photography, albumen-print

#

landscape

#

photography

#

genre-painting

#

albumen-print

#

realism

Dimensions: height 156 mm, width 220 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

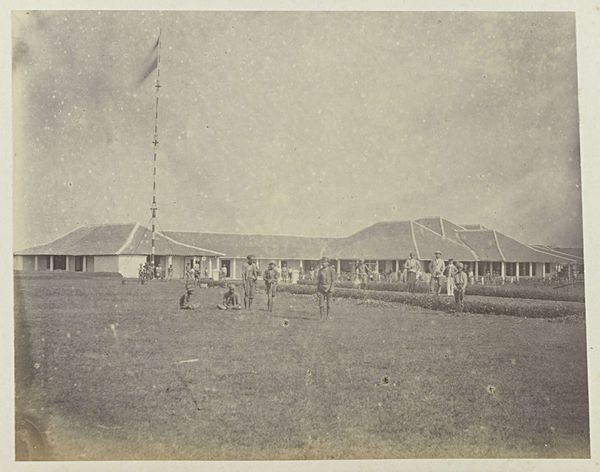

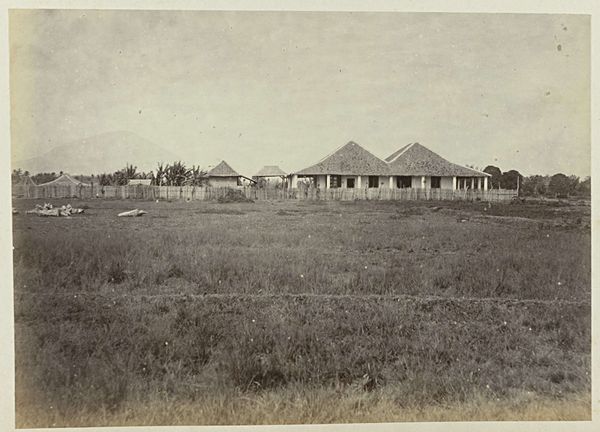

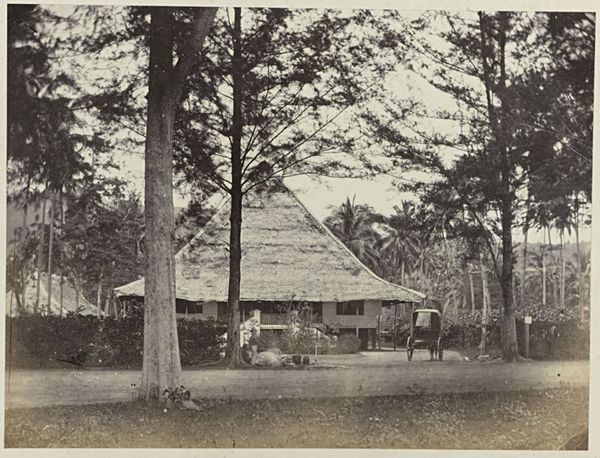

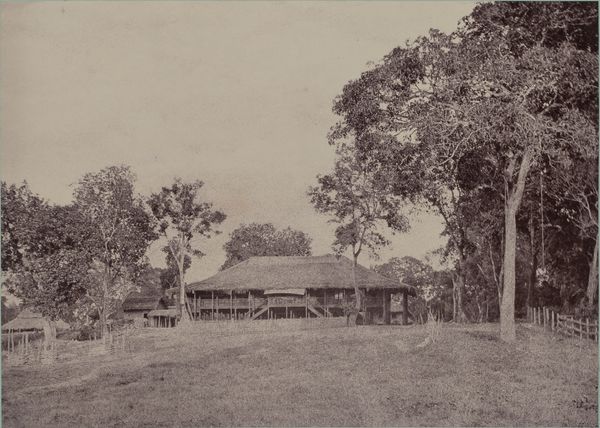

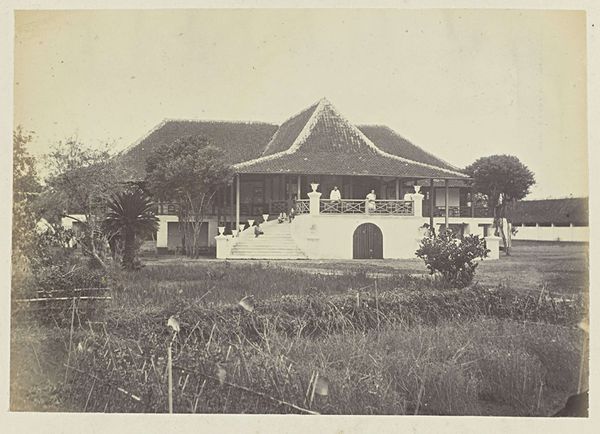

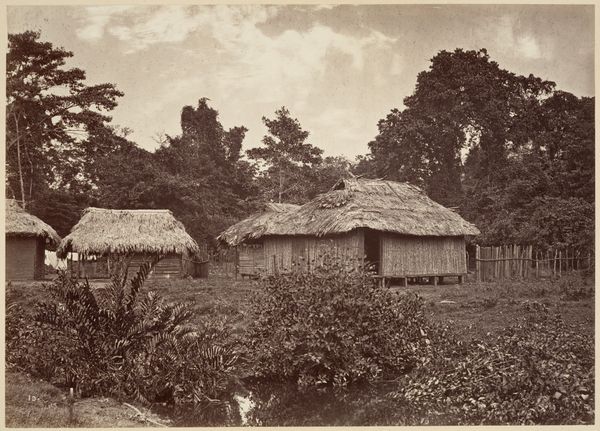

Curator: This is an albumen print called "Werknemers op een onderneming," which translates to "Employees at an Enterprise," attributed to Woodbury & Page and dating from somewhere between 1863 and 1869. It’s part of the Rijksmuseum’s collection. Editor: What strikes me immediately is this almost performative staging of labour. It's as though the workers are being presented, more than simply represented. It's strangely…idyllic and unsettling all at once. Curator: That's astute. On one level, it's a genre scene, trying to capture everyday life. But beneath that, consider the colonial context. Woodbury & Page were active in the Dutch East Indies, present-day Indonesia. Editor: Precisely. So, we have to unpack whose gaze is shaping this “reality.” The albumen print, a photographic process that allowed for mass reproduction, becomes a tool. Who is commissioning these images? What stories are they intended to tell about labour, power, and empire? Curator: I find it interesting how the workers appear to be posed, not engaged in actual tasks, adding to the sense of this staged tableau you pointed out. Their positioning feels strategic—arranged like objects within the colonial landscape, mirroring the order that the colonists aimed to impose. It speaks of both control and romanticism in an uncomfortable harmony. Editor: And what about the space? A foreground seemingly filled with vegetation. A literal and figurative barrier or division perhaps, between the viewer – the coloniser – and the colonised. Consider too, how this constructed visual narrative affects our contemporary reading. The lack of names, stories, individuality—the photograph turns the subjects into types rather than individuals, almost tools. Curator: It's true. Looking closely, the sepia tones add to the feeling of distance, both temporal and emotional. The soft focus softens the edges of a brutal system. But acknowledging that removes some of its aesthetic power I think. It humanizes the victims by looking deeper into this depiction of colonialism. Editor: Absolutely. It is precisely this tension that I find so compelling. The aesthetic appeal that holds within it uncomfortable, painful truths, demanding a reading beyond a mere ‘pretty picture’. This picture is very charged in our current cultural climate. Curator: So in short, we see more than an attractive scene but an unsettling record of a system— one that benefitted from oppression. What lingers now, is perhaps how we deal with it. Editor: Indeed. It makes us critically aware about how historical images continue to shape the present, demanding from us critical understanding and perhaps more importantly, empathy.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.