print, engraving

# print

#

figuration

#

11_renaissance

#

line

#

cityscape

#

history-painting

#

northern-renaissance

#

engraving

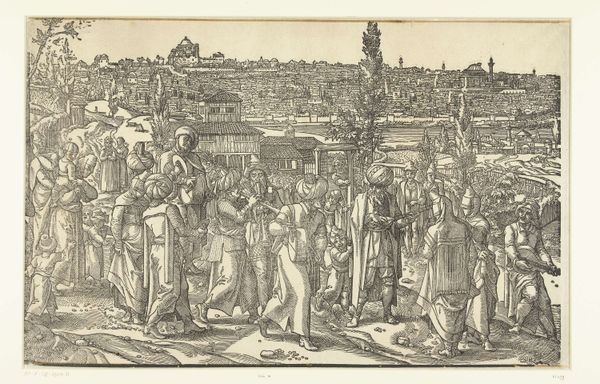

Dimensions: height 299 mm, width 394 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

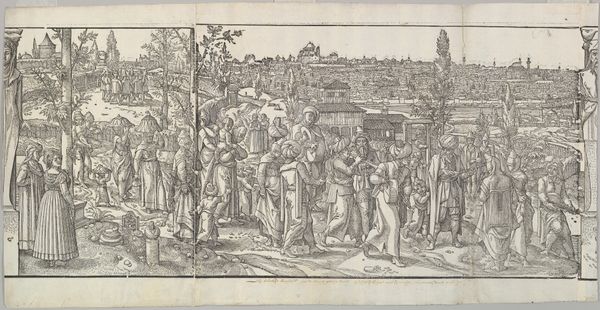

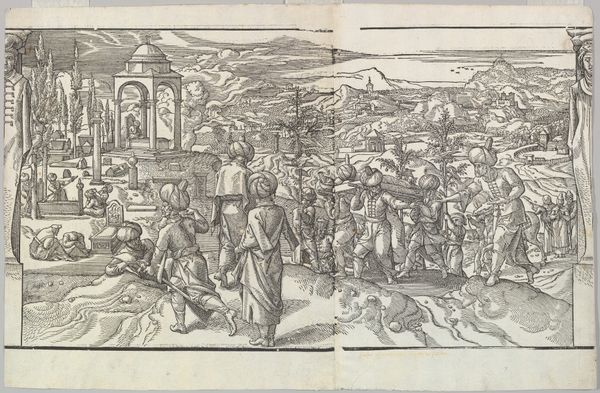

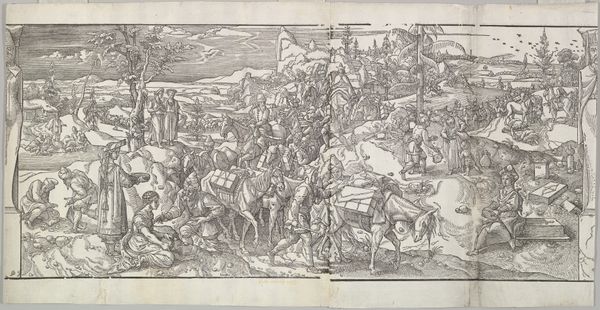

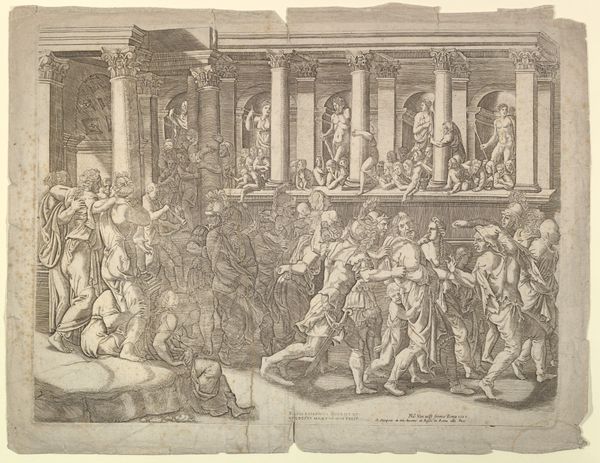

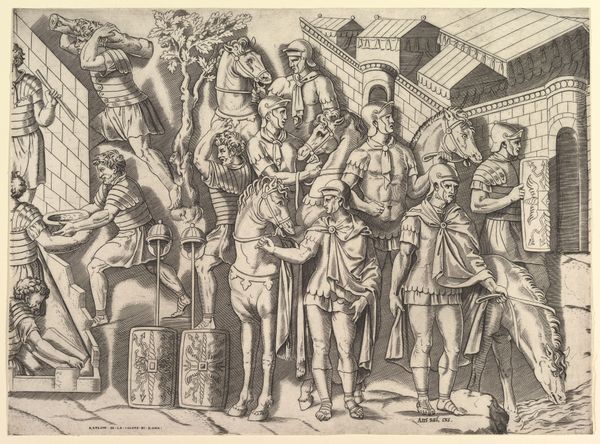

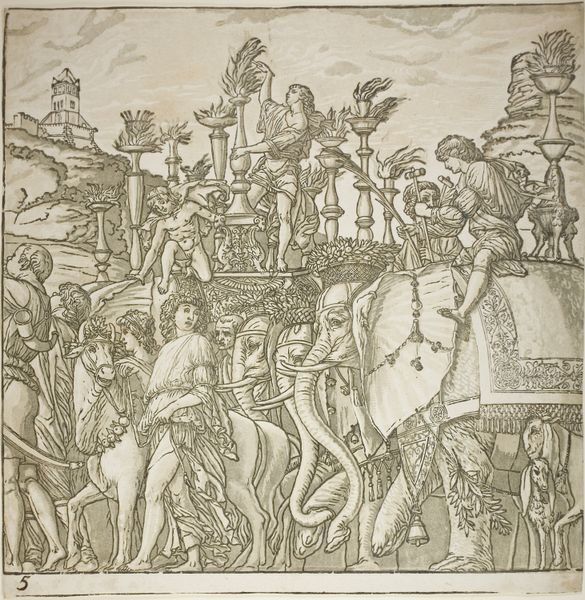

Curator: Here we have the "Procession of Suleiman I," dating back to 1553, made by Pieter Coecke van Aelst, currently residing here at the Rijksmuseum. It's an engraving, capturing a scene of grand pageantry. Editor: Immediately, I'm struck by the intense detail and almost relentless energy, wouldn't you say? Like a snapshot from a dream about historical encounters and exotic places, charged with a restless kind of graphic energy. Curator: Absolutely. Van Aelst’s depiction isn’t just ornamental. As a printmaker, he disseminated images of Ottoman power and culture throughout Europe, and this work provides crucial insight into Renaissance perceptions—and projections—regarding the Ottoman Empire, specifically under Suleiman the Magnificent. It also tells us something about print culture in that period and how information was disseminated visually and culturally. Editor: Projections—that’s a sharp way to put it. I sense this work isn’t necessarily a neutral observation. Look how the artist captures this event. Everything seems intentionally designed to impress. Almost theatrical, in the slightly artificial layout and character types, so what does this staged effect achieve for Van Aelst and his patrons? Curator: Good question. While based on his actual travels, the work plays into established visual tropes of depicting power, echoing Renaissance artistic principles. In presenting such visual dramas in prints, it amplified imperial ideas but for whom and for what purpose? It also reflects an ambivalent early modern perspective on the Ottomans. They are depicted as simultaneously formidable and strangely appealing, offering a kind of dangerous exoticism for a European audience. Editor: Yes, appealing. I’m strangely captivated by the texture that you see from just looking and this kind of obsessive linework—a city teeming, the detailed robes—as if Van Aelst is trying to materialize an entire civilization through these marks. Do you see anything in particular when it comes to line, repetition and symbol here? Curator: Van Aelst employs intricate lines and varied textures not just to achieve visual detail but also to symbolize power and status. Note, for instance, how Suleiman himself is centrally located atop horseback to convey the authority embedded in leadership. Also think about the procession itself: an intentionally long and carefully depicted entourage meant to create and impress and shape beliefs of their subject throughout the 16th Century. Editor: Such careful composition does convey a deep purpose. Imagining a historical procession become this detailed print almost connects with me the artistic imagination in historical storytelling. Thanks for helping make that come alive, a real voyage across cultures. Curator: And thank you for providing an alternative and different lens, which provides greater insight into its historical narratives.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.