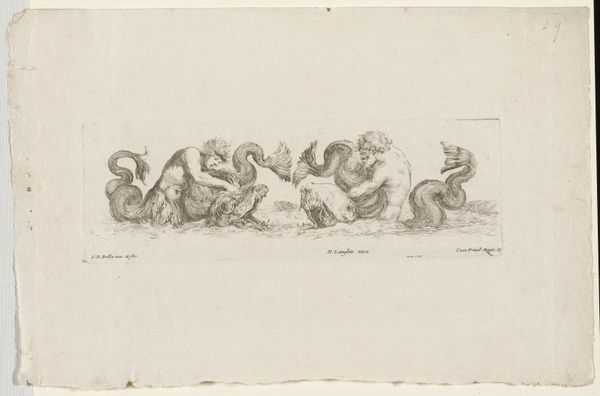

engraving

#

weapon

#

allegory

#

baroque

#

figuration

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 92 mm, width 260 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Samuel Bottschild created this engraving, "Putti met schild, helm en wapens," in 1693. It's currently housed here at the Rijksmuseum. What's your immediate impression? Editor: It's strangely…playful? The putti give a childlike innocence to otherwise serious objects of war. It definitely softens the implied aggression of the weapons. Curator: It's important to remember the engraving process. Bottschild had to meticulously carve those fine lines into a metal plate. Think about the skill, labor, and time invested to create those very intricate details on the shield and helmet. Editor: Absolutely, and in this period, depictions of cherubs often symbolized divine intervention or protection in battles and statecraft. It brings into question, for whom is this protection granted, and at whose expense? It invites reflection on the social implications of warfare at that time. Curator: Baroque art often intertwined these symbolic elements, right? It’s the means by which social hierarchies and powers would cement their position using iconography. It served a certain clientele who then also dictated how these tools were produced, no? Editor: Indeed, the image prompts considering power structures; these allegorical putti hint at dominant forces shaping historical and social narratives and making one wonder whether war itself gets ‘sanitized’ and abstracted. Is this perhaps not an accidental byproduct? Curator: Do you think this level of craftsmanship elevate weaponry from functional items into objects of cultural prestige? Editor: I see it as both, the putti evoke innocence yet there’s an unquestioned acceptance of the ‘grand theater of war’. Perhaps a wider reading might even explore it as critique in allegorical garb. Curator: The materials used – the metal for the plate, the ink for printing – were all resources, commodities. By distributing his engravings, the artist engages with networks of consumption and expands the dialogue. It underscores a crucial question: were these engravings affordable and distributed broadly or created for a highly selective group only? Editor: And in asking that you’ve highlighted it goes well beyond visual enjoyment. Looking at the engraving this way helps us view artworks like this beyond pretty imagery, opening discussions of how history, labor and artistic process come together, prompting challenging insights into past narratives. Curator: Indeed, viewing it as both propaganda and art encourages us to challenge conventional stories linked to these visual legacies.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.