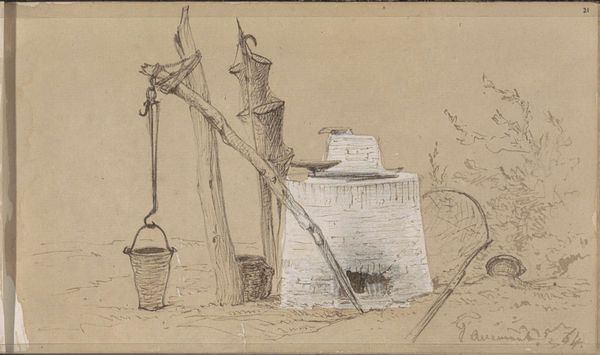

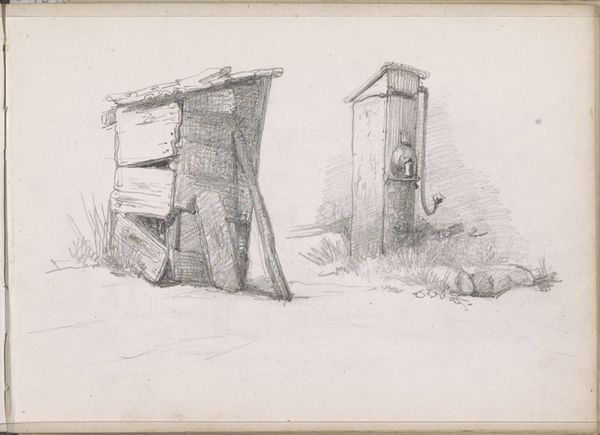

print, etching

#

16_19th-century

# print

#

etching

#

landscape

#

realism

Dimensions: height 90 mm, width 128 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

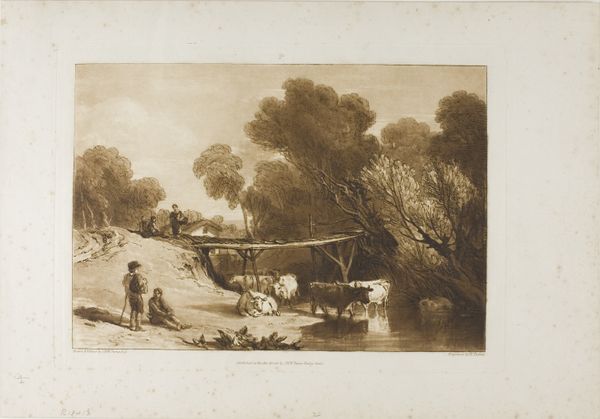

Editor: Here we have Cornelis Steffelaar's etching, "Waterput met hefboom," created sometime between 1807 and 1861. It depicts a well with a lever in a rural landscape. The stark black and white tones create a rather somber, almost nostalgic, feeling. How do you interpret this work? Curator: It's interesting that you mention nostalgia. For me, this image serves as a stark reminder of the labor often erased in romanticized depictions of rural life. Look at the detail in the well, the wear and tear on the wood. Consider the historical context; this was a time of immense social change and upheaval in Europe. The Industrial Revolution was pushing people into cities, and this print aestheticizes a lifestyle that was rapidly disappearing but, crucially, one built on strenuous labor and unequal access to resources like water. Editor: I hadn't considered the labor aspect so directly. I was more caught up in the aesthetic of the etching itself. So, you're saying it's less about an idealized countryside and more about pointing to the realities that underlie such idyllic scenes? Curator: Precisely. Think about who this print was made for. Most likely, it was intended for an urban audience, perhaps those who had benefitted from industrialization but felt a certain detachment from the land and rural labor. This image, while seemingly pastoral, acts as a subtle commentary on class divisions and the cost of progress. Steffelaar’s choice to highlight a water well, a vital and often contested resource, isn’t accidental. Editor: So, by focusing on something as fundamental as a water well, Steffelaar is making a statement about access and maybe even sustainability before those concepts were widely discussed? Curator: Absolutely. He's prompting us to question who has access to clean water and at what cost, connecting rural life to the wider sociopolitical landscape of the 19th century. Editor: That’s a powerful reading. I'll definitely look at these landscapes with fresh eyes now, considering not just the scenery, but the silent stories they hold about labor, access, and social change. Curator: Indeed. Art has a way of speaking volumes, especially when we listen critically to its historical and social echoes.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.