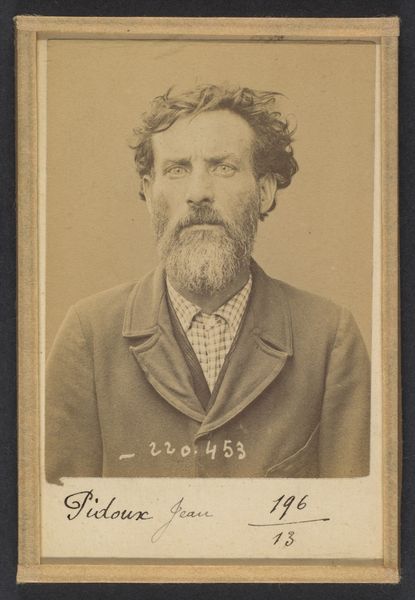

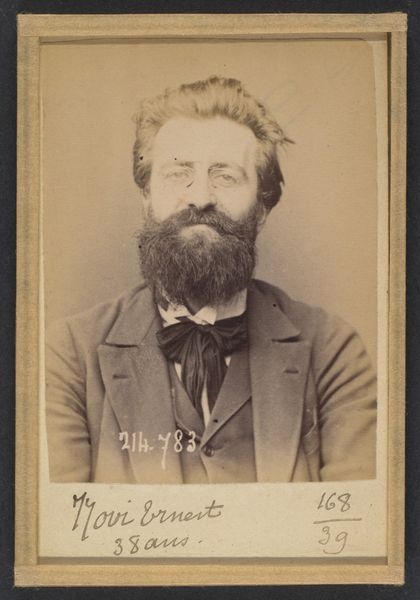

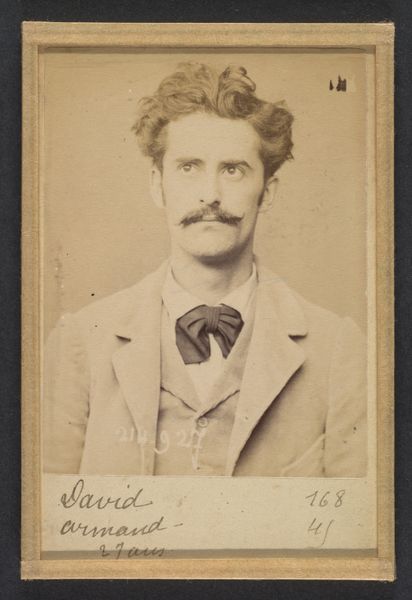

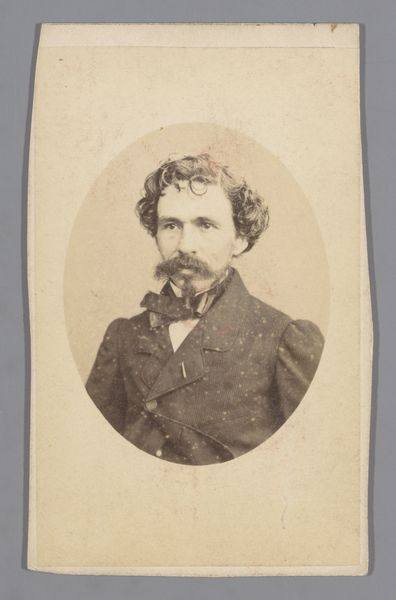

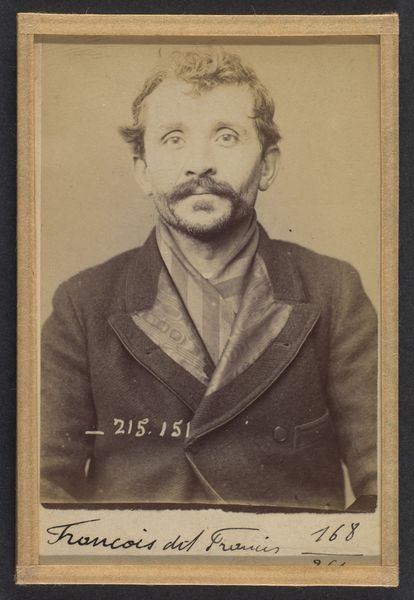

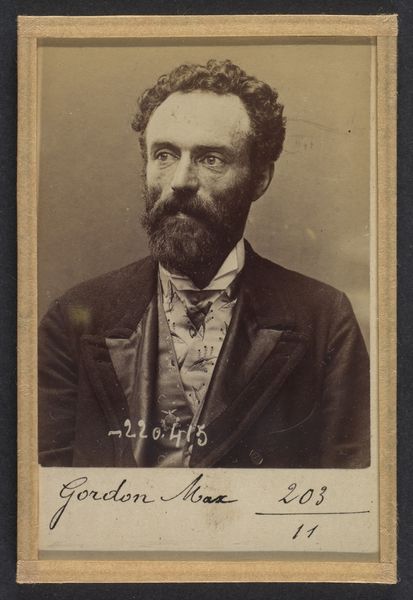

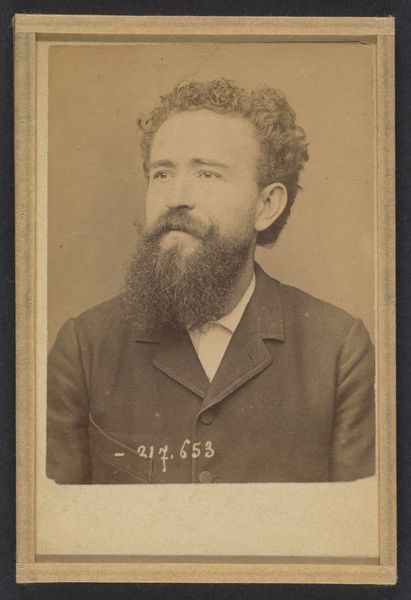

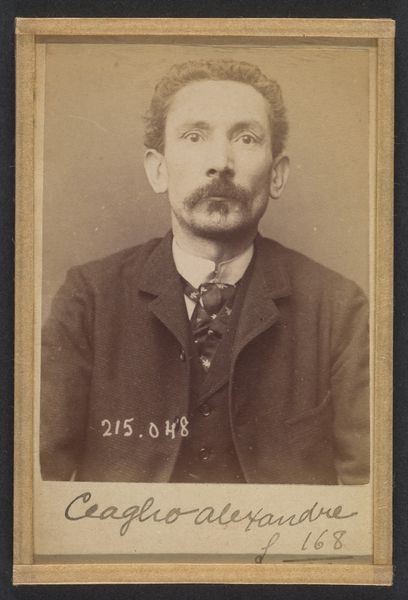

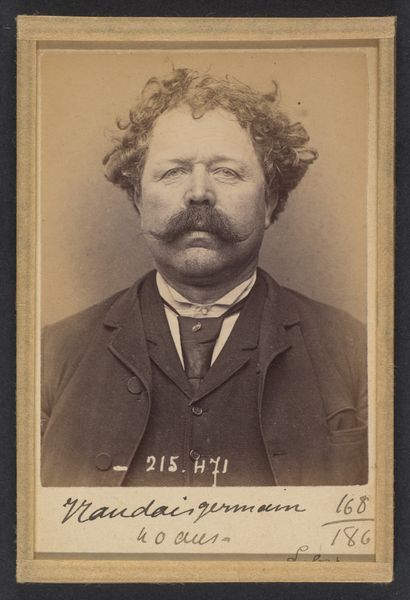

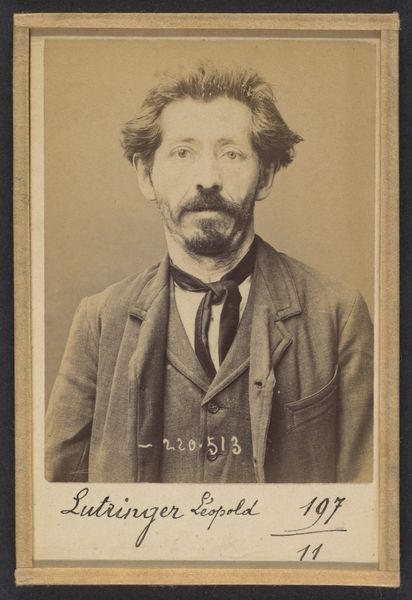

Biais. Fernand, Alphonse. 41 ans, né le 28/6/53 à Laval (Mayenne). Tourneur sur bois. Anarchiste. 2/7/94. 1894

0:00

0:00

photogram, photography

#

portrait

#

photogram

#

portrait

#

photography

#

realism

Dimensions: 10.5 x 7 x 0.5 cm (4 1/8 x 2 3/4 x 3/16 in.) each

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: This photograph, taken in 1894 by Alphonse Bertillon, presents a compelling portrait titled "Biais. Fernand, Alphonse. 41 ans, né le 28/6/53 à Laval (Mayenne). Tourneur sur bois. Anarchiste. 2/7/94." Editor: The first thing that strikes me is the man's gaze; direct, perhaps defiant? There is an intriguing mix of weariness and determination etched into his features. Curator: Indeed. Bertillon pioneered judicial photography and anthropological criminology, a deeply problematic aspect of late 19th-century positivist criminology and police procedure. It reduced people to statistics in a context that was often, and tragically, racist and xenophobic. This portrait, a 'mugshot' by another name, is part of that project. Editor: Right, knowing this context changes everything. The slightly unkempt appearance coupled with the intense look gains even more significance. His full beard and hair suggest a disregard for societal norms. Does "tourneur sur bois" add another layer? Curator: Absolutely. A wood turner is a craftsperson. By noting his profession and anarchistic beliefs, Bertillon offers, or seems to offer, more information. This was intended to help classify, track, and ultimately control individuals perceived as threats to the social order. But, as with so much of the information that such bureaucratic practices seek to impose, we have to read with deep suspicion here. Editor: And what symbols can we attribute? Does his slightly loosened shirt represent anything specific? Perhaps something about freedom of expression? The portrait seems both candid and constructed. Curator: That might be reading a bit too much into it! More broadly, Bertillon’s practice relied on visual shorthand; signifiers like clothing, facial hair, and, of course, written descriptions were tools to classify and essentialize the individual to a set of stereotypes, regardless of facts or social context. We should read those signs suspiciously, as a flattening, not as symbolic freedom. Editor: Point taken. It's easy to let our fascination with visual cues run wild, especially with historical pieces. Perhaps the real story lies in acknowledging our subjective reading, shaped by time. It also humanizes Biais—returning him, partially at least, from the grips of documentation. Curator: Exactly. Instead of being trapped within Bertillon's framework, we might understand something more vital by exploring the sociopolitical context behind these portraits, seeing the individuals as active agents within a period of considerable political repression and prejudice. Editor: Looking back, I am left to admire, in a way, the resilience of his humanity as conveyed across time and within such dehumanizing apparatus. Curator: A vital counter-perspective, I think, and essential to acknowledging the power, limitations, and enduring afterlives of the photographic portrait.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.