sculpture, marble

#

portrait

#

neoclacissism

#

sculpture

#

figuration

#

sculpture

#

mythology

#

marble

#

nude

Copyright: Public domain

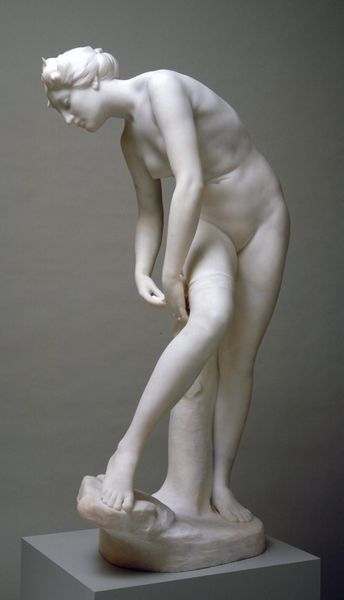

Curator: Let's spend a few minutes with Antonio Canova’s “Eurydice,” crafted in 1776. The sculpture embodies the Neoclassical style, meticulously rendered in marble. Editor: She’s ethereal, isn’t she? There's a profound sense of vulnerability in the upward gaze, the outstretched arm—a plea for connection. The rough-hewn rock supporting her creates a stark contrast with the smoothness of her skin, really accentuating the loss. Curator: Indeed. Canova's technical skill is undeniable. Look at the way he captures the textures of the marble, so evocative, creating an emotional charge that goes far beyond the object's surface. The sculpture participates in a much broader story about how the cultural elite wanted to picture Antiquity at that precise historical conjuncture. Editor: It's hard to disassociate it from the myth itself—Eurydice, forever just out of reach. Her nudity feels so… exposed, even in this stylized form. Curator: Well, nudity in Neoclassical sculpture was deployed, mostly, in reference to Ancient statuary. Remember, this piece comes right before the French Revolution and, even more importantly, just after Winckelmann had published his fundamental texts and research about the classical world. Editor: Still, viewing it today, one can't help but consider how female bodies have been perpetually subjected to the male gaze throughout art history and museology. What power dynamics are we unwittingly re-entrenching when we celebrate sculptures like these without providing space for historical nuance? Curator: Those conversations are crucial and continue to be actively explored through academic discourses, as well as outreach activities across museums and cultural venues around the world. What is relevant in the Neoclassical rediscovery of the classical world, as far as Canova is concerned, is his ambition to be compared to the ancient masters. Editor: It’s definitely a captivating—though not unproblematic—piece. Makes one think about what is seen, but, importantly, about what is *not* seen. Curator: It’s an invitation to think about how cultural productions reflect particular social and historical projects, especially in relationship to display mechanisms and art circuits.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.