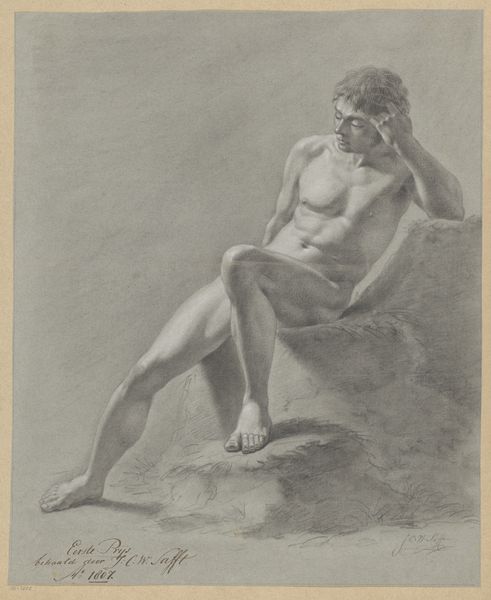

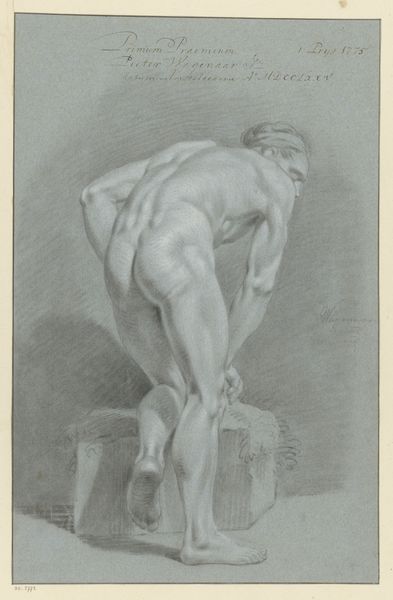

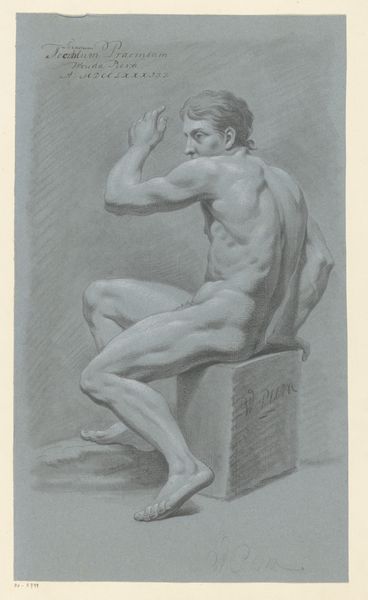

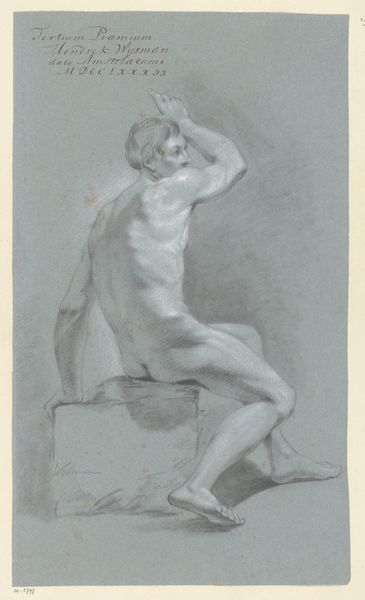

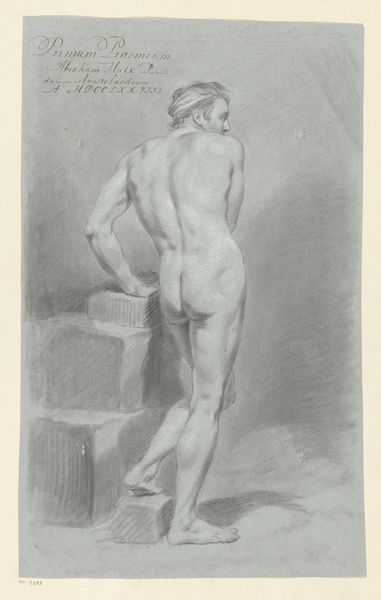

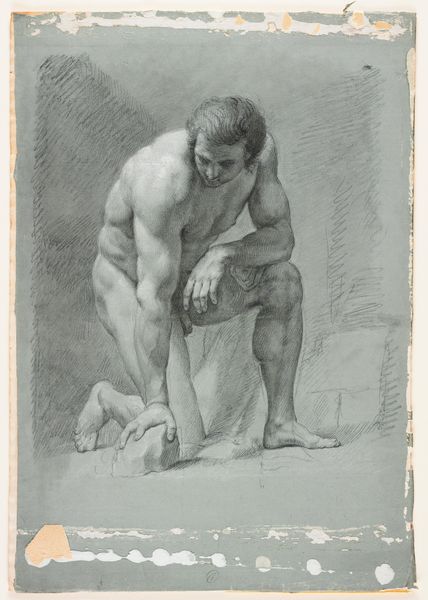

Knielend mannelijk naakt, van opzij gezien (1e prijs 1809) Possibly 1809

0:00

0:00

drawing, pencil

#

portrait

#

pencil drawn

#

drawing

#

pencil drawing

#

pencil

#

portrait drawing

#

academic-art

#

nude

#

realism

Dimensions: height 457 mm, width 333 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

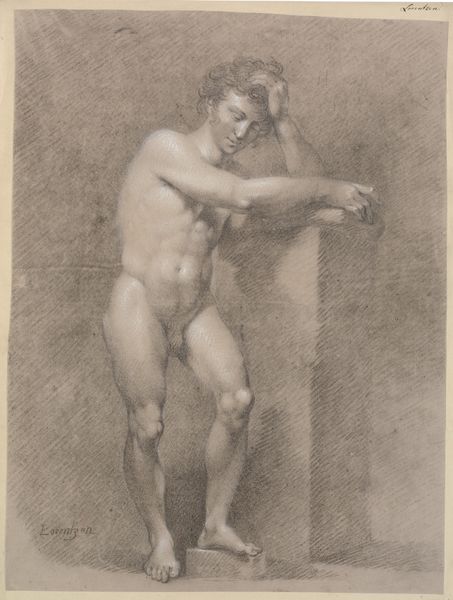

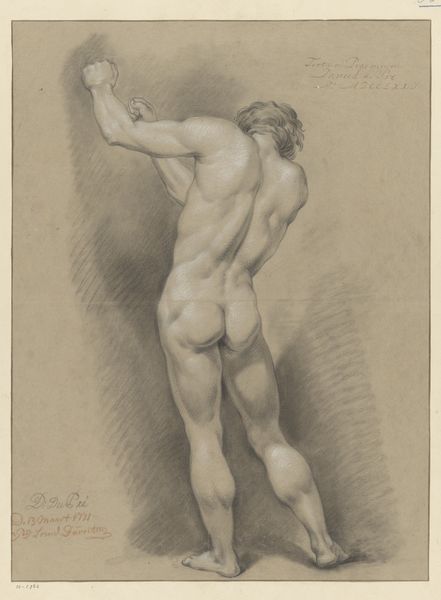

Curator: This is "Kneeling Male Nude, Seen from the Side (1st prize 1809)" attributed to Henricus Franciscus Wiertz, likely created around 1809. It's a pencil drawing on paper. Editor: It strikes me as rather somber. The figure's bowed head and clasped hands—bound, it appears—project a feeling of submission or perhaps defeat. The muted grayscale palette reinforces that mood. Curator: Yes, the use of a kneeling nude was common for academic art, meant as a study for history paintings or other large-scale works that demonstrated a mastery of the human form and its classical ideals, this piece was actually awarded first prize in 1809! The nude in art at this time also reflects the complicated intersection of art education, public morality, and neo-classical ideals following the French revolution. Editor: Note how Wiertz employs chiaroscuro to sculpt the figure's musculature, imbuing it with volume and a palpable sense of weight. The strong contrasts illuminate the back and shoulder, while the head and extremities remain partially obscured, focusing our attention on the subject’s emotional center. It’s a very effective deployment of line and shading to convey both physical form and psychological state. Curator: Absolutely. This type of study drawing became critical to larger societal discussions about art's public function, its relation to the burgeoning nationalism present in Europe during the early 19th century. How could it continue to operate in a post-revolutionary world? Wiertz shows us how such drawings walked the line between artistic merit, social symbolism and public accountability. Editor: It certainly showcases a control of form; a mastery of representing the human body through tonal variation. To think, a single pencil could produce this full, rounded image of life itself. Curator: Considering the Academy context and time in history, the nude subject could have served also as the object of idealized social hopes. Perhaps art would represent freedom, or become associated with national values of strength, virtue, and beauty during a tumultuous moment in Europe's own becoming. Editor: An intriguing perspective that gives the piece further depth and context. I now see this figure less as solely an object of artistic study, and more as a symbol caught between ideals of revolution and nation. Curator: Exactly, art serves as an ongoing barometer of culture's temperature, recording subtle pressures over decades and movements.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.