Portret van een hertog, mogelijk Heinrich von Saksen-Merseburg 1670 - 1713

0:00

0:00

pieterschenk

Rijksmuseum

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

# print

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 247 mm, width 180 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

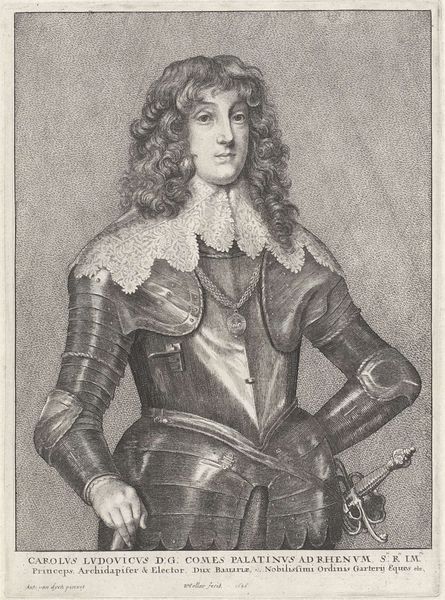

Curator: Pieter Schenk’s "Portret van een hertog, mogelijk Heinrich von Saksen-Merseburg," likely created between 1670 and 1713, stands before us. What strikes you immediately? Editor: Oh, the *weight* of it all! The literal weight of that armor, the potential weight of command... and maybe just a tiny bit the weight of the subject himself. It feels... burdened, somehow, despite the grand setting. Curator: The weight of representation is always fascinating, especially in Baroque portraiture. Armor, in theory, symbolizes strength and protection, yet it also could feel performative, creating a particular masculine ideal tied to war and social order. Heinrich's assured stance amidst what appears to be a battlefield implies power, doesn't it? Editor: Implies it, perhaps. But also exposes it as something consciously *constructed*. It seems so posed! Almost like he is swallowed by all that metal; the frothy wig fights for dominance and somehow seems to humanize him against this unyielding metal exterior. Curator: It's fascinating how this engraving captures texture—the cold, polished steel contrasted with the organic, almost untamed hair. It also brings to mind how the power of portraiture at that time played into political power structures, like the duchies within the Holy Roman Empire that Heinrich would have navigated. What message would such a print send about his authority and lineage? Editor: I suspect it depends on who the intended viewer was. It plays into the iconography of lineage and power. However, I'm also wondering about the casualties, often hidden, unseen. If you glance at the background battle scene, do you observe any narrative suggesting concern with the individual fighters facing all that heavy metal or, at least, their suffering? Curator: Schenk offers an idealized representation—a duke, framed by battle, yet untouched by its true cost. The print becomes a study in curated masculinity of the era; he's staged and stately. He isn’t in the thick of it; the background merely *alludes* to combat, to courage and heroism. But there is no real vulnerability. Editor: Which serves to underline the purpose of images in the 17th and early 18th centuries. Propaganda dressed up as remembrance. These images were less concerned with historical accuracy, representing truth than projecting the idea of unquestionable strength and power. Curator: I find that especially fascinating in an engraving. The print medium makes it reproducible, and this portrait becomes more pervasive and potentially shaping opinions across the realm. It’s a powerful intersection of art and power. Editor: Precisely! A dialogue between crafted persona and cold, hard… engraving.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.