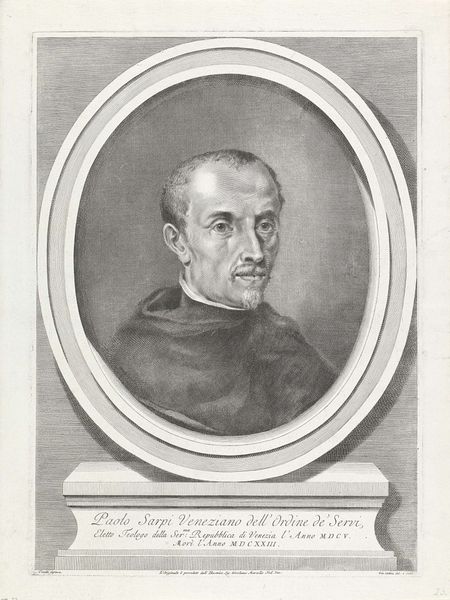

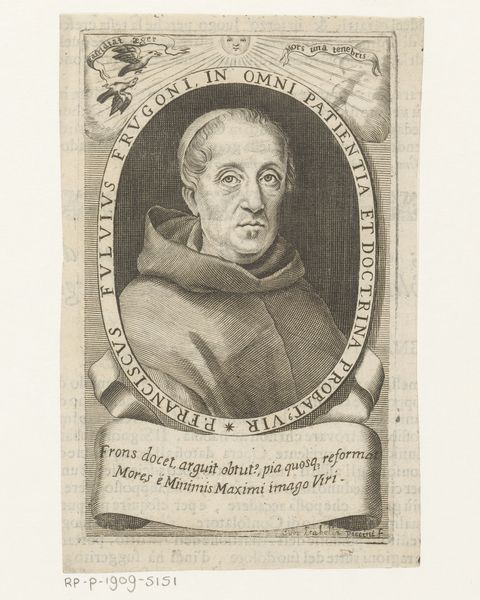

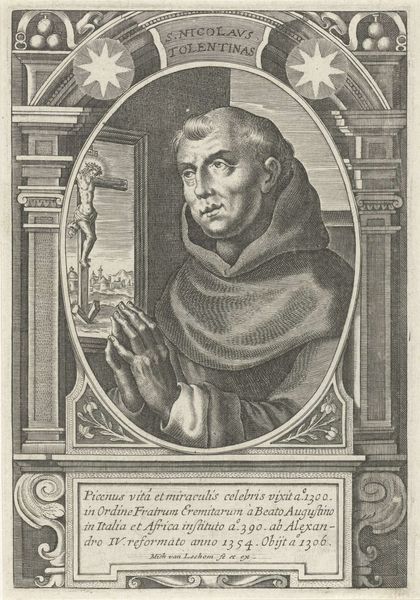

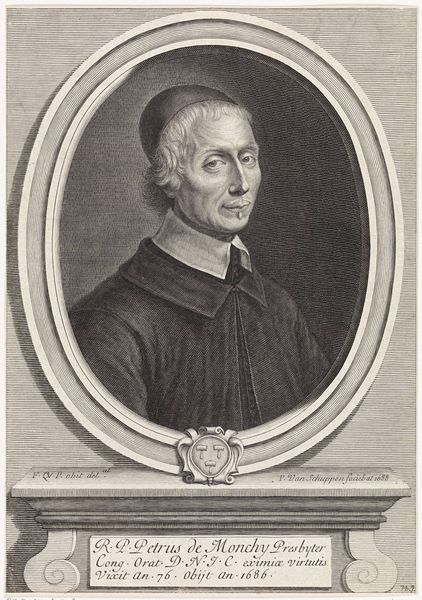

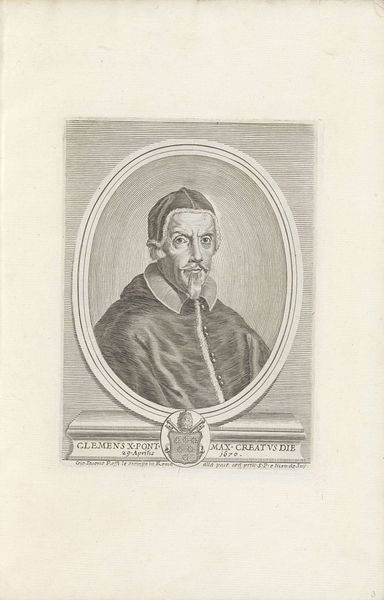

engraving

#

baroque

#

old engraving style

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 287 mm, width 181 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

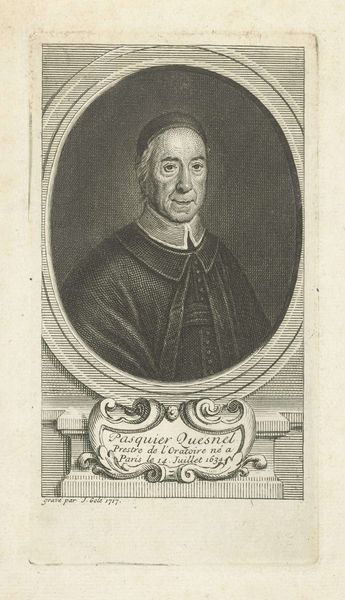

Editor: So, we have before us a rather intriguing engraving from 1722, titled "Portrait of Bertrand Monsinat, a Cleric from Toulouse," by Arnold van Westerhout. It has a somber feel, doesn't it? The figure's dark robes really contrast with the crisp lines of the engraving. What jumps out at you? Curator: Indeed. These portrait engravings served a very particular socio-political purpose. They weren't simply aesthetic objects but functioned as tools for constructing and disseminating power and authority within the Church and beyond. Consider how this image circulates: what statement is it making about Monsinat’s status? Editor: Well, it certainly seems to be promoting his importance. He's framed very deliberately, with that inscription and emblem. So, how did images like this function within the context of 18th-century religious and social structures? Curator: Exactly! These prints acted as a form of visual propaganda, solidifying Monsinat’s image as a reverent and learned figure within the Church hierarchy. Notice how the print mimics the style of an oil painting. Who has traditionally been represented in this manner, and why would the Church want to imitate such portraits? Editor: I guess to legitimize him further, by associating him with other people of status and power who have been previously represented this way? By showing him in the artistic conventions of nobility? Curator: Precisely. The engraving, as a reproducible medium, ensured wider dissemination and amplified the Church's message, playing a vital role in shaping public perception. Think about how these portraits contributed to a cult of personality around religious leaders. Editor: That’s fascinating. I hadn't really considered how much these engravings actively participated in building a public image and asserting institutional power. Curator: The politics of imagery, isn’t it thought provoking? We need to be aware that such a realistic portrait might involve strategic enhancements and manipulation of Monsinat's face, or in fact the construction of his ideal look. It all contributed to the symbolic representation and celebration of leadership and authority during the Baroque period. Editor: This definitely gives me a new appreciation for engravings, beyond just their aesthetic value. Curator: Likewise. I'm reminded of how art always operates within these networks of power. It prompts me to think more about which images circulate and for what reasons.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.