist, feminist and to address these imbalances. It becomes not just about understanding the artwork, but also actively understanding the history of the world surrounding this artwork. Curator: Well said. Understanding portraits like this gives us insight not only into the individuals, but into how entire power structures and ideas were projected and upheld in their time, which shapes so much still. Editor: Right! So that the next time someone sees a similar work they have the critical framework to reflect on the values embedded in our historical institutions, collections, and modes of representation.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.