print, engraving

#

portrait

#

pen drawing

# print

#

figuration

#

11_renaissance

#

line

#

northern-renaissance

#

decorative-art

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 24 mm, width 72 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

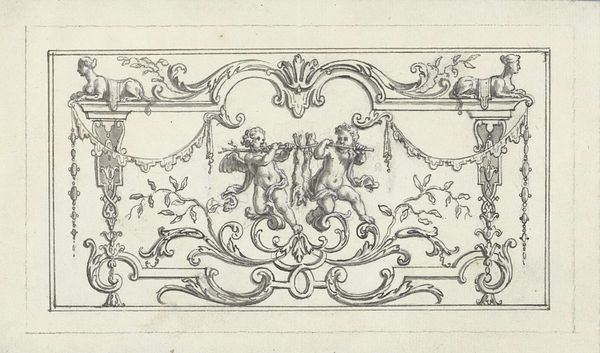

Curator: It's intriguing, isn't it? This print, titled "Frieze with Two Children and a Cherub," was created in 1532 by Heinrich Aldegrever and is held here at the Rijksmuseum. The technique, an engraving, gives it a very linear quality. What's your initial take on it? Editor: I'm immediately drawn to the symmetry and those fleshy cherubs. It has a strange sense of decorative violence to it, somehow... the cherubs feel trapped, pinned within this rigid frieze. Curator: A fitting observation! Aldegrever was a master printmaker. Consider the process—the precise tooling required to etch these fine lines into a metal plate. This wasn't "high art" in the traditional sense, but a designed object intended for broader circulation, a means of disseminating style and influencing craft production. Editor: Absolutely. Looking at the cherubs in the context of 16th-century anxieties about childhood mortality and the idealized cherubic form promoted by the Church, I wonder about its intent. Is it simply decorative, or does it carry some more profound meditation on innocence and loss, perhaps even power dynamics? Curator: The production context offers a perspective, particularly thinking about the engraver's labor and skill. Aldegrever was positioning himself within a network of artisans and consumers. These prints had value as models for other artists, or to show status when owned and displayed. Editor: True, but what statements are made here with the human subjects in such artificial positions? The work becomes quite compelling when reading the iconographic meaning of these cherubs as it contrasts against a geometric pattern in a post-Reformation Europe rife with religious upheaval. There's a push and pull, a negotiation, that transcends pure decoration. Curator: So, are we looking at art object as agitprop? Or as an exercise in craft? The conversation itself exemplifies Aldegrever’s role as a catalyst within that network, mediating production and consumption, and opening up further cultural possibilities. Editor: Maybe, but the potential here for subversive undertones is something to reckon with—as well as the social and political ramifications, don't you think? Regardless, the tension is thought-provoking. Curator: Indeed. Its complexity reminds me that material history allows us not just to contextualize objects, but to really open our thinking towards the time of production. Editor: Yes, now I want to go read some cultural theory.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.