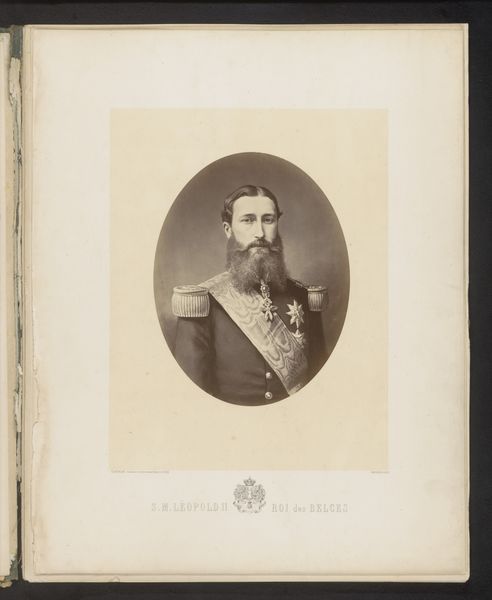

Fotoreproductie van een geschilderd portret van Abdülhamid II, sultan van het Ottomaanse Rijk before 1880

0:00

0:00

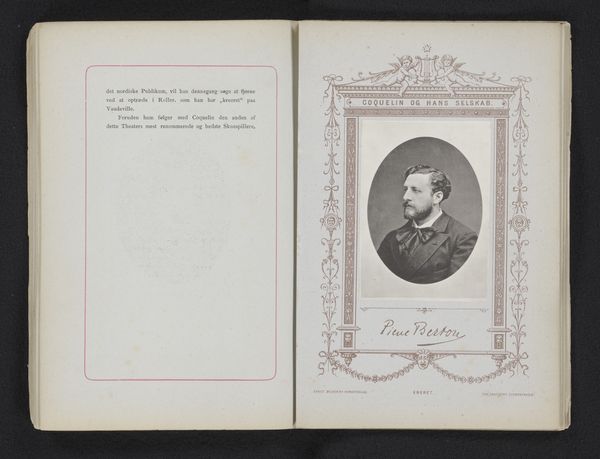

photography

#

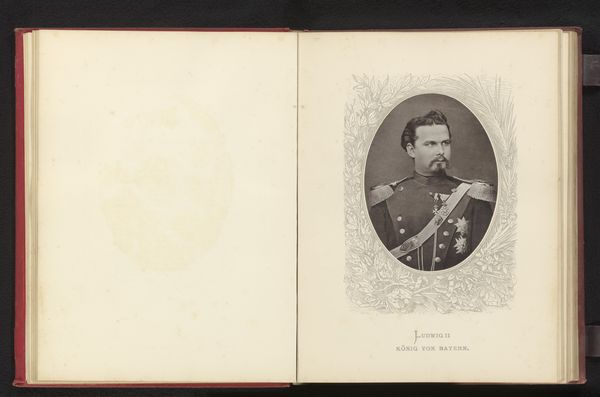

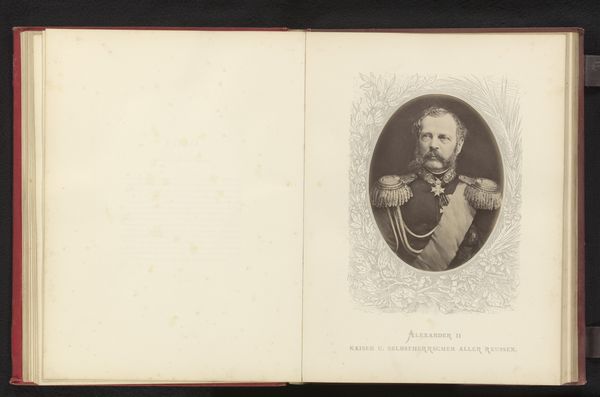

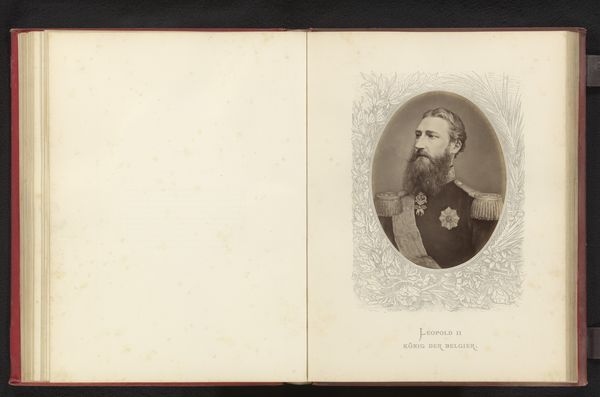

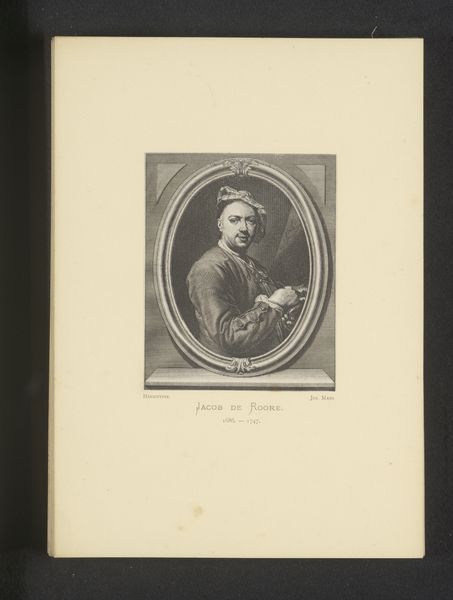

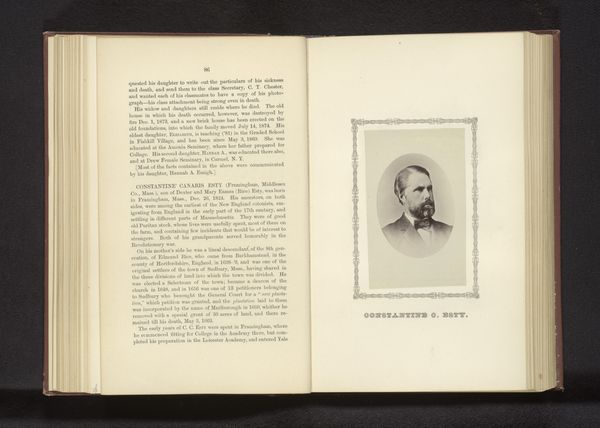

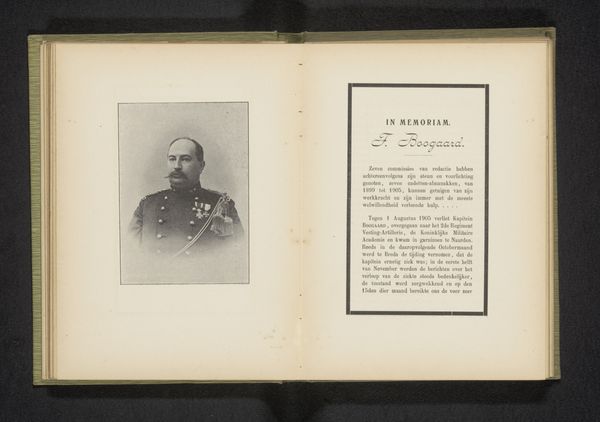

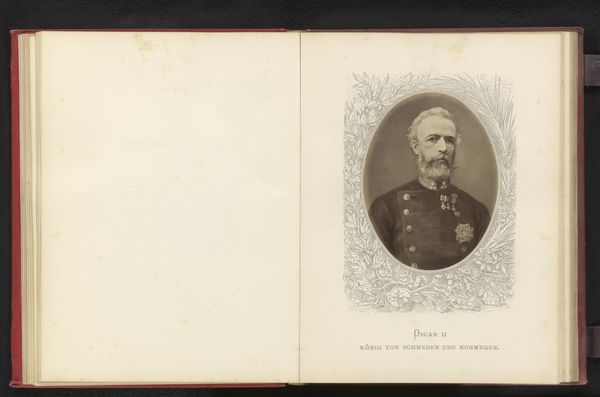

portrait

#

aged paper

#

toned paper

#

homemade paper

#

sketch book

#

hand drawn type

#

photography

#

personal sketchbook

#

hand-drawn typeface

#

orientalism

#

thick font

#

sketchbook drawing

#

islamic-art

#

sketchbook art

Dimensions: height 189 mm, width 142 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

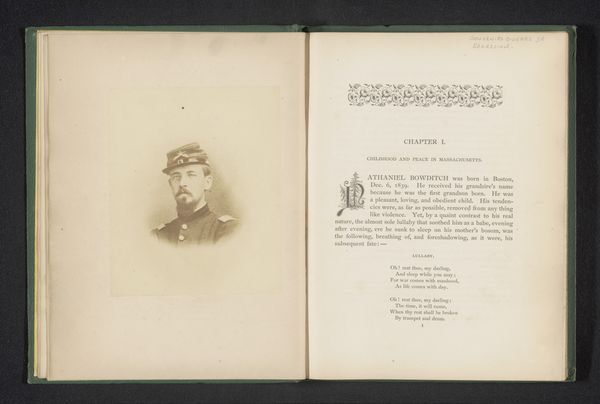

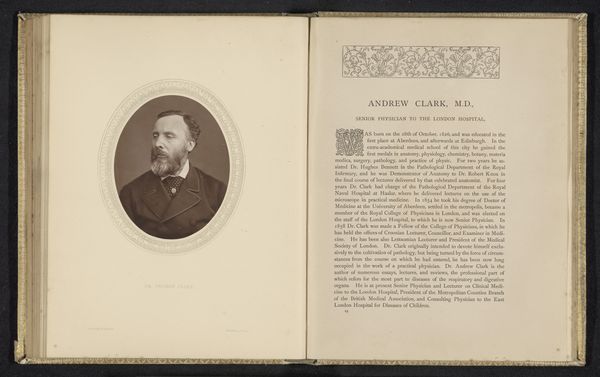

Curator: Before us, we have a photogravure reproduction of a painted portrait, depicting Abdülhamid II, the Sultan of the Ottoman Empire. This image likely dates before 1880, judging from the stylistic elements and photographic techniques employed. Editor: My immediate reaction is of stark formality, almost oppressive. The symmetrical composition, framed within what appears to be a page from a sketchbook, conveys an intense sense of power, even with its subdued sepia tones. Curator: Precisely. The formal pose, set against the ornamental oval and the meticulously crafted inscription, presents him as a figure of established authority. It follows typical orientalist visual codes, albeit reproduced as a photograph rather than an oil painting. Note how the details of his attire, from the fez to the elaborate embroidery, emphasize regal bearing. Editor: Yes, and thinking about the materiality of the photograph, it really shifts our perception. It transforms a royal image into a mass-producible commodity. This speaks volumes about shifting power structures and the dissemination of images during the late 19th century. Who created the painting, how was the image then converted into a photograph and widely distributed – questions we must consider. Curator: Indeed. The reproductive nature removes some aura of originality but allows the image to take on new significance within a modern, industrial context. Its dissemination impacts meaning, echoing, for instance, Benjamin's ideas on art in the age of mechanical reproduction. It also subtly collapses distinctions between handmade and machine-made art objects. Editor: Ultimately, this image serves as a historical artifact demonstrating a moment where photographic techniques begin shaping and spreading ideals of imperial power, not only impacting but restructuring art's production, labor, and exchange values. It forces us to confront power's ever-evolving face in changing eras of making. Curator: Very astute. It brings us back to the materiality of images. Editor: Well said.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.