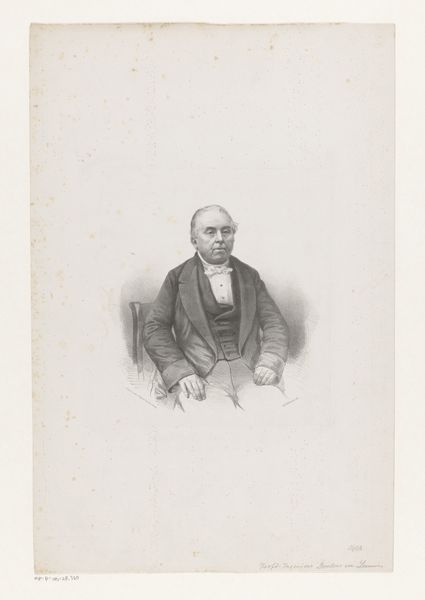

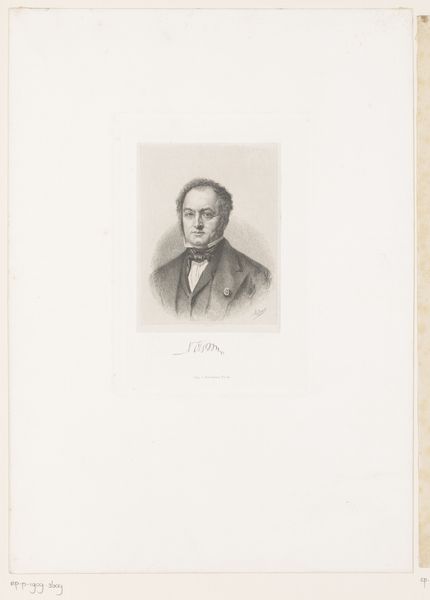

drawing, pencil

#

portrait

#

pencil drawn

#

drawing

#

pencil sketch

#

charcoal drawing

#

pencil drawing

#

pencil

#

portrait drawing

#

academic-art

#

realism

Dimensions: height 513 mm, width 430 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

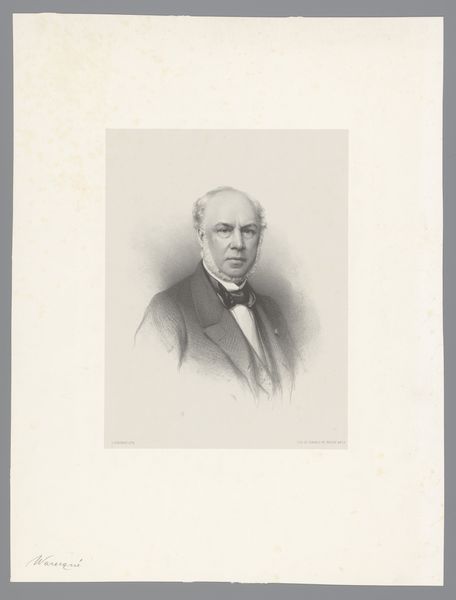

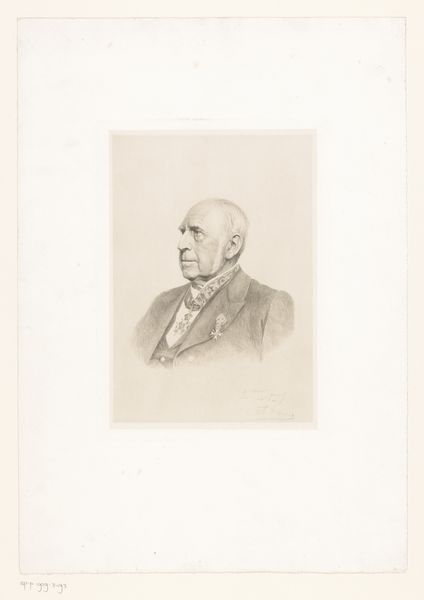

Curator: Up next we have Adrianus Johannes Ehnle's 1854 pencil drawing, “Portret van Christiaan Bernhard Tilanus.” Editor: Oh, the severity of that gaze! He looks like a headmaster who’s just caught you cheating on a Latin exam. But the execution! What patience to build up those tones with pencil. Curator: Indeed! Ehnle clearly understood the weight of portraiture in solidifying bourgeois identity at that time. It’s a study in understated power, carefully constructed and deeply entrenched in social expectations. Editor: But is it, though? Maybe it's simply capturing the mood of Tilanus, who maybe *was* feeling like a headmaster that day! The artist isn't necessarily endorsing power; they could just be mirroring it. I like how the delicate hatching almost vanishes into the blank paper. There's a fragility there, too, beneath the apparent stoicism. Curator: I take your point. The technique itself becomes part of the narrative. It mirrors the tension inherent in these kinds of commissioned pieces. Artists relied on them, yet these works reinforced very specific codes. It becomes part of a feedback loop. Tilanus likely understood this dance, commissioning Ehnle knowing precisely the statement the portrait would convey. Editor: Hmm, I'm still seeing something vulnerable in the wisps of graphite that almost disappear around his shoulders, as if the artist himself were unsure if this figure should really be THERE, permanently fixed to the paper. Does the Realism tag fully hold here? Curator: That tension you identify is a perfect example of what made realism such a compelling, yet tricky aesthetic! There’s the desire to represent the individual, as they are, and this struggle against prescribed social roles of how one *should* appear. Editor: The debate goes on and on… Ultimately, it speaks volumes about both sitter and artist. Perhaps the value isn't in a final, conclusive reading, but in how it continuously prompts discussion and questions of the era.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.