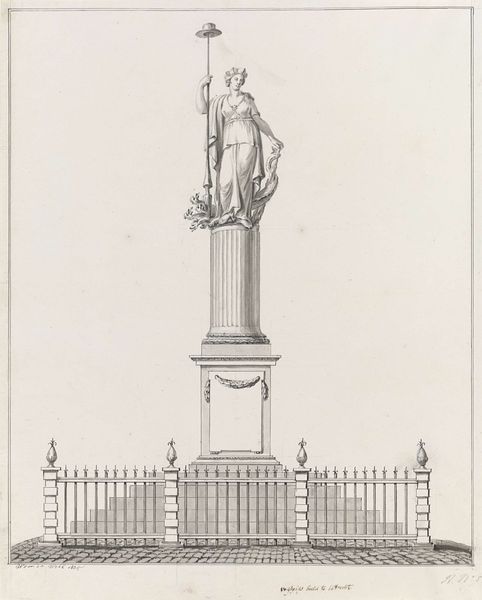

drawing, metal, sculpture, pencil, architecture

#

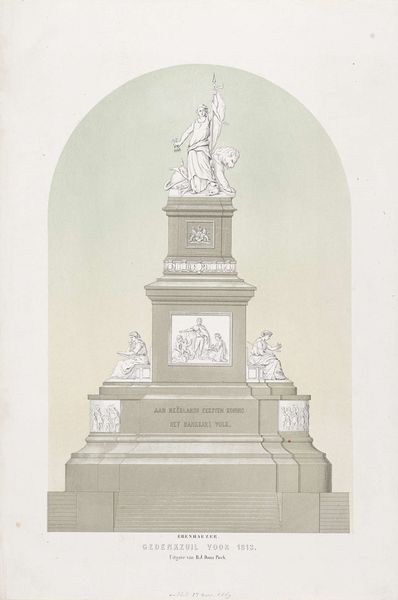

drawing

#

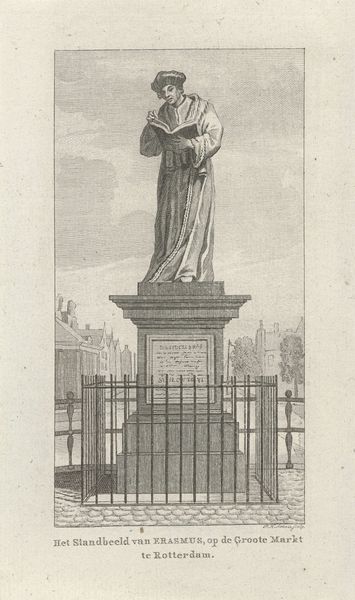

statue

#

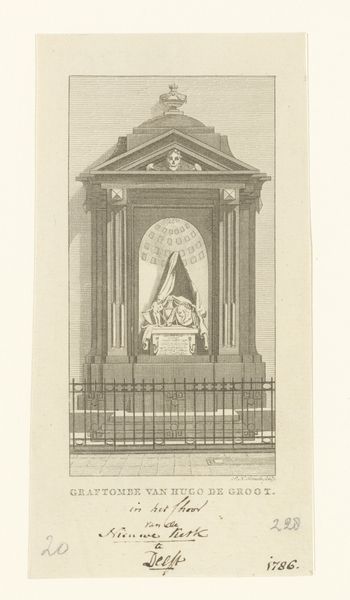

metal

#

pencil sketch

#

etching

#

sculpture

#

pencil

#

architecture drawing

#

cityscape

#

architecture

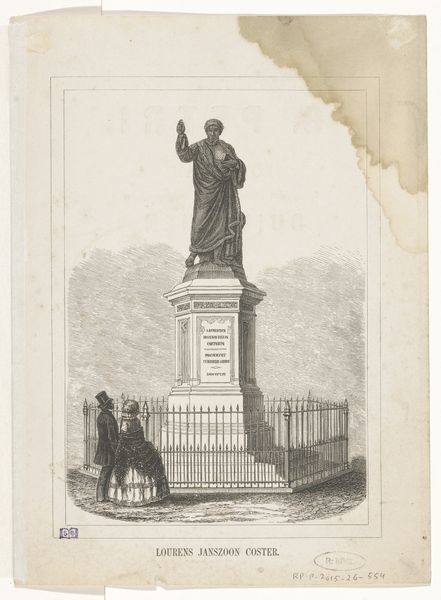

Dimensions: height 240 mm, width 160 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: This drawing, “Standbeeld van Coster in Haarlem, 1856" by Charles Binger, captures a statue in incredible detail using what looks like pencil and maybe some etching. It’s interesting how a relatively simple drawing conveys a sense of monumentality. What story does this image tell you? Curator: Well, immediately, it speaks to the power of public monuments in the 19th century and how they shaped civic identity. The statue itself, enclosed by a fence, becomes a focal point for civic pride, or at least, an approved narrative. I wonder, who was Coster, and what role did the monument play in Haarlem's social and political landscape at the time? Editor: From what I remember, Laurens Janszoon Coster is considered by some to be the inventor of printing in the Netherlands, although that's debated. Curator: Exactly. So, this statue isn't just about honoring an individual. It's about solidifying a national narrative, asserting cultural importance, and perhaps even subtly engaging in the ongoing debates around national identity and technological advancement. The location, the public square, is itself a stage for this performance of memory. Notice how the drawing elevates the statue and puts it on display. The fence, instead of distancing, highlights the role of the state, or city in this case, safeguarding its heroes. How do you think the medium of drawing affects how we perceive this monument today? Editor: I guess the drawing, by its very nature, seems less imposing than a photograph might. It’s like a gentle suggestion of civic pride, rather than a forceful declaration. Curator: Precisely. And it invites us to consider the layers of mediation – the original monument, the artist’s interpretation, and our own understanding filtered through the lens of history and evolving cultural values. Editor: It’s fascinating how much a simple drawing can reveal about public memory and civic identity. Curator: Indeed. And it underscores the power of art to shape not just our visual landscape but our understanding of history itself.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.