print, engraving

#

narrative-art

# print

#

old engraving style

#

mannerism

#

figuration

#

history-painting

#

engraving

#

realism

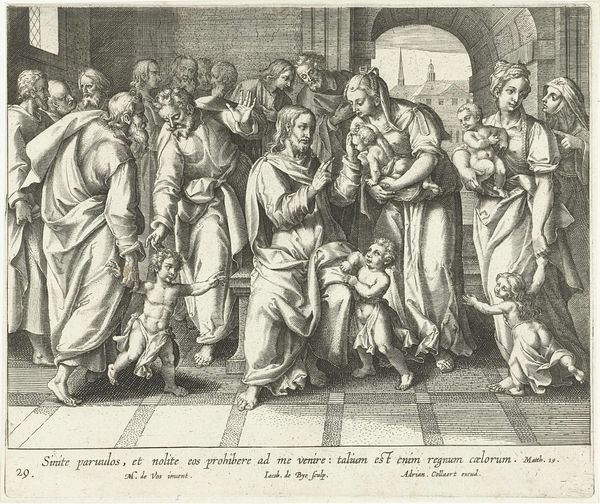

Dimensions: height 204 mm, width 264 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Let's consider this engraving titled "Mozes' beproeving bij de farao", dating from 1550 to 1625, currently residing here at the Rijksmuseum. It's attributed to Pieter Jalhea Furnius. Editor: It strikes me immediately as incredibly balanced. The composition feels deliberate, with the figures arranged almost symmetrically around the central scene of the child reaching toward something on a pedestal. There's a very palpable sense of restrained drama, even in the stillness of the figures. Curator: Absolutely. Note the precise execution of the engraving technique itself. The fine lines create variations in light and shadow. But it's worth considering that printmaking during this era involved a collaborative production line, so ascribing authorship solely to Furnius masks a complex history of labor. Editor: Indeed, the line work creates form. The way the engraver used hatching and cross-hatching to define volume, particularly in the drapery, is impressive. Observe how those long robes cascade; it guides our eye through the scene. It's like a visual symphony orchestrated through line and shadow. Curator: The materiality here also speaks volumes, or more specifically of access. Prints enabled wider audiences to experience these scenes. Engravings like these circulated narratives beyond elite circles, molding perceptions. So how was Furnius using his skills, and perhaps more critically, for whom was he laboring? Editor: And yet the success of that dissemination relies on the clarity and impact of the visual language itself. Semiotics would emphasize how these poses, the architecture, the attributes, all signify power, innocence, choice. It allows this drama, in that instance the presentation to the Pharaoh, to be absorbed from afar. Curator: Right, but beyond semiotics, we should think about the economic systems that sustained printmaking, about how artists negotiated patronage and the open market. Editor: Ultimately, both perspectives allow one to view how lines and economic conditions worked, with skill, to create visual dramas like that within “Mozes’ beproeving bij de farao”. Curator: Exactly, by questioning who truly made these pieces we add to our current interpretations, so very good point.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.