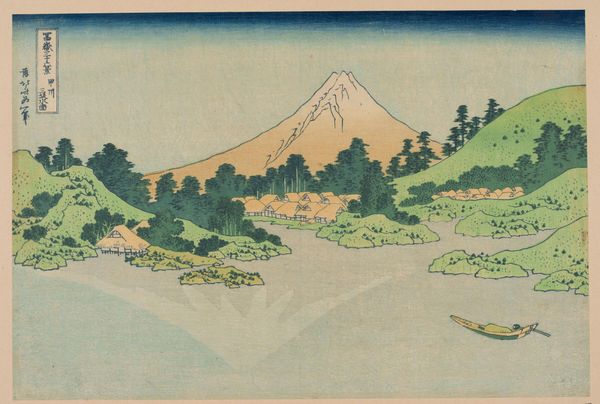

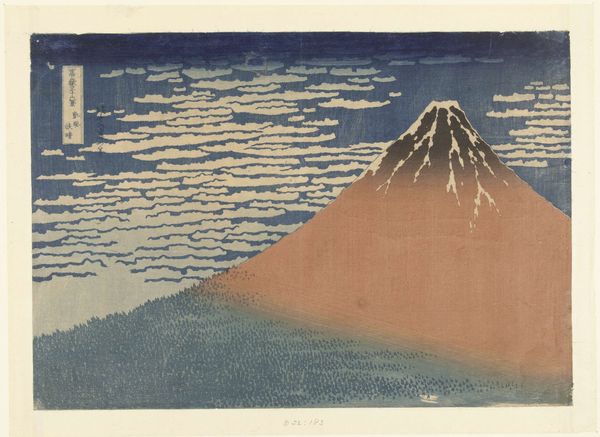

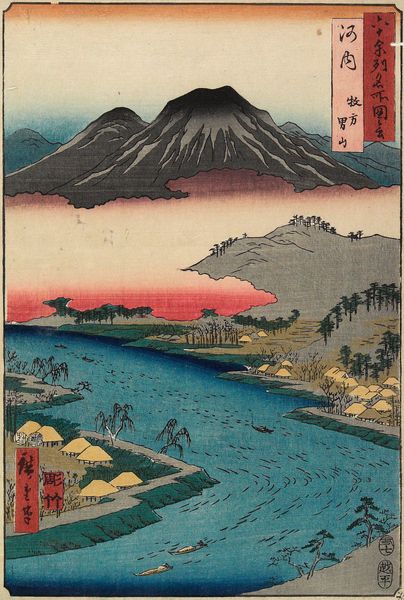

print, ink, woodblock-print

#

water colours

# print

#

asian-art

#

landscape

#

ukiyo-e

#

ink

#

woodblock-print

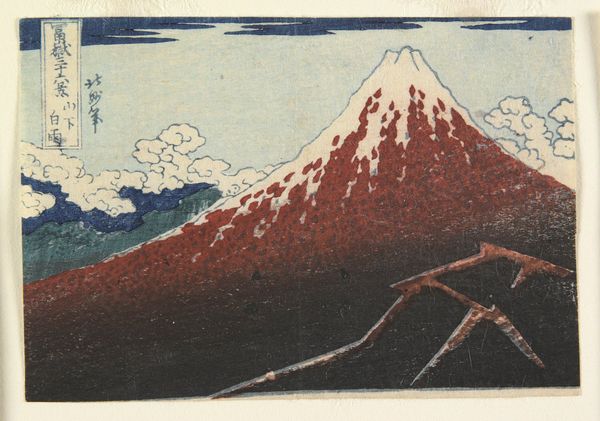

Dimensions: 3 1/8 × 4 5/8 in. (7.9 × 11.8 cm) (image, sheet, yatsugiriban)

Copyright: Public Domain

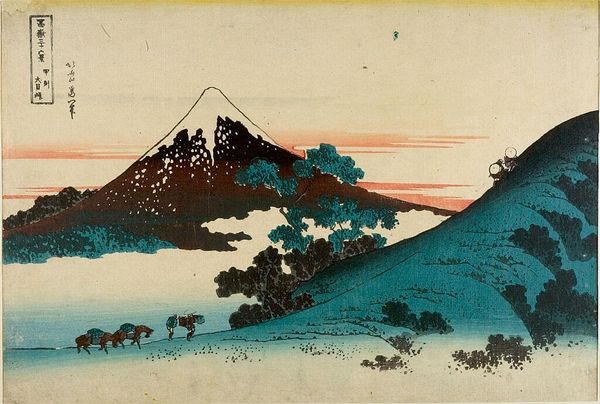

Curator: Well, look at this gem! "South Wind," a woodblock print crafted between 1834 and 1837 by Hokumyō. It resides here at the Minneapolis Institute of Art. I feel this… well, a very soft happiness when I gaze at it, almost meditative. What's your read on this little landscape, my friend? Editor: Meditative is a great way to put it. What strikes me immediately is its placidity—though, as we know, such idealized landscapes can belie more complex social realities. How was access to this scenery structured by class, gender, and even national identity? Curator: Absolutely. This serenity—did it extend to all who might've glanced up at the majestic mountain? These prints, Ukiyo-e as they are called, became increasingly accessible, though social hierarchies always linger, even in art meant for the masses. The mountain seems powerful, and yet very still. Editor: And that stillness is deliberately constructed. Landscape painting wasn't merely about replicating scenery; it was also about reinforcing ideas of nationhood and cultural identity, about creating shared narratives. We can look into issues regarding the representation and the political connotations that this entails. Curator: Interesting points. While that coral peak of Mount Fuji takes the forefront here, do you think, even in its muted tones, this coloration makes this image such an appealing example of the *fūkei-ga* landscape print genre? It's simple, but the execution isn't—look at the gradation. Editor: Indeed, this vibrant gradient that characterizes *South Wind* is not by chance but through a calculated effort for the sake of idealizing an orientalist and masculine nation. It suggests also a link between state and aesthetics that one needs to study to avoid repeating present-day state impositions and other impositions of culture through politics and war. Curator: Right, right! Perhaps Hokumyō aimed for some grand patriotic statement—or maybe a quiet ode to a mountain, so beloved and so powerful, so deeply integrated with a common national psyche? Perhaps all that analysis is, quite simply, our projecting voices from the 21st century! Editor: The dialogue across centuries is never without risk of anachronism, is it? Even still, this particular perspective invites contemplation on the enduring human quest for national ideals. What makes a place sacred, for whom, and at what cost? It is, in itself, an eternal landscape. Curator: Hmm, yes... Eternal... Okay, but it is getting a bit intense now. As a painter, let me ask this—have you tried replicating that shade of red in watercolor? The nuance! It’s otherworldly. Well, thanks for shedding new light to our understanding of it. Editor: And likewise! Context does allow new perception of artworks, or art in general!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.