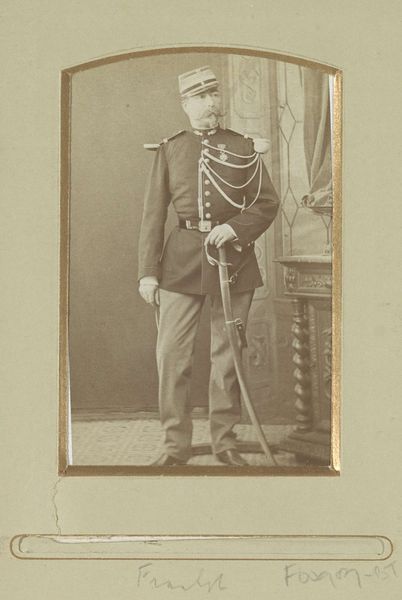

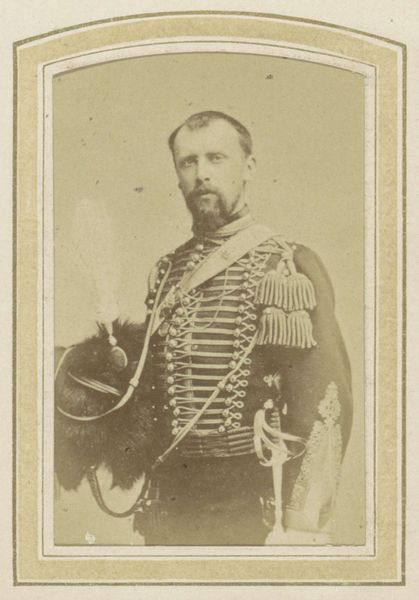

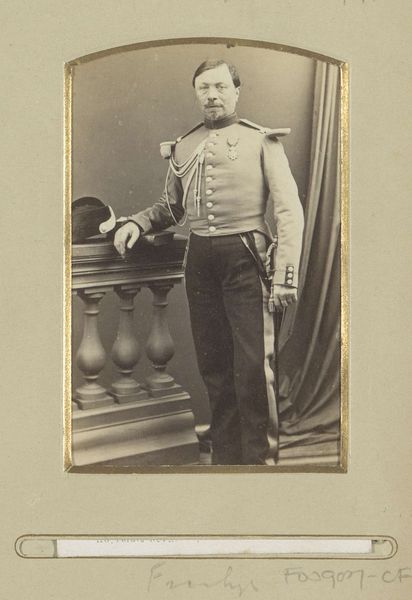

Studioportret van Generaal-Majoor G.B.T. Wiggers van Kerchem met onder andere zijn Militaire Willemsorde 1875 - 1895

0:00

0:00

woodburypage

Rijksmuseum

photography, albumen-print

#

portrait

#

archive photography

#

photography

#

historical photography

#

19th century

#

albumen-print

Dimensions: height 136 mm, width 100 mm, height 165 mm, width 109 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This is a studio portrait of Major General G.B.T. Wiggers van Kerchem, decorated with, among other things, his Military Order of William. The photograph was taken sometime between 1875 and 1895 by Woodbury & Page in Batavia, Java. It’s an albumen print. Editor: The sheer density of the medals and braiding is what strikes me first. It feels almost performative, this weight of regalia… I can almost smell the starch in the uniform! Curator: Absolutely. These photographs served a specific purpose, constructing an image of power and colonial authority. Consider the photographers, Woodbury & Page: their studio mass-produced these images for a European audience eager to consume visuals of Dutch colonial enterprise. Editor: Mass production via albumen prints. The chemical process itself is fascinating—egg whites used to bind the image to the paper. Talk about materiality shaping meaning! It reminds me how images were made and disseminated; a very physical and laborious process that influenced circulation and reach. Curator: Precisely. And it’s interesting to consider the general’s pose; one hand resting on his helmet, the other on his sword. It speaks volumes about the performance of masculinity and military prowess expected of leaders in the colonial context. Look closely. Every button, every tassel is meticulously rendered. Editor: True, but think about the labor involved. Each print required careful preparation and printing, highlighting a structured hierarchy of labour from production to commissioning. What survives in museum storage conceals an almost forgotten manufacturing system. Curator: It prompts questions about what aspects of our colonial past are elevated into prominence through such photographs, and equally, which aspects are actively erased and made invisible through the photographic process? Editor: Looking closer has made me reconsider the colonial machinery, its systems of representation and manufacturing, and what all that meant for Java, as the production site, rather than a consumption center. Curator: Exactly. Examining it in this light challenges conventional assumptions about how we engage with this photograph today, urging us to question power structures inherent in historical documentation. Editor: Well, thinking about its production has broadened the colonial narrative, for me. Now I have the urge to go research what remains from the production site where it was manufactured.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.