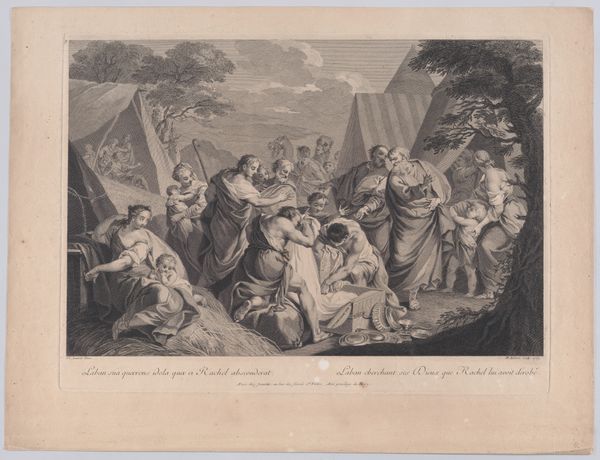

print, paper, engraving

#

narrative-art

# print

#

paper

#

history-painting

#

academic-art

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 313 mm, width 402 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

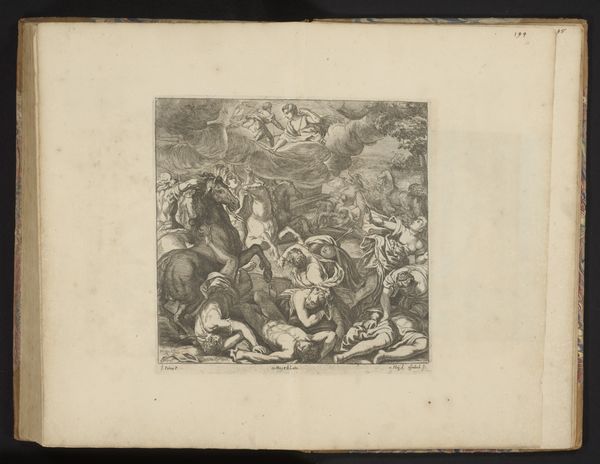

Curator: Let’s turn our attention now to "Dood van generaal Wolfe, 1759," or "The Death of General Wolfe, 1759," a print made sometime between 1818 and 1886. This engraving on paper is attributed to Friedrich Randel. Editor: Wow, what a scene! It's like a perfectly staged tableau, full of drama and quiet solemnity. I feel like I’ve stumbled onto a stage production. Everything is so meticulously rendered, so deliberately… theatrical? Curator: Exactly! It is crucial to consider the history of history painting here. Randel, working in the academic tradition, depicts a pivotal moment from the Battle of Quebec. This work carries echoes of Benjamin West's famous painting of the same subject, setting a stage for exploring power, sacrifice, and imperial narratives. Note how the image romanticizes death. Editor: The way the figures are clustered around Wolfe – it almost feels like a Renaissance deposition scene, but in colonial garb. And look at the Indigenous figure contemplating the scene, adding another layer of complexity and, dare I say, discomfort. What is his story here? I bet he's not on board with the British project. Curator: Your reading of discomfort is astute. The "noble savage" trope is evident, framing Indigenous people in relation to European conquest. This artwork doesn’t only record a moment of death; it also produces meaning about the victor, the vanquished, and the cost of empire. By understanding those themes, we unpack these ideological components. Editor: It all feels very... curated, if you know what I mean. Even the chaos of battle seems to have been tamed and neatly packaged for consumption. I find it fascinating, how history can be so carefully constructed – and endlessly reinterpreted. It reminds me that even the "truth" has many faces and that these black and white values shift constantly. Curator: Precisely. Randel’s engraving invites critical reflection on how historical narratives are constructed and consumed, then and now. Its impact lies in its ability to spur discussions of identity, power, and representation across centuries. Editor: I love the questions that linger! The details, though meticulous, point to larger unresolved narratives and, if we stay a little longer, we realize how relevant those silences are.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.